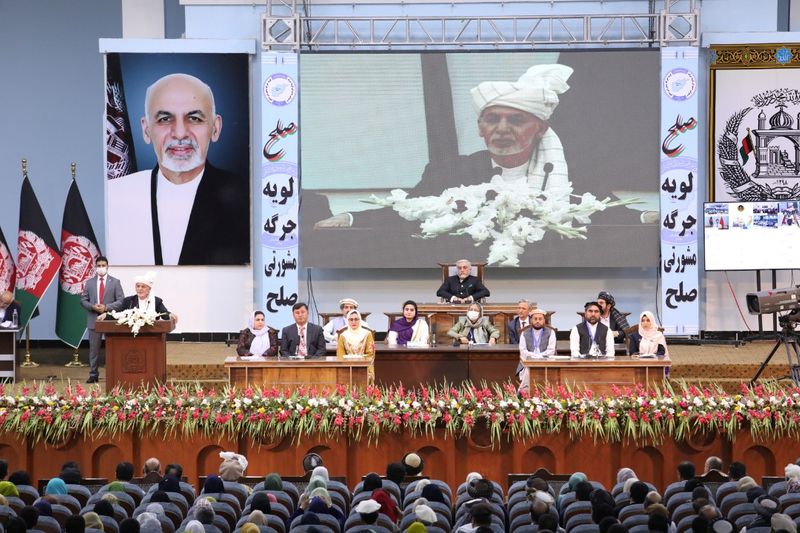

KABUL (Reuters) – Thousands of Afghan elders, community leaders and politicians gathered on Friday to debate whether the government should release 400 hard-core Taliban prisoners, a move that would likely quickly clear the path for peace talks.

Some 3,200 people have been invited to the grand assembly, known as a Loya Jirga, in Kabul amid tight security and the coronavirus pandemic, to debate for at least three days and then advise the government on whether the prisoners should be freed.

President Ashraf Ghani addressed the meeting as it opened, saying that the Taliban had said once the 400 prisoners were released they would start negotiations within three days and commit to a ceasefire.

The Taliban did not immediately respond to a request for confirmation of this.

As part of a February pact between the United States and the Taliban allowing for the withdrawal of U.S. troops, it was agreed that some 5,000 Taliban prisoners should be released from Afghan jails as a condition for talks between the militants and the U.S.-backed government.

The government has released all but some 400 militants it says have been involved in some of the worst crimes including major attacks such as the 2017 truck bombing near the Germany Embassy in Kabul.

Six Loya Jirga committee leaders and members told Reuters that based on preliminary conversations they expected the majority to vote in favour of freeing the prisoners, though they would only be able to confirm that after the meetings took place.

“If releasing 400 would result in stopping bloodshed, then so be it,” said a Jirga member who heads one of the committees.

The three-day Loya Jirga has the power to advise the government but its decision is not binding.

CONCERNS ABOUT THE TALIBAN

While many Afghans see the peace effort as the best hope for ending the 19-year war with the Taliban, some question how committed the militants are to reconciliation, especially after the United States completes its troop withdrawal.

Washington has been urgently trying to ease the deadlock over prisoners as it withdraws troops and President Donald Trump seeks to fulfil a major campaign promise to end the war in Afghanistan.

“The U.S. wants peace talks to begin as soon as possible, so it doesn’t have to deal with the bad optics of withdrawing forces while the war is still raging with no end in sight,” said Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Program at the Wilson Center.

“For Ghani, the advantage of a Jirga is that he can’t be fully blamed for whatever decision is made, given that it would reflect a wide consensus.”

Abdullah Abdullah, a former presidential candidate, was appointed the new head of the Loya Jirga on Friday. A post-election feud between him and Ghani, resolved in May, contributed to delays getting the peace talks going.

(Reporting by Hamid Shalizi; Additional reporting by Charlotte Greenfield and Abdul Qadir Sediqi; Writing by Hamid Shalizi and Charlotte Greenfield; Editing by Robert Birsel and Frances Kerry)