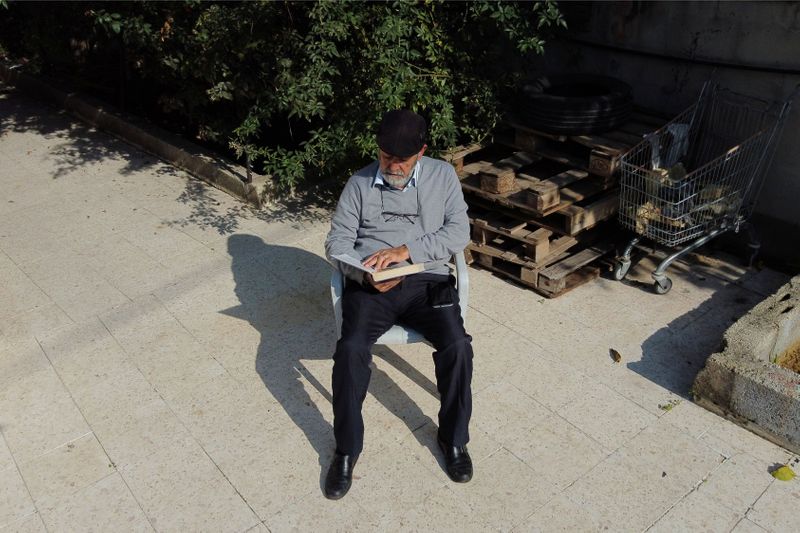

JERUSALEM (Reuters) – For Nabil al-Kurd, being forced out of the East Jerusalem home he has lived in since the 1950s would be a fate worse than death.

But the 76-year-old and his wife and children are among dozens of Palestinians under threat of eviction from two districts of the disputed city, after an Israeli court ruled their properties are built on land belonging to Jewish settlers.

“This is my motherland. All my memories are in this house,” Kurd told Reuters. “I won’t leave unless it is to the cemetery.”

The ownership claims against him and others in Sheikh Jarrah and a second neighbourhood, Batan al-Hawa, are a focal point of settler development plans in East Jerusalem, captured by Israel in a war in 1967.

Kurd was ordered evicted in October, within 30 days.

He has appealed to the Jerusalem District court, though Hagit Ofran, project coordinator for Israeli anti-settlement group Peace Now, says he has little chance of overturning the ruling.

That same court has this year upheld several settler claims, based on 19th- and early 20th-century documents, drawing censure from the European Union, whose representative in Jerusalem says 77 Palestinians are at risk of forced transfer.

CITY AT THE HEART OF CONFLICT

The status of Jerusalem, a city holy to Jews, Muslims and Christians, is at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Palestinians want the capital of their would-be state to be East Jerusalem, and most countries regard settlements that Israel has built there as illegal.

Israel disputes this, citing biblical and historical links to the territory, as well as security needs and legal arguments.

Many of the Palestinians facing eviction were refugees like Kurd or their descendants, who came to the area more than half a century ago, Peace Now said.

The settlers in Kurd’s case bought the land from two Jewish associations that claimed to have purchased it at the end of the 19th century, the group said.

A lawyer who represented the settlers claiming Kurd’s property declined to speak with Reuters.

Peace Now says some 14 families have been evicted from Batan al-Hawa since 2015 and 16 from Sheikh Jarrah since the late 1990s in such cases.

Evictions are typically stayed while appeals are heard, and some of the residents have appealed their cases to Israel’s Supreme Court, but Kurd’s family is taking no chances.

“My family has prepared luggage of the important things we need so that if they come in any second, we will be ready,” said daughter Muna al-Kurd.

“…We have a camera at the house, four cameras that show the street, and dad stays up until two to three in the morning just watching if they are coming to evacuate us.”

(Writing by Rami Ayyub; Editing by Jeffrey Heller and John Stonestreet)