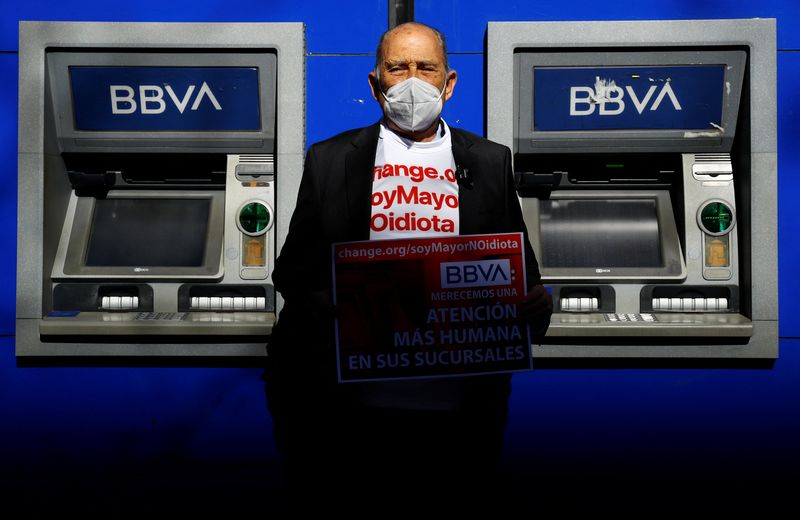

MADRID (Reuters) – Aggravated by fiddly financial apps, retired urologist Carlos San Juan got more than he bargained for when he began a campaign for a more user-friendly service from Spain’s banks.

The 78-year-old kicked off a revolt dubbed ‘I’m old, not an idiot’ online at the end of December and by mid-February had more than 640,000 signatures, forcing a change of tack.

Now Madrid has given Spanish banks until the end of the month to address the needs of the elderly, with services such as withdrawing money from ATMs or being able to operate remotely.

“I’m asking that they treat their customers from whom they make money with humanity and courtesy, no matter how old they are,” San Juan told Reuters.

Among Spain’s more than 9 million over-65s, who represent almost 20% of the total population, many have struggled to manage their finances since bank branches started vanishing from the high street.

The problems lay bare the disconnect between pursuing profits through massive layoffs and servicing the needs of a section of the population struggling with cheaper channels.

San Juan says urgent measures such as a face-to-face customer service throughout office hours were among the priorities, before embarking on financial education.

Despite more than halving the number of branches since the financial crisis in 2008, Spain still has one of the densest banking networks in the world, with slightly more than 45.5 outlets per 100,000 adults.

“It’s not a problem about a lack of branches, it’s about banks not assisting (the) elderly properly,” Patricia Suarez, head of Spanish consumer association Asufin said.

San Juan’s campaign has now spread to Germany, where close to 30% of the 83 million people are 60 or older.

Nicola Roehricht of the German National Association of Senior Citizens’ Organisations is on a similar mission.

Roehricht travels the country, speaking to policymakers at conferences and senior citizens in their homes about the importance of making cyberspace more inclusive.

“We tell seniors, ‘Ask the banks to help you with banking’ We mustn’t be ashamed that we have a smartphone and we don’t know how it works. You must show up and say, ‘I don’t understand your strange English expressions. So help me’,” she said.

EXCLUSION

While traditional banks in Spain, such as Caixabank, have cut thousands of jobs to cope with ultra low interest rates, those with a pure digital approach have been able to better cope with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Spanish and Portuguese unit of Dutch bank ING, this week said it had increased its return on equity (ROE) to 12% at the end of 2021 compared to 7.4% a year ago. That compares to an average ratio of 6.9% in Spanish banking.

The ING unit said that its cost of managing deposits, loans and investment products was roughly a third lower than the Spanish average as it has just 1,400 employees in Iberia.

In digital-laggard Italy, the elderly can still find all the help they need in a branch but as banks close outlets, problems are looming FABI union leader Lando Maria Sileoni said.

Italy’s biggest bank Intesa Sanpaolo, which plans to cut 22% of its branches in the next four years, has struck a partnership to provide basic services such as bill payments through 45,000 cafes and tobacconist kiosks.

And in Britain, the government plans legislation to ensure that the digital banking drive does not cut older people adrift.

COMPLEX

In Spain, AEB banking association head Jose Maria Roldan recently thanked San Juan for highlighting a “problem that was much more complex and more permanent than we thought”.

Jose Ignacio Goirigolzarri, chairman of Spain’s biggest bank by domestic assets, said that a quarter of Caixabank clients over 70 used remote channels compared to 85% in their thirties.

A draft document seen by Reuters from joint voluntary proposals shows Spanish banks plans to extend over-the-counter services, dedicate staff to engage with the elderly and make apps more user-friendly.

Other senior Spanish bankers, including BBVA chairman Carlos Torres, say that technological exclusion does not only affect older people but is an issue of “digital skills”.

Santander, BBVA, Sabadell and smaller lender Abanca have recently announced they will extend or have already extended cashier services in their networks.

But none plan to hire any extra staff, something that Asufin and Comisiones Obreras, Spain’s biggest union in the sector, say may increase the workload of overstretched employees.

Antonio Luque Delgado, a banking employee for more than 25 years, said that hiring would be key to address this, especially after banks have cut 100,000 jobs since the financial crisis.

“When you force a 70-year-old person to download an app, you know that it is not going to work. You know that the customer will be back in the office the next day because he has forgotten the password, because he has entered it wrongly,” Luque said.

For San Juan, the battle for inclusion is just beginning.

“This is not the end. Good causes fail because of fatigue, we will go on,” he said.

(Reporting by Jesús Aguado; additional reporting by Tom Sims in Frankfurt, Valentina Za in Milan and Iain Whiters in London; editing by Alexander Smith)