Shannon Hoon, the lead singer of Blind Melon, routinely filmed himself from 1990 to 1995. The footage captures the sum trajectory of Hoon’s career. It begins with his roots in rural Indiana, follows his move to Los Angeles, where he forms Blind Melon, and watches their stars rise as they become emblematic figures of music video culture. All the while, Hoon navigates the trappings of substance abuse, which ultimately took his life. The film begins and ends with footage that Hoon captured on the day that he died of an overdose.

Danny Clinch, Taryn Gould and Colleen Hennessy, the film’s directors, elected to not present the material accompanied by the typical crutch of talking heads. This is not a typical rock documentary. The film is entirely shot by Hoon and seen from his effusive and endearing perspective and has an absorbing abstract tone. It’s clear the group cared deeply about Hoon and presented this deftly edited and extremely personal footage in mind of Hoon’s life’s truth. Clinch “cut his teeth” as a music photographer with Blind Melon and they were the first to offer him unfettered access. “It meant so much to me and I wanted to honor the band and the people who contributed to it,” Clinch said.

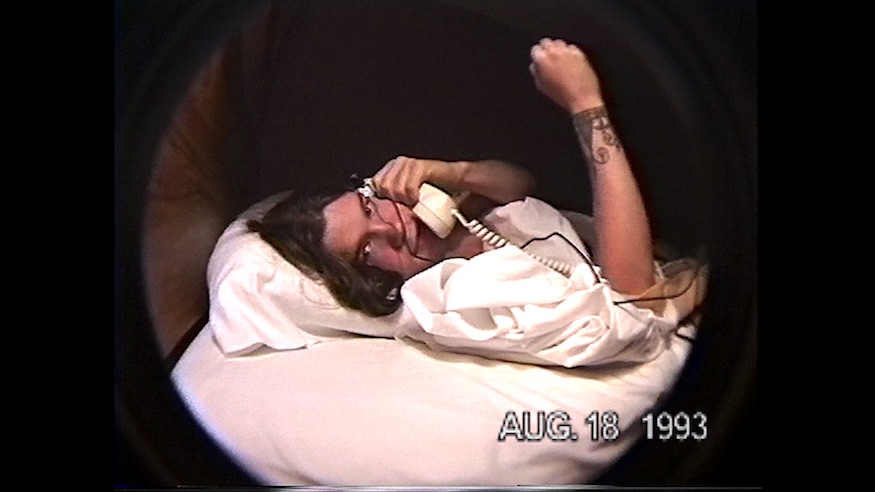

Backstage hangouts and footage of the band performing are interspersed with experimental footage. “Being impressionistic and artful in some of these sequences was really important to us and it was clear Shannon was with us,” Clinch said. The film serves as a union of Hoon’s life and his art, and we watch Hoon develop this aesthetic while we watch his life change. “He was videotaping himself before he was famous, until the day he actually died,” said Clinch. The dawn of a self-documenting generation begins as a member of the band posits, “You can get your whole life on video now. No one before us could do that.”

Additional footage paints the backdrop of 1990s culture — Hoon films the television as it shows the Rodney King riots and the announcements of the deaths of Jerry Garcia and Kurt Cobain. The memory surfaces that people who had a high profile were still inaccessible back then. Hoon hangs out backstage with Slash and Axl Rose shortly after he moves to L.A. and nobody is taking selfies with anyone.

“Shannon was unafraid and would film anything in any way,” Clinch said.

Things take a turn as Blind Melon progress from L.A. outsiders to MTV stalwarts with the song “No Rain” and its music video that explodes in popularity, raising the band’s profile in turn. As their artistic lives immediately become more commodifiable, the realities of fame and expectation begin to weigh on Hoon. “When you have a hit like ‘No Rain,’ it becomes a blessing and a curse. Every journalist they meet and every fan and everyone is talking the same thing and they’re talking about the bee girl and the video and that stuff gets overwhelming after a while,” Clinch says.

The film is a thoroughly thought-provoking and meditative take on mortality and the nature of artistic ambitions. The audience knows from the very beginning that Hoon will die, and precisely when. This foreknowledge gives a unique inside view on temporality and the unimagined consequences of realizing your ambitions. Hoon mentions wanting to work more in film and develop himself further creatively, and all the while, we can see from the date in the bottom-right corner that he only has a finite number of days left in his life.

The filmmakers wisely employ no voices or narrator telling you what parts of Hoon’s life are important or what they think you should know. Hoon’s life is presented just as he saw it, and the audience is left to look and listen in wonder at something only as it really was.