There are only a few jobs that can defy the laws of life and death. Transplant surgeons have the unique ability to take an organ or an appendage and have it come back to life after attaching it to a patient in need. We spoke with Joshua D. Mezrich, M.D., the author of “When Death Becomes Life: Notes from a Transplant Surgeon,” about why got into the field and some of the unexpected things that have come with the job.

An inside look at life as a transplant surgeon

Photo: Provided

What made you want to become a transplant surgeon?

When I was growing up, my dad went back to medical school when I was in third grade. He would always kind of tell stories from med school at the dinner table. I think my brothers were sort of grossed out, but I loved them. That was one piece. Of course, I always loved Hawkeye Pierce from “M.A.S.H.”! As I went through college, I took the sciences on the side. I majored in Russian but I didn’t think I’d go into something with Russian as a career. I took all of the premeds on the side and always remained interested in science and medicine. When I entered med school, I didn’t know anything about surgery and I never would have thought in a million years I’d go into surgery or transplant. But, I ended up loving my surgical rotation!

This almost sounds cliche, but it’s a true story. My first day on surgery, I went in at like 5 a.m. I was just a crazy day. I found out I was on call which was a perfect preparation for my future life. I didn’t eat or drink anything and I was in the O.R. all day. Then finally at midnight, my resident told me to go next door to this operation. When I went in, it turned out it was a kidney transplant. This older surgeon was doing the transplant. He had classical music playing and it was really calm and relaxed. When we reperfused the kidney and it turned pink in front of my eyes and urine just started spraying out on to my hands, I was just staring at it thinking, “I can’t believe this works!”

I wondered what other organs can we do this for and could I ever do this? I was really intrigued by the challenge and the mystery of it. I was very aware that someone had just died and this organ was coming back to life. It just struck me as truly remarkable.

In the book, you talk about how people are your puzzles. Is there a sense of gratification or panic in solving such a complex problem?

I try not to panic! I like to use the word “gratification” or the word I often use is “satisfying”. I think surgery is too hard to be fun, but it is incredibly satisfying. I think everything about surgery is your brain. It’s making good decisions and solving the puzzle. Some puzzles are simple with 50 pieces and some puzzles are a bit complex with hundreds or a thousand pieces. When it comes to doing operation, it really is about thinking through the puzzle, taking what the case gives you, and really focusing hard on what it is you’re looking at. And if something doesn’t look right, stepping back and rethinking it. It does involve a lot of pre-planning, but I’ll take a good brain over a good set of hands any day of the week when it comes to looking for a surgeon.

I really do look at it like a puzzle. Lots of practice helps. Experience is critical but you just have to watch the signs and stay focused and try to stay positive. When things start going badly you have to find a way to stay strong and not panic. It kind of gets easier in the sense that you get more experienced, but it gets more humbling to because no matter how many years you have in you always find cases that are really challenging. When I’m operating, I’m not sitting there thinking, “Oh my god. This person has kids!” [laughs] You really are focused on solving that puzzle and doing it in the simplest way you can.

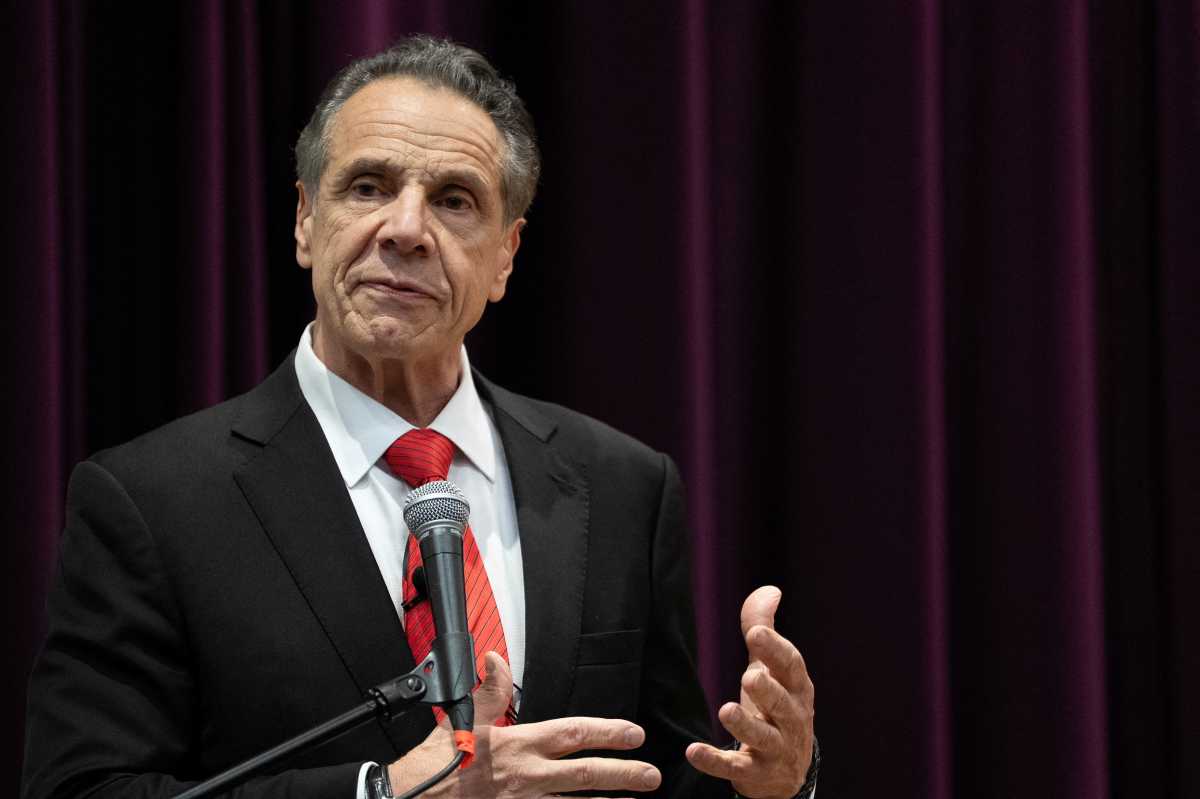

Joshua D. Mezrich.Photo: John Maniaci

What are some of the most surprising aspects of the job?

To me, some of the most beautiful stuff has been my interactions with both the deceased donors families and the living donors. To me, it is so heroic and it’s kind of like running into a burning building to save someone. On the deceased donors side, we fly out and get the organs, which is something most people don’t realize. We meet with the donor families and when I first met my first family I thought it was going to be this uncomfortable experience because I’m this vulture coming to take apart their loved one. But that couldn’t have been further from the truth. Usually there’s a big group of people there. They’re crying because they just lost this loved one, maybe unexpectedly. Yet, they hang on to every one of our words. They want to know what we’re going to do. It ends up being this incredibly positive experience. It’s a really incredible feeling. It makes you realize that this is a gift and our job is to make sure that the gift is given.

The living donors are some of the most incredible people you could meet. But, I think one of the real beauties of this is that in most illnesses the patient is really kind of suffering alone. While they’ll have family around, the patient goes through it alone. The patient endures it alone, they take the tests alone, and ultimately, they can die alone. But in transplant, there is this opportunity for someone to step forward to say, “Let me bare this with you and take a little pain to help you get through this.” I just think there is something really special about that. Being a part of that exchange is really one of the most gratifying parts about being in my field.