(This Jan. 14 story refiles to correct analyst’s first name to “Naz” in paragraph 18)

BERLIN (Reuters) – The conservative leader favoured by German voters isn’t even running in this week’s contest to head up Angela Merkel’s party, but he aims to play a pivotal role in determining its candidate to succeed her as chancellor, party sources say.

He may even take on that role himself if the eventual winner of the imminent party vote to replace her flops, according to the sources inside the governing conservative alliance.

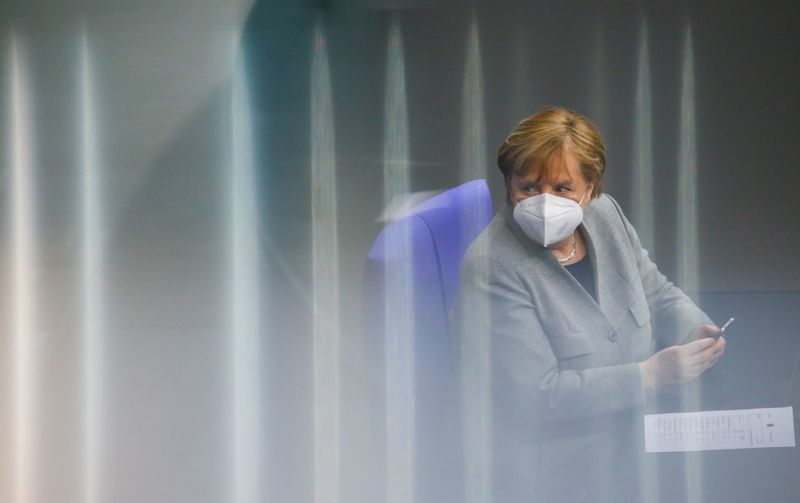

Merkel, who steps down after federal elections in September, is heading into the last months of her tenure with her Christian Democratic Union (CDU) squabbling over how to position the party following 15 years of rule marked by her instinct to compromise.

The CDU elects a new chairman on Saturday, but none of the three contenders impresses voters, leaving the party wondering how best to replace Merkel, a proven election winner who has become Europe’s predominant leader since taking office in 2005.

Centrist Armin Laschet, arch-conservative Friedrich Merz and foreign policy expert Norbert Roettgen are battling it out.

Merkel said last year Laschet, 59, had “the tools” to lead Europe’s biggest economy and most populous country, but voters find him uninspiring.

Enter Markus Soeder. The burly, confident leader of the CDU’s Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), is voters’ choice conservative. He senses a unique chance to assert himself as a unifier, or else as chancellor candidate.

“Soeder will either play the role of king, or of kingmaker,” a CDU Executive Committee member told Reuters.

The three declared CDU candidates all differ from Merkel.

Roettgen, 55, the eloquent chairman of parliament’s foreign affairs committee, wants Germany to take a firmer stance with Russia and China. Merz, 65, has targeted European Central Bank policy and is less diplomatic. Laschet, who has polished his international profile, complains Berlin has taken “too long to react” to French calls for European Union reform.

Soeder, 54, Bavaria’s premier, is a political chameleon who has shifted from the right towards the moderate centre of late, though remains an unknown on foreign policy.

He plays coy about his ambitions – “My place is in Bavaria” has been his repeated refrain.

But the Bavarian’s lieutenants are already manoeuvring for the CDU/CSU alliance, the “Union”, to pick the chancellor candidate most likely to win September’s election, rather than simply default to the CDU party leader, as is traditional.

“A personnel decision will have to be based on this (criteria), regardless of who becomes the new CDU leader on Jan. 16,” Alexander Dobrindt, the CSU’s leader in the Bundestag (lower house of parliament), told a CSU gathering last week.

BAVARIAN SWAGGER

Whether Soeder decides to run for chancellor, or simply plays a role in determining who will, his swagger promises to embolden conservatives tired of Merkel’s centrist compromises – even if he cannot match her pedigree on foreign affairs.

After making his mark with a barnstorming speech at the CDU’s 2019 congress, Soeder has cosied up to the environmentalist Greens – the Union’s likely next coalition partner – and presented himself as a strong manager of the coronaries pandemic at regular news conferences alongside Merkel at which he has represented Germany’s states.

He also projects charm that appeals to Germans beyond his native Bavaria.

“Soeder is a very savvy politician, but rather a novice when it comes to EU affairs and international politics,” said Naz Masraff, analyst at the Eurasia Group consultancy.

To be sure, no German chancellor has ever come from the CSU, although Franz Josef Strauss and Edmund Stoiber of the CSU were the Union candidates in the 1980 and 2002 federal elections, respectively, which were both won by the Social Democrats.

This time though, Soeder’s hand is strengthened by deep divisions between the three CDU men – all from the western state of North Rhine-Westphalia – coveting the votes of 1,001 party delegates who will pick a winner at Saturday’s digital meeting.

Laschet and Roettgen’s supporters aim to stop Merz, who wants to shift the CDU to the right. Last year, Merz stoked party divisions by saying elements of the CDU establishment didn’t want him to get the job.

A survey by pollster Civey for newsmagazine Der Spiegel late last month showed that if all Germans could vote, Roettgen, who is pitching himself as a moderniser, would be the CDU chairman and Soeder chancellor.

Roettgen has hinted at such a possibility. Last September, he said a CDU leader must “be humble enough to do what is best for the party”.

The Spiegel poll showed voters favoured Roettgen for the CDU leadership, with 31.7% support, followed by Merz on 28.8% and Laschet on 11.8%. However, Laschet controls the CDU in North Rhine-Westphalia, which provides 298 of the 1,001 delegates.

Ahead of the CDU congress, senior conservatives Ralph Brinkhaus and Wolfgang Schaeuble have both said the chancellor candidate does not have to be the new CDU chief – potentially opening the way for popular Health Minister Jens Spahn.

Asked on Wednesday whether he would run as a candidate for chancellor, Spahn, who is backing Laschet for party chairman, told Deutschlandfunk radio: “As of today, I rule that out.”

Soeder has also signalled his support for Laschet, praising his experience and coalition-building abilities.

Serap Gueler, a CDU delegate and Laschet ally who plans to vote for him, called him “a man of conviction” but added: “I think his weakness is maybe … that he tries to explain certain things to the last comma, and that can make them complicated.”

Soeder wants to give the new CDU leader time to win over voters and, with his help, unite the party – or else unravel. He has called for the Union to decide on its chancellor candidate only after state elections in mid-March.

“If he feels that the CDU leader has a real chance, he will tend to play the kingmaker,” said senior CSU lawmaker Hans Michelbach. “But if he concludes the CDU leader doesn’t cut it, then things are different.”

(Writing by Paul Carrel; Editing by Mark Heinrich)