BUENOS AIRES (Reuters) – Meltwater could undermine the walls of ice holding back Antarctica’s glaciers, scientists reported on Wednesday, a finding that underscores concern about the potential for a significant sea level rise.

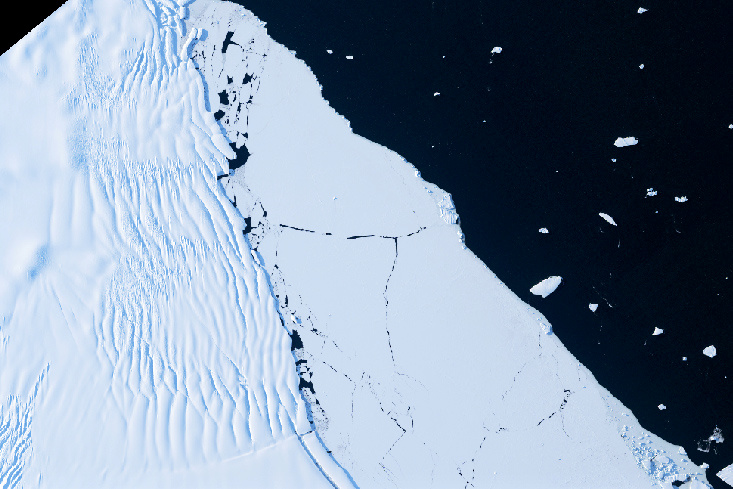

The ice shelves, formed over thousands of years, serve as dams to prevent much of the continent’s snow and ice from flowing toward the ocean.

Scientists found that about 60% of the ice shelf area is vulnerable to a process call hydrofracturing, in which meltwater seeps into the shelves’ crevasses, some of which are hundreds of meters deep, and triggers collapse.

“This meltwater is heavier than ice, so it can penetrate through the entire ice thickness, just like a knife,” said climate scientist Ching-Yao Lai at Colombia University.

It’s unclear how long such a process might take. Antarctic weather is highly variable, making it difficult for scientists to determine how much of a role is being played by human-caused climate change.

Lai said, however, that previous research suggested meltwater could cover the ice shelves in about a century.

The new study, published in the journal Nature, used AI to identify ice-fracture features in nearly 260 satellite images of 50 ice shelves across the continent. Those ice shelves surround about 75% of the Antarctic coastline.

Finding vulnerabilities in the ice shelves buttressing the glaciers above was a surprise, Lai said.

“Previously, we thought there are going to be places vulnerable to hydrofracture, but that those places might not matter at all for the ice sheet,” Lai said.

Scientists fear that losing ice shelves to hydrofracturing will leave Antarctica’s ice sheets, which are as big as the United States and Mexico combined, a more direct pathway to the ocean. That could accelerate ice loss and contribute to sea level rise.

The latest reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change project that future sea levels will rise by more than a meter by 2100. However, scientists worry that a sudden collapse of these steep ice shelves could raise future sea levels dramatically. More than half of the world’s fresh water is locked into Antarctica’s ice.

Meanwhile, warming temperatures driven by climate change are also eating into glaciers and the ice sheet in the Arctic. Last month, Canada’s last intact ice shelf collapsed.

And Greenland’s ice sheet lost a record amount of mass last year, raising concerns the icy bulk is melting more quickly than anticipated. Greenland’s ancient ice sheet holds enough water to raise sea levels by at least 20 feet (6 meters) if it were to melt entirely.

In Antarctica, if “we start seeing the collapse of some of this ice that is there like a wall holding back everything behind it, it’s just going to accelerate the pace of sea level rise beyond what we’re probably predicting right now,” said Alexandra Isern, head of Antarctic studies for the U.S. National Science Foundation who was not involved in the study.

Once gone, the ice shelves wouldn’t be able to form again “in any time we’ll ever see,” Isern said. “It took a long time to make them, and it maybe isn’t going to take as long to get rid of them.”

Scientists say that, while governments should prepare for higher seas, there is still time to curb climate-warming emissions in order to slow the rate of sea level rise and avoid coastal catastrophes.

“There’s no ice on the planet that gets along well with warming air and warming ocean temperatures,” said glaciologist Twila Moon at the National Snow and Ice Data Center who was not involved in the study.

“These kinds of details and tools are helping us to narrow our range of being able to say what will happen in the future, given that humans follow any particular path.”

(Reporting by Cassandra Garrison in Buenos Aires and Marc Jones in London; Editing by Katy Daigle and Bernadette Baum)