GOLD RIVER, Calif. (Reuters) – During a typical spring, the silver young salmon swimming in long tanks at the Nimbus Fish Hatchery east of Sacramento would be released into the American River and then make their way out to the Pacific Ocean to grow to adulthood.

But with extreme drought now gripping California and much of West Coast, the rivers are too warm for the salmon to survive.

This week, the 3.5-inch (90-mm) smolt, as the young fish are known, embarked on a much different journey when they were loaded on to trucks and driven to the San Francisco Bay for release into cooler waters.

Low amounts of rain and snow led to less water and warmer temperatures in the state’s rivers and reservoirs, said Jason Julienne, who manages several state-run hatcheries in the Sacramento River system, including the Nimbus.

When those conditions occur, “we know we have to really go into high gear to make sure these fish survive,” said Harry Morse, spokesman for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The state plans to truck 17 million of the smolt to the San Francisco Bay this year from various hatcheries, an emergency step not taken since the last major drought in 2014, Morse said.

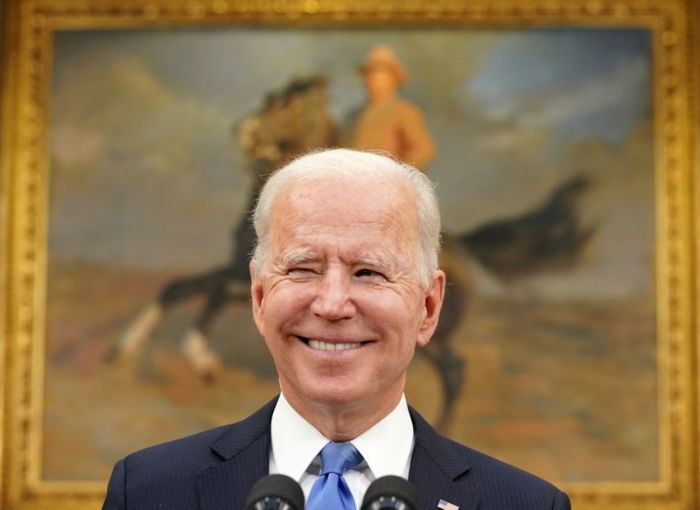

On Monday, California Governor Gavin Newsom declared a drought emergency for 41 of the state’s 58 counties, including the major watersheds relied on by salmon and other wildlife.

Droughts in California are growing more frequent and more intense as climate change continues, threatening the state’s already tenuous supply of water for wildlife, farmers and urban areas, and creating conditions ripe for dangerous wildfires.

Other portions of the West Coast are also experiencing severe drought. In Oregon, federal officials said on Wednesday that a portion of water from the Klamath River system would not be available to farmers, and that additional protections for salmon and other fish were under consideration.

Even without drought and climate change, salmon and other fish were struggling to survive on the West Coast, as water projects such as dams and reservoirs inhibit their ability to migrate to the sea and back, a natural part of their life cycle that can take about three years.

Two species of Chinook salmon are considered endangered on the West Coast, and seven are considered threatened under the Endangered Species Act, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In the American River in California where the Nimbus smolt are usually released, water from rain and snow was flowing at just 31% of its average rate on Tuesday, according to state data. The resulting warmer water has created a desperate situation not only for the fish at the hatchery, but for the hundreds of thousands of fry and eggs laid naturally in the rivers themselves.

“My biggest fear is that each and every egg that is laid this year is going to die because the temperatures in the rivers are going to be too high,” said Mike Conroy, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations.

His organization is asking the state and federal agencies that apportion water from a complex system of reservoirs to make sure that sufficient cool water is released to prevent the rivers from becoming toxic to young fish, Conroy said.

But others – including a California agricultural sector that produces a third of the country’s vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts – also rely on that water. As more water is reserved for fish, less is available to irrigate farms and for the state’s 40 million residents.

“The pull of one wrong lever can throw the whole system out of whack,” said Conroy. “It has to be carefully balanced.”

(Reporting by Sharon Bernstein; Editing by Colleen Jenkins and Lisa Shumaker)