BERLIN (Reuters) – Germany has been forced to cancel public events to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of World War Two in Europe but Berliners need no ceremonies to remember their downfall – the scars of war are all around them.

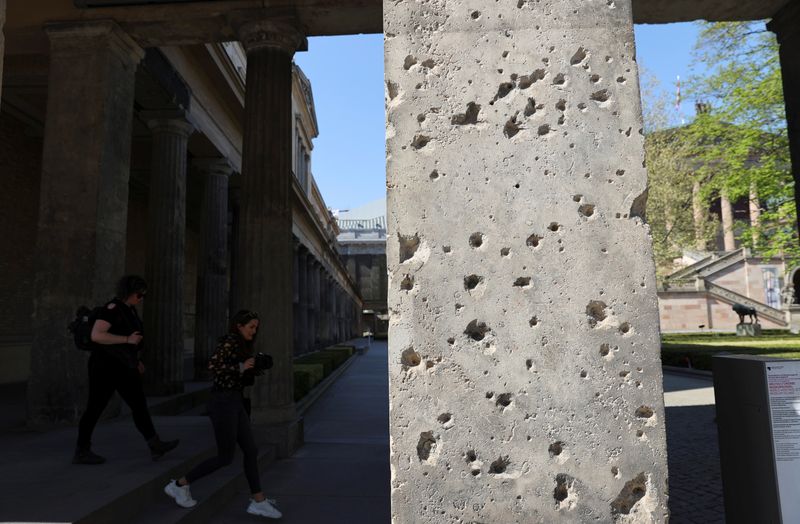

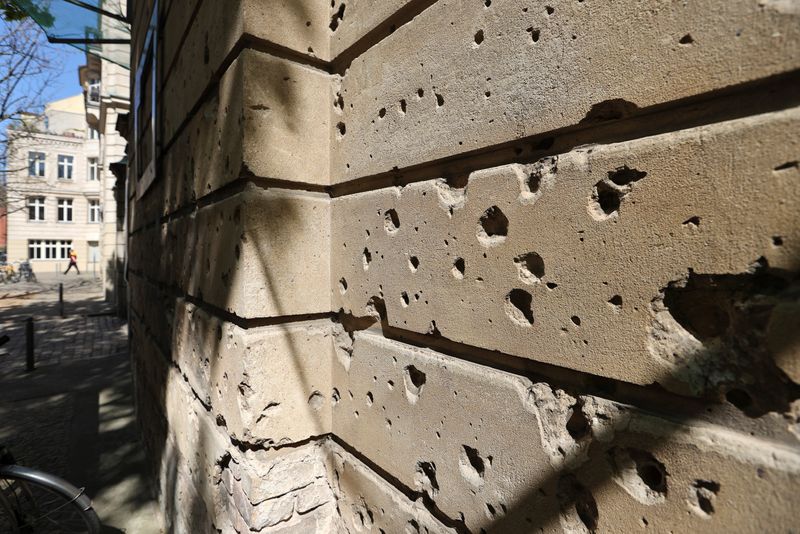

Facades in the centre are disfigured by bullet holes and shell damage, a reminder that Hitler’s Third Reich ended in devastating defeat, not the liberation it is hailed as today.

Thanks to the coronavirus, Chancellor Angela Merkel and President Frank-Walter Steinmeier will mark the May 8 “Day of Liberation” by laying wreaths at the Memorial to the Victims of War and Dictatorship, home to the tomb of the unknown soldier.

This replaces a previously planned larger ceremony including foreign diplomats and young people plus a range of events including an art installation documenting the last days of the war and tracing the path to democracy, which will now go online.

Nazism, the Holocaust and the devastation of war still shape German identity and politics.

“Today you can say we were freed from the Nazi dictatorship but most Germans were defeated. They were perpetrators, not victims of Nazism,” said Bjoern Weigel, curator of the “75th Anniversary of the End of the War” art project.

“You have to look at this differentiation to avoid a myth (of victimhood) taking hold,” he said.

The Battle of Berlin, in which Red Army tanks, artillery and infantry fought their way forward street by street in April and May 1945, reduced the Nazi capital to rubble.

It was one of the war’s bloodiest battles. Including assaults to encircle Berlin from Seelow and Halbe, more than a quarter of a million people died, say historians, although estimates vary and bodies are found every year.

SURRENDER

Germans fought on even after Hitler committed suicide on April 30 and the Berlin garrison surrendered on May 2. It took until May 8 for German generals to capitulate.

“In 1945, not all Germans felt happy. For many it was a catastrophe,” said Joerg Morré, director of the German-Russian museum at Karlshorst where the unconditional surrender was signed.

Vivid reminders of the battle still disfigure Berlin buildings, offering evidence of fierce fighting.

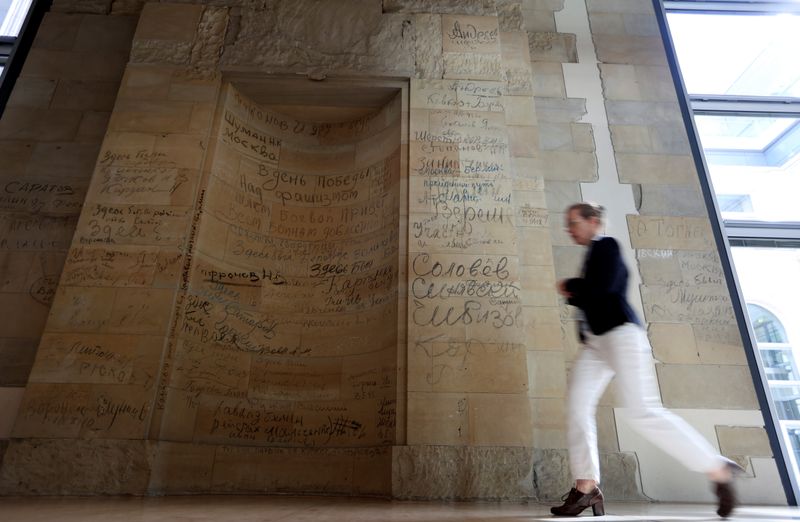

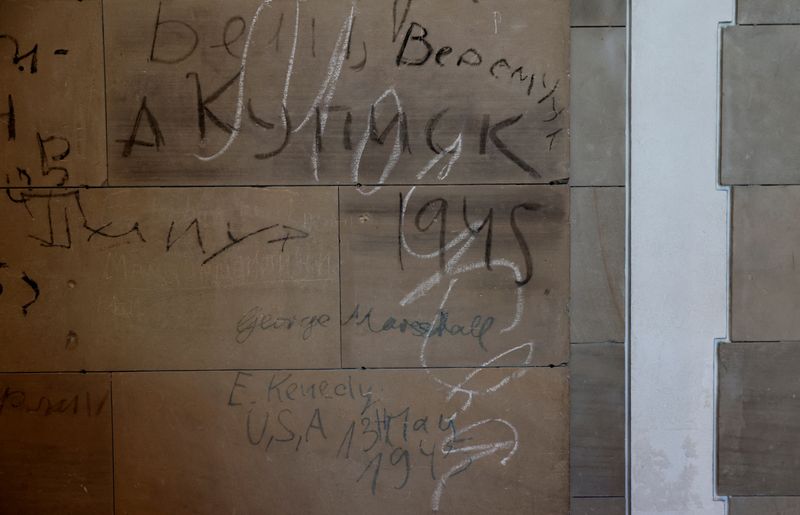

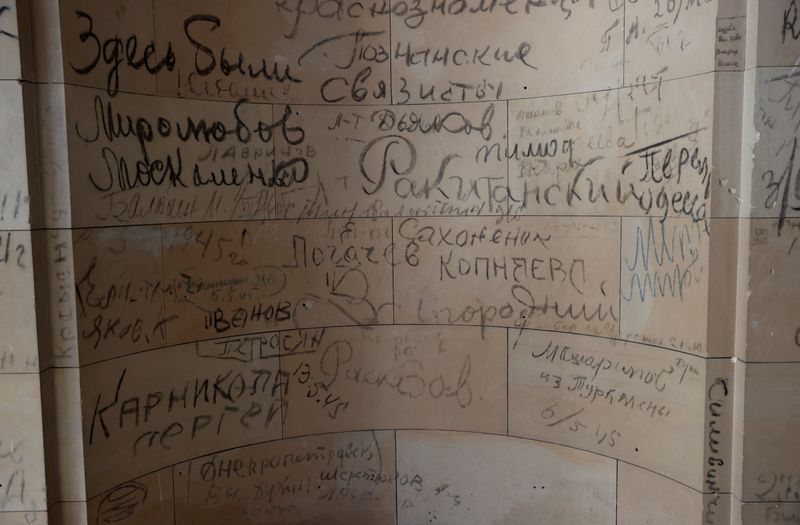

Traces of the battle range from obscene graffiti scrawled on walls inside the Reichstag by victorious Red Army soldiers to damaged facades of city museums, bunkers and bridges.

“People living here are aware of this but they don’t see it as being particularly relevant,” said tour guide Nick Jackson.

Locals should be allowed to reinvent their city, he said.

“Rebuilding and moving forward is a natural process that I don’t think is malicious,” he said, adding younger Germans like to see May 8 as a celebration of liberation and democracy.

In the last decade or so, some Germans have focused more on their own suffering during the war and prominent members of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), Germany’s third biggest parliamentary party, want to rewrite the history books.

As the rise of the right raises questions about Germans’ view of the past, it is even more important to stress the responsibilities linked to democracy on May 8, said Weigel.

“You can see the link between the Nazi era and now. What these people wanted when they voted Hitler in was not what they got,” he said.

(Reporting by Madeline Chambers; Editing by Giles Elgood)