WILMINGTON, Del. (Reuters) – Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden on Tuesday outlined an ambitious climate plan that would spend $2 trillion over four years investing in clean-energy infrastructure while vowing to cut carbon emissions from electrical power to zero in 15 years.

The plan signifies a more aggressive approach on climate policy than he adopted during the Democratic presidential primary – a nod to progressives within the party who have been clamoring for swift, bold action.

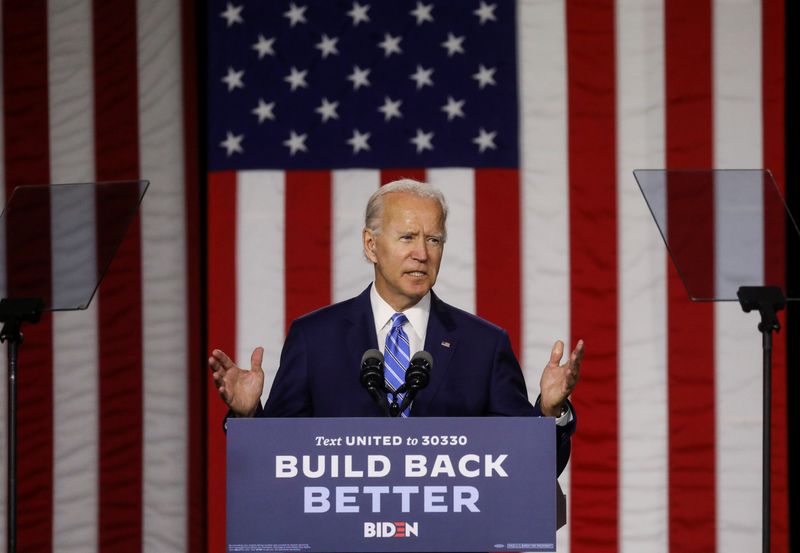

“Let’s not waste any more time,” Biden said at a campaign event in Wilmington, Delaware. “Let’s get to work now, now.”

Beyond the goal of reducing carbon emissions, Biden said his climate package would provide a badly needed jolt to a U.S. economy battered by the coronavirus pandemic, ultimately creating millions of new jobs in the clean-energy sector.

“When Donald Trump thinks about climate change, the only word he can muster is ‘hoax.’ When I think about climate change, the word I think of is ‘jobs.’ Good-paying union jobs that put Americans to work,” said Biden, who will face President Trump, a Republican, in the Nov. 3 election.

Biden’s revised climate plan would require the country to be producing 100% clean electricity by 2035, moving up his original target date by 15 years – a timeline borrowed from former presidential candidates Jay Inslee and Elizabeth Warren.

Since emerging as the prospective Democratic nominee, Biden has been pressed by activists in the party to adopt more expansive climate policies.

His proposal now would spend more money more quickly than his original approach, calling for $2 trillion in new spending during his first term as president, according to a copy of the plan released by his campaign. He had first suggested spending $1.7 trillion over a decade.

The plan would seek to boost the U.S. auto industry through incentives for manufacturers to produce zero-emission electric vehicles. And it would look to build 1.5 million new energy-efficient homes and public-housing units.

Biden’s plan also has a large environmental justice emphasis and would direct 40% of clean-energy spending toward disadvantaged communities in the shadows of refineries and power plants.

Activist groups such as the Sunrise Movement, which had been critical of Biden’s climate plans in the past, praised him on Tuesday for showing more urgency on the issue.

But two Republican congressmen from energy-producing states, Steve Scalise of Louisiana and Mike Kelly of Pennsylvania, blasted Biden’s proposal in a press call held by the Trump campaign.

They accused Biden of pandering to the party’s liberal wing and warned that instead of boosting the economy, the plan would do away with thousands of high-paying jobs and increase electricity costs, with middle- and low-income families bearing the brunt.

PAYING FOR THE PLAN

Climate change is less of a concern for many Americans this summer with the nation largely focused on the coronavirus pandemic and the recession. Less than 5% of U.S. adults said in a July 6-7 Reuters/Ipsos poll that the environment is a top priority for the country.

In comparison, 28% listed the economy or the nation’s rising unemployment as their top concern. Another 16% said it was healthcare.

Campaign advisers on Tuesday said the plan is a component of Biden’s overall economic recovery package, which they described as the largest mobilization of public investment since World War Two.

The campaign will further detail how it intends to cover the cost of the recovery package in the coming weeks, aides said, but pointed to Biden’s pledge to raise taxes on corporations and the wealthiest Americans and reverse Trump’s tax cuts for top-end earners.

Many of Biden’s proposals could be done through executive orders, his aides said. But the large-scale outlays would require congressional approval.

The American Petroleum Institute, a trade group in Washington, suggested Biden’s plan could harm the U.S. oil and gas industry, forcing the country to look to foreign sources of energy with lower environmental standards.

“You can’t address the risks of climate change without America’s natural gas and oil industry,” said Mike Sommers, the institute’s chief executive.

(Writing by James Oliphant. Additional reporting by Chris Kahn and Jarrett Renshaw.; Editing by Colleen Jenkins, Alistair Bell and Jonathan Oatis)