By David Lawder

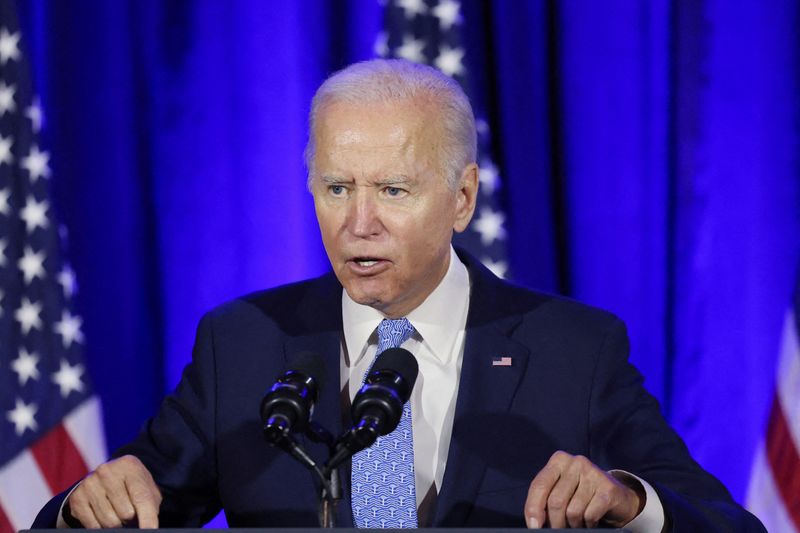

WASHINGTON (Reuters) -U.S. President Joe Biden signed two new executive orders intended to fight drug trafficking and criminal networks on Wednesday, allowing for new sanctions on Chinese companies trading ingredients of the opioid drug fentanyl and on criminal gangs in Brazil, Mexico and Colombia.

The Biden administration is keen to show it is taking action on a worsening U.S. opioid crisis that has fueled more than 100,000 U.S. drug overdose deaths in the year to April 2021, a 28% increase from the same period a year earlier, according to Centers for Disease Control data https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm.

The U.S. Treasury said it had imposed sanctions on 25 entities and individuals under new authorities granted under one of the executive orders that allows the department to target those benefiting from trafficking proceeds, regardless of any direct links to known drug kingpins or cartels.

The sanctions on Chinese companies include Wuhan Yuancheng Gongchuang Technology Co Ltd, which the Treasury says takes internet orders for precursor chemicals used to make fentanyl, as well as other firms it says are involved in the sale or transport of such chemicals.

In Brazil, Treasury imposed financial sanctions on Primeiro Comando Da Capital, or PCC, which was born in the prisons of Sao Paulo in the early 1990s and is now considered Brazil’s most powerful criminal organization, helping to flood Europe with cocaine.

The addition of PCC to the Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctions list follows moves in 2019 by the State Department and Department of Homeland Security to quietly add suspected PCC members to a list of organizations ineligible for a U.S. visa – a tactic used against organized crime group members elsewhere.

The Treasury has also targeted a list of drug kingpins, cartels and gangs in Mexico and Colombia, some of which were previously designated under narrower sanctions authorities.

The sanctions deny designated entities access to U.S. dollar transactions and freeze any assets they may hold in the United States. But organized crime groups in recent years have been shifting to crypto assets and other methods of avoiding the U.S. financial system.

To combat drug trafficking, the Treasury previously relied on the 1999 Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Act and an earlier 1995 executive order that were based on more traditional cartel structures with more easily identifiable leaders. The new structure allows the Treasury to target a broader range of individuals, such as those who knowingly receive property derived from drug trade.

“Today’s drug trade no longer relies on crops that require vast acreage, but instead on synthetic materials and precursor chemicals. Cartels operate in a more diffuse and decentralized way, hindering our ability to build comprehensive sanctions packages on drug traffickers,” one of the officials told reporters.

A second Biden executive order creates a new interagency council on transnational organized crime to improve cooperation between the departments of Justice, Defense, Homeland Security, Treasury and State and the Office of National Intelligence.

It aims to improve communications between the intelligence and law enforcement communities and the private sector to identify and target criminal networks, according to an administration fact sheet.

(Reporting by David Lawder in WashingtonEditing by Heather Timmons, Matthew Lewis and Rosalba O’Brien)