LONDON (Reuters) – The United Kingdom’s 25-year-old model of importing cheap labour has been up-ended by Brexit and COVID-19, sowing the seeds for a 1970s-style winter of discontent complete with worker shortages, spiralling wage demands and price rises.

Leaving the European Union, followed by the chaos of the biggest public health crisis in a century, has plunged the world’s fifth-largest economy into a sudden attempt to kick its addiction to cheap imported labour.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Brexit experiment – unique among major economies – has further strained supply chains already creaking globally for everything from pork and poultry to medicines and milk.

Wages, and thus prices, will have to rise.

The longer-term impact on growth, Johnson’s political fortunes and the United Kingdom’s on-off relationship with the European Union is unclear.

“It’s really a big turning point for the UK and an opportunity for us to go in a different direction,” Johnson, 57, said when asked about the labour shortages.

“What I won’t do is go back to the old failed model of low wages, low skills, supported by uncontrolled immigration.”

He said Britons had voted for change in the 2016 Brexit referendum and again in 2019, when a landslide election win made Johnson the most powerful Conservative prime minister since Margaret Thatcher.

Stagnant wages, he said, would have to rise – for some, the economic logic behind the Brexit vote. Johnson has bluntly told business leaders in closed meetings to pay workers more.

“Taking back control” of immigration was a key message of the Brexit campaign, which the Johnson-led “Leave” campaign narrowly won. He later promised to protect the country from the “job-destroying machine” of the European Union.

BREXIT ‘ADJUSTMENT’

Johnson casts his Brexit gamble as an “adjustment” though opponents say he is dressing up a labour shortage as a golden opportunity for workers to increase their wages.

But restricting immigration amounts to a generational change in the United Kingdom’s economic policy, right after the pandemic triggered a 10% contraction in 2020, the worst in more than 300 years.

As the EU expanded eastward after the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, Britain and other major European economies welcomed millions of migrants from countries like Poland, which joined the bloc in 2004.

No-one really knows how many people came: in mid-2021, the British government said it had received more than 6 million applications from EU nationals for settlement, more than double the number it believed were in the country in 2016.

After Brexit, the government stopped giving priority to EU citizens over people from elsewhere.

Brexit prompted many eastern European workers – including around 25,000 truckers – to leave the country just as around 40,000 truck licence tests were halted due to the pandemic.

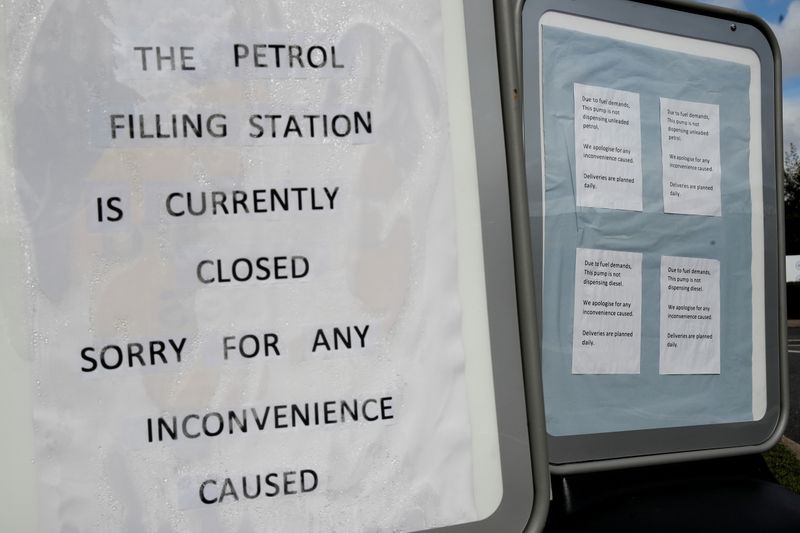

Britain is now short of about 100,000 truckers, leading to queues at gas stations and worries about getting food into supermarkets, with a lack of butchers and warehouse workers also causing concern.

“Wages will have to go up, so prices for everything we deliver, everything you buy on the shelves, will have to go up too,” said Craig Holness, a British trucker with 27 years experience.

Wages have already soared: a heavy goods vehicle (HGV) Class 1 driver job was being advertised for 75,000 pounds ($102,500) per annum, the highest the recruiter had ever heard of.

WINTER OF DISCONTENT?

The Bank of England said last month that CPI inflation was set to rise to 4% late this year, “owing largely to developments in energy and goods prices”, and that the case for raising interest rates from historic lows appeared to have strengthened.

It cited evidence that “recruitment difficulties had become more widespread and acute”, which the Bank’s agents had attributed “to a combination of factors, including demand recovering more quickly than expected and a reduction in the availability of EU workers”.

Johnson’s ministers have repeatedly dismissed the idea that Britain is heading for a “winter of discontent” like that which helped Thatcher to power in 1979, with spiralling wage demands, inflation and power shortages – or even that Brexit is factor.

“Our country has been running at a comparatively low rate of wage growth for a long time – basically stagnant wages and totally stagnant productivity – and that is because, chronically, we have failed to invest in people, we have failed to invest in equipment and you’ve seen wages flat,” Johnson said on Sunday.

But he did not explain how wage stagnation and poor productivity would be solved by a mixture of lower immigration and higher wages that fuel inflation which eats into real wages.

It was also unclear how higher prices would affect an economy that is consumer-driven and increasingly reliant on supply chains whose tentacles wind across Europe and beyond.

For some observers, the United Kingdom has come full-circle: it joined the European club in the 1970s as the sick man of Europe and its exit, many European politicians clearly hope, will lead it back into a cautionary dead-end.

Johnson’s legacy will depend on proving them wrong.

(Reporting by Guy Faulconbridge; Editing by Catherine Evans and Andrew Heavens)