LONDON (Reuters) – Britain on Saturday published the text of its narrow trade agreement with the European Union just five days before it exits one of the world’s biggest trading blocs in its most momentous global shift since the loss of empire.

The text includes a 1,246-page trade document, as well as accords on nuclear energy, exchanging classified information, civil nuclear energy and a series of joint declarations.

The “Draft EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement” means that from 2300 GMT on Dec. 31, when Britain finally leaves the European Union’s single market and customs union, there will be no tariffs or quotas on the movement of goods originating in either place between the United Kingdom and the EU.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson cast the deal as the final implementation of the will of the British people who voted 52-48% for Brexit in a 2016 referendum, while Europe’s leaders said it was time to leave Brexit behind.

Michael Gove, a senior British minister who campaigned alongside Johnson to leave the EU, said the deal would allow Britain to put some of the divisions of the nearly five-year Brexit crisis behind it.

“Friendships have been strained, families were divided and our politics has been rancorous and, at times, ugly,” Gove wrote in The Times. “We can develop a new pattern of friendly cooperation with the EU, a special relationship if you will, between sovereign equals,” Gove said.

The Brexit referendum exposed a United Kingdom divided about much more than the European Union, and has fueled soul-searching about everything from secession and immigration to capitalism, empire and modern Britishness.

Such musings amid the political crisis over Brexit have left allies puzzled by a country, the world’s No. 6 economy and a pillar of the NATO alliance, that was for decades touted as a confident pillar of Western economic and political stability.

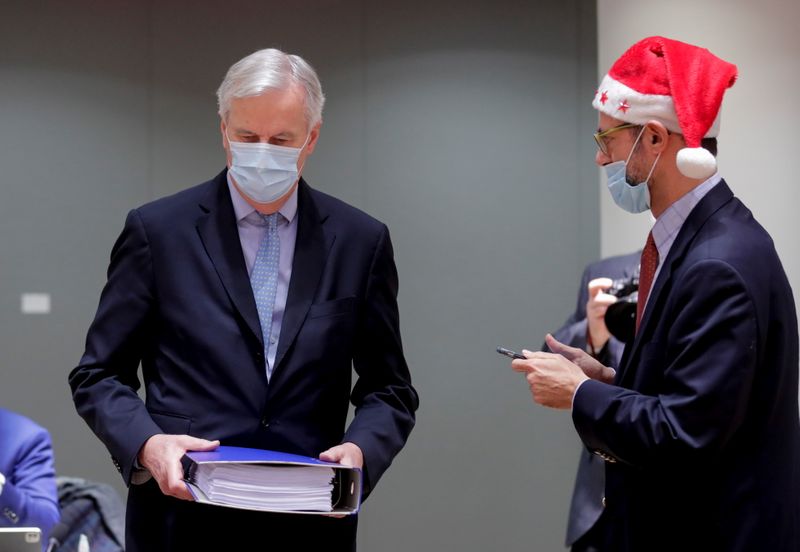

BREXIT DEAL

The two sides finally clinched a trade deal on Christmas Eve that explicitly recognises that trade and investment require conditions for “a level playing field for open and fair competition.”

If, though, there are “significant divergences” on rules between the two sides, then they can “rebalance” the agreement.

Each side will have an independent subsidy control adjudicator, though it was not immediately clear which body would do this in Britain, which had insisted on being free of any jurisdiction by the European Court of Justice.

On services, which comprise up to 80% of Britain’s economy, the two sides simply commit “to establish a favourable climate for the development of trade and investment between them”.

On fishing rights, Johnson agreed to a 5-1/2 year period to phase in new rules on what EU boats can catch in British waters, after which there will be annual consultations on the EU catch.

Britain will no longer take part in security sharing organisations and databases such as Europol, Eurojust and SIS-II, though there will be some cooperation for the exchange of passenger information and DNA, fingerprints and vehicle registration data.

The text includes many detailed annexes including on rules of origin, fish, the wine trade, medicines, chemicals and security data cooperation.

EU states are now working to implement the deal by Jan. 1 through a fast-track procedure known as “provisional application”.

However, the European Commission said in publishing the treaty that the fast-track approach would hold only until end-February as the European Parliament’s consent – expected in the first weeks of 2021 – is still needed to permanently apply it.

For the text of the draft deal: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/948104/EU-UK_Trade_and_Cooperation_Agreement_24.12.2020.pdf

(Writing by by Guy Faulconbridge, Additional reporting by Elizabeth Piper and Gabriela Baczynska; Editing by Mark Heinrich)