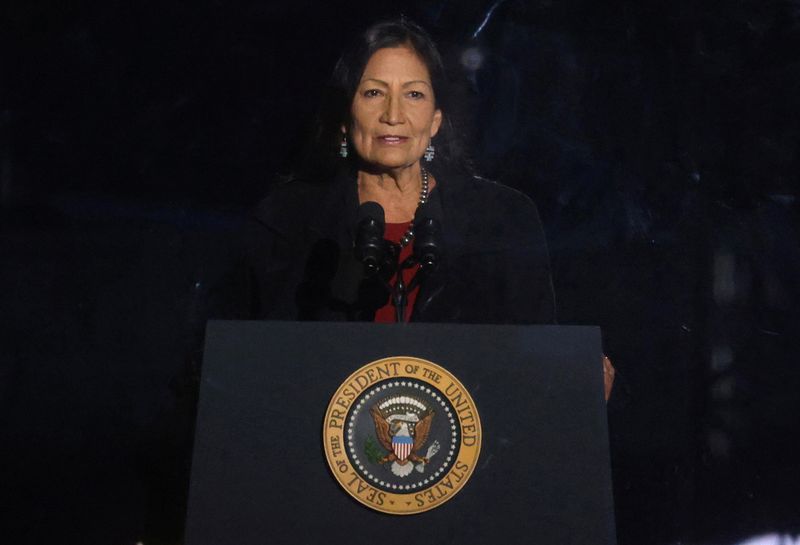

(Reuters) -A U.S. government investigation into the dark history of Native American boarding schools has found “marked or unmarked burial sites” at 53 of them, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said on Wednesday.

Haaland, the first Native American cabinet member, announced the investigation last year. In releasing preliminary findings during a press conference in Washington, she spoke through tears and in a choked-up voice.

“The federal policies that attempted to wipe out Native identity, language and culture continue to manifest in the pain tribal communities face today,” Haaland said. “We must shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past.”

Until Wednesday, the U.S. government had yet to provide any true accounting of the legacy of the schools, which used education to change culture so tribal land could be taken. Families were forced to send their children to the schools.

To compile Haaland’s report, researchers located records on 408 schools that received federal funding from 1819 to 1969, and another 89 schools that did not receive money from the government. About half the schools were run for the government by or supported by churches of various denominations. Many children were abused at the schools, and tens of thousands were never heard from again, activists and researchers say.

The report noted that “rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse” took place at the schools and is well documented, and that so far the investigation had found over 500 children who died while in school custody. Investigators said they expect to uncover many more deaths.

Haaland said she’s beginning a year-long “road to healing” tour to listen to survivors of the boarding school system. The next goals of the investigation are to estimate the number of kids who attended the schools, finding more burial sites and identifying how much federal monies went to churches that took part in the school system, among other issues.

She said Congress had provided $7 million to keep the research going this year, which she said was fundamental to helping Native Americans heal.

Experts said the first report on the investigation had barely scratched the surface of what needs to be examined. The Interior Department has identified more than 98 million pages of documents that may relate to the boarding school system within the American Indian Records Repository that still need to be evaluated. Tens of millions more pages housed regional branches of the National Archives and Records Administration also must be examined.

A former congresswoman from New Mexico, Haaland in 2020 introduced legislation calling for a Truth and Healing Commission into conditions at former Native American boarding schools. That legislation is still pending, and hearings on the most recent version of the bill are scheduled for Thursday before a U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States.

Deborah Parker, head of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition that’s assisting the Interior Department in its investigation, said the report just scratched the surface of the trauma.

“Our children had names. Our children had families. Our children have their own languages,” she said at the press conference. “Our children had their own regalia, prayers and religion before Indian boarding schools violently took them away.”

‘IDENTITY ALTERATION’

Researchers examined government records and spoke to Native Americans to prepare the report. The results detail a history dating to at least 1801, when the first such schools opened, and one in which education was used as a weapon.

Native American affairs, including education, were a War Department responsibility until 1849 and the military remained involved even after civilians took over, the report noted.

The schools were described as resembling military academies in their regimentation and strictness and emphasizing vocational skills. Police were called on to force families to send their children to the schools. Food was denied to families as another way to force them to surrender their children.

“These conditions included militarized and identity alteration methodologies – on kids!” said Bryan Newland, the assistant secretary for Indian Affairs at the Interior Department, who heads the investigation.

Conditions at former Indian boarding schools gained global attention last year when tribal leaders in Canada announced the discovery of the unmarked graves of 215 children at the site of the former Kamloops residential school for indigenous children, as such institutions are known in Canada.

Unlike the United States, Canada carried out a full investigation into its schools via a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The U.S. government has never acknowledged how many children attended such schools, how many children died or went missing from them or even how many schools existed.

The report released on Wednesday included recommendations for funding programs to preserve the Native American languages the schools tried to stamp out, and establishing a federal memorial.

(Reporting by Brad Brooks in Lubbock, Texas; editing by Donna Bryson, Aurora Ellis and Grant McCool)