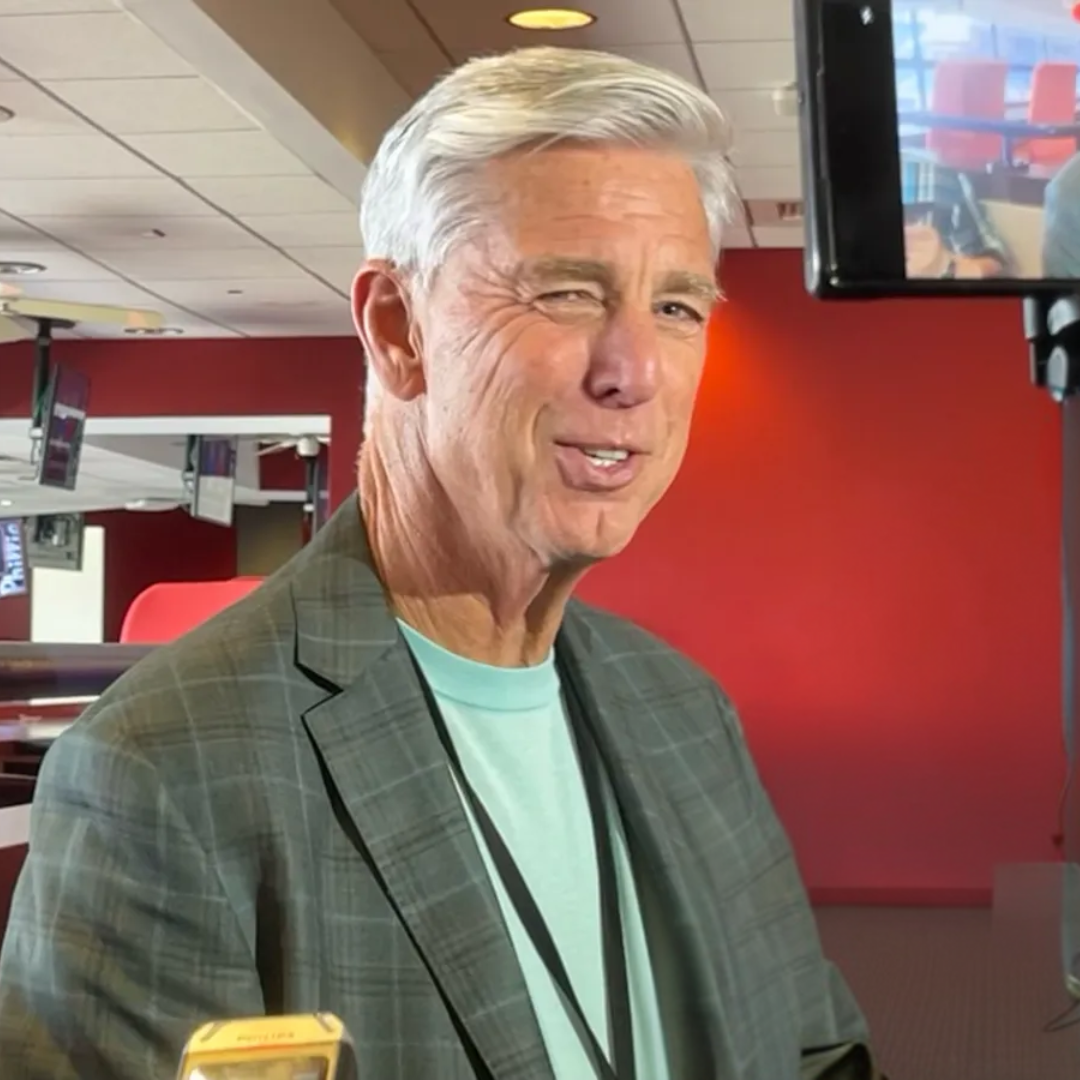

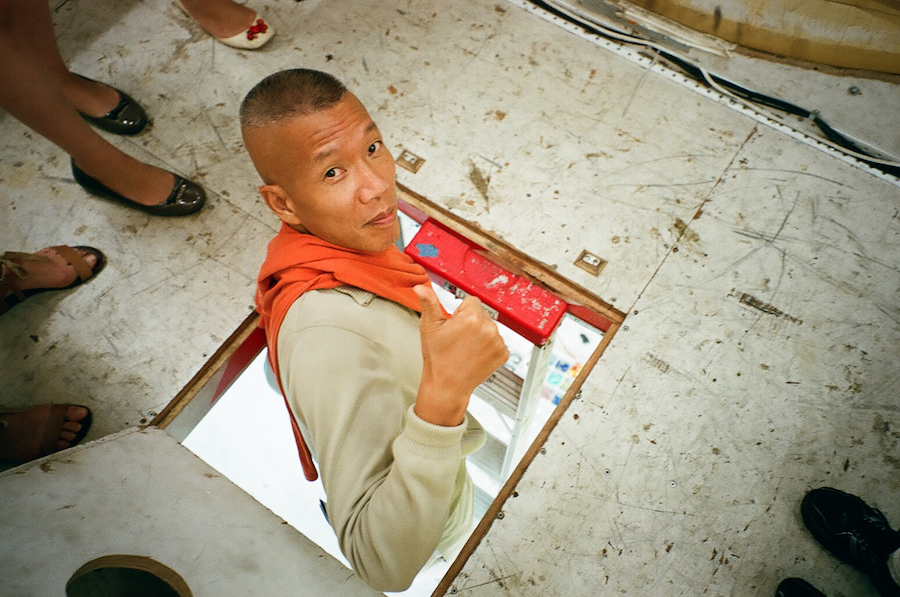

Save for two martial arts films he appeared in as a young man (“The Fall and Spring of a Small Town,” “Real Kung of Shaolin”), the renowned Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang has largely avoided the movies. After all he’s been busy, eking out a storied career creating pieces that involve fireworks, gunpowder and, in 2006’s “Head On,” a string of wolves connected from one side of a gallery space to another. In 2008 he contributed the eye-popping fireworks display to the opening ceremony of the Beijing Summer Olympics. That changes with “Sky Ladder: The Art of Cai Guo-Qiang,” a documentary about his life pegged to the eponymous piece, in which, on June 15, 2015, rungs rigged with fireworks reaches into the sky while connected to a balloon. Cai had tried four different times to mount the project, in places like Los Angeles and New York, where he’s resided since 1995. He only succeeded when he did in the far-off, remote Huiyu Island in his homeland, with only a few hundred in attendance. Luckily, filmmakers were there to document this beautiful feat. Cai talks to us from his cavernous studio in the East Village about the ephemeral nature of his work, moving from black gunpowder to colored and how his late grandmother finally got to see one of his pieces live. Since becoming involved with this documentary, you’ve seen what it’s like to work in the film world. What are some things you noticed about working in this very different, very commercially-driven medium? RELATED: What it’s like to meet Sonia Braga, star of “Aquarius” Film and video actually seem like they’d compliment some of your work, like “Sky Ladder” or your fireworks pieces. They’re ephemeral by nature, which is to say they occur only once and can reach a larger audience by being documented. In fact, “Sky Ladder” went viral shortly after it happened in 2015, because someone leaked cellphone footage of it on Facebook. What do you think of that? It’s very different, in terms of presentation, than your piece for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. There’s an ephemeral nature to some of your pieces that wouldn’t benefit from being documented on film. Even with a piece like “Head On,” which has a stream of wolves stretching from one side of a gallery space to another, it’s about the viewer standing in that space with the piece, for as long as it’s being exhibited. You dedicated “Sky Ladder” to your grandmother, who passed a month after the piece was revealed. Tell me more about your relationship. There’s debate shown in the film before the piece went up about spending money on something that would only be seen by a relatively small group of people in a remote part of China. Why did you choose that place? You’ve long done paintings with black gunpowder. You recently made the switch to color. What was the motivation for that? Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge

When the film first premiered at Sundance, that’s when Netflix became interested in becoming the distributor. They then invested to re-edit the film for it to be better suited to their audience. That’s quite different from making art. You don’t hear of a collector or a museum spending money to edit the artwork they acquired.

The clip on Facebook came as a complete surprise. When I made the piece, for my grandmother’s 100th birthday, I was helped by around 400 villagers in Huiyu Island, who participated and watched this artwork. I was expecting no larger than this group as an audience. However, when the shaky cellphone footage leaked on Facebook, within two days, it had over 30 million views. It really showed me how new media provided new possibilities for art.

For the Olympics you had major media partners, like NBC and the Olympic Committee, who spent a long time raising people’s expectations. “Sky Ladder” was a personal project. We didn’t apply for an official government permit; it was done secretly and it happened at the crack of dawn. Popularity on social media gave me a new perspective as an artist — and I’m sure other cultural institutions and practitioners have experience this as well. If you compare the communication of the Olympic Opening Ceremony as pushing a button to light all the city street lamps, the way this piece was leaked was almost like pollen being spread in a garden.

Although my work has always been visual, or dependent on the visual, the element of time has always been significant. I have been trying to dialogue with the unseen worlds and have been searching for a sense of eternity in a transient moment. For Head On, although there are 99 wolves chasing each other, crashing into a glass wall, and eventually returning onto themselves, you can also see it as a time-lapse view of one wolf at various stages in time. A piece that contains movement can be considered as a static piece, like a roll of film stretched out in space.

Ever since I was a young boy my grandma always told me I was her favorite grandson. And she was my earliest fan, supporter and collector. My dad was a painter himself, but my grandma always told me I was her favorite artist. She told me, “Your father’s paintings are good enough to be used as tinder for my cooking.” [Laughs] She told my dad that, too, not just me. As I traveled the world and realized projects in five continents, my grandma was never able to see any projects in person. It was always on my mind to have her see my work. On January 1, in 2015, I hosted a 100th birthday celebration for her. That’s when I noticed her health was declining, and I knew I had to act fast on this project. Two or three days before the planned realization date, I saw that my grandma’s health had declined to the point where she couldn’t see it in person. I felt an immense sense of defeat. But thanks to modern technology, we had an iPad and an iPhone so she could see it immediately. As I watched the film I was very glad I did precisely that.

In China, there’s a saying: When you’re away from the Emperor, the sky is taller. It was easier for us to realize the piece without having to go through safety permit applications. I knew that if the villagers were able to help us keep the secret, this had a chance in succeeding. I had tried to realize Sky Ladder in big cities like Los Angeles and Shanghai, and it didn’t succeed. However, in this village, everyone there understood the climate and the currents of the sea. They knew precisely at what hour the wind would subdue and when it was most favorable to realize the piece.

Over 30 years ago, when I first moved to Japan, I already knew about colored gunpowder as a material. Back then I decided to stick with black gunpowder, because I wanted to pursue a pure, spiritual and absolute direction. After decades of experimenting with gunpowder, I decided to take on the challenge of working in color. Not only because color has an immediate relationship with painting and art history; it’s also more rich and complex. It gives me new challenges in confronting the issue of painting in the context of today. It’s not easy. As I age, I notice that color can deliver and communicate my emotions in a way that’s more subtle. To me, painting is another ladder, one that carries me back to the beginning of my artistic pursuit when I was a young artist. This pursuit has always been to be a painter.

Cai Guo-Qiang on making ‘Sky Ladder’ for his grandmother

Wen-You Cai/Netflix