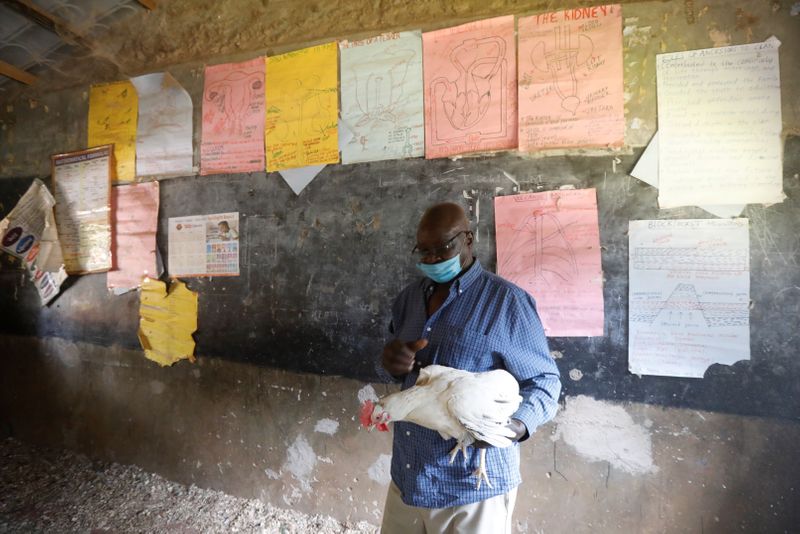

MWEA, Kenya (Reuters) – Rows of spinach sprout in the sports field where the students of Roka Preparatory school once played football, and clucking chickens fluff their feathers in sawdust-covered classrooms where children once sweated over their exams.

No students have thundered down these eerily quiet corridors since March, when Kenya abruptly closed its schools three days after the first case of COVID-19 was detected. The loss of income means some private schools will shut permanently.

“I had to think of how to use the classrooms because they were haunting,” James Kung’u, the school’s director, told Reuters as he tended vegetables in the fields around 100 kilometres (62 miles) northeast of the Kenyan capital Nairobi.

“When you wake up in the morning, and you find the empty classes looking at you – as an investment, (it’s) very discouraging.”

Kenya’s 11,400 private primary and secondary schools serve about 2.6 million students, the Kenya Private Schools Association says. They vary from bare classrooms charging a few thousand shillings a term to ultra-manicured campuses serving the nation’s elite.

Peter Ndoro, the association’s chairman, said around 150 schools have already gone bust. Most of the 158,000 teachers working in private schools are on unpaid leave, he said.

While some schools have been able to oversee distance learning, in others the pupils – and the teachers – have no way to connect to the internet. They have to look for creative ways to make money.

But Kung’u said turning to farming means Roka, which had 530 pupils in March, will not close. He said to date, the school had lost at least 20 million shillings ($184,500) in school fees but was still paying partial salaries to teachers.

Schools are expected to stay closed at least until January. Kenya’s education ministry says they can only reopen when the number of COVID-19 cases drops substantially.

As of Sept.9, Kenya had 35,460 confirmed coronavirus cases, 607 deaths and 21,557 recoveries, the health ministry said. The rise began to slow in August but its unclear whether that is due to lower rates of testing due to a shortage of materials.

(Additional reporting by George Obulutsa; Writing by George Obulutsa; Editing by Katharine Houreld and Alexandra Hudson)