With “Dunkirk,” Christopher Nolan wants you to feel like you’re really there. The latest from the acclaimed and highly successful filmmaker is a World War II epic, dropping us into the aftermath of the Battle of Dunkirk, in which 400,000 English soldiers were trapped on a beach in the north of France. Home was a short trip across the sea, but they were surrounded by the German army. Their rescue is the stuff of legend.

But Nolan doesn’t want you to get bogged down in details. “Dunkirk” isn’t a Wikipedia movie. It’s no mere history lesson.

“The most important thing for me was to demonstrate what it felt like to the people who were really there,” he says. He didn’t want there to be too much information or an abundance of war movie cliches. “I wanted to tell an intensely subjective story that gave the public a wider view of what happened, but without the need for [shots of] barracks, generals and maps.”

He also didn’t want to use special effects. He wanted every plane, every ship, every location to be real.

“With this film, I realized the true value of the genuine, of authenticity.” When you see a shot with a thousand soldiers lined up on the beach, there really are a thousand actors. “When you see real photos of this, it immediately catches your attention. It’s interesting to give something like this to the audience, to show what it was like to be formed there, waiting in the middle of nowhere for days.”

The cast of “Dunkirk” is huge, mostly filled with extras. There are big names littered about: Tom Hardy as a hotshot pilot who guns down enemy planes; Kenneth Branagh as an anguished Commander trying to get his boys home; Mark Rylance as one of many English civilians who drove their boats across the ocean, ferrying soldiers back home. But many of our leads are unknowns — young actors in their first big film. One of those is Fionn Whitehead, who plays Tommy, a private who’s the closest thing this ensemble picture has to a lead.

“We needed young strangers to play those characters,” Nolan explains. “I didn’t want 13-year-olds doing 19-year-old roles. We wanted people to see guys with no expectations about whether they will survive or not.”

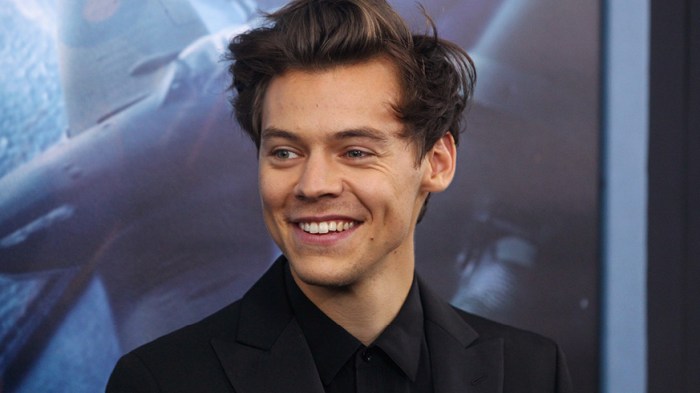

And then there’s Harry Styles. Nolan was having trouble casting the role of Alex, one of the other key young soldiers. As they searched, The One Direction sent them an audition tape.

“We told him, ‘Well, if you want to come in like any stranger and try this thing you’ve never done before, you’re welcome,’” Nolan recalls. Styles did just that. After what Nolan calls “audition workshops” — in which actors spend several days switching parts, acting alongside each other, forming a group — he felt Styles was “perfect.”

It helped that Nolan definitely isn’t up with popular music. “Harry who?” he jokes. “When the auditions took place, I did not know who he was. My children knew who he was, but I hadn’t seen much of him, because of my age.”

Having a big time star dominate the conversation over one of his films reminds Nolan of when he cast Heath Ledger as the Joker in “The Dark Knight.” “That raised lots of eyebrows of disapproval or doubt, because they didn’t know how he would work,” Nolan remembers. “But it’s part of my job to look for that potential.”

“Dunkirk” is an intense experience, even moreso than his three “Batman” movies or “Inception” or “Interstellar.” It demands the audience pay attention, not look at their smartphones, keep their brain switched to on. But Nolan swears he doesn’t have any loftier ambitions than to keep you watching the screen.

“My goal is first and foremost to entertain,” Nolan explains. “What cinema can do for the audience is give them an invigorating experience that they could not safely experience in their lives — that will take them to a place where they would never imagine, be it a place of fiction or Dunkirk. My hope is that at the end of the film, the audience will take a break and think, ‘OK, that was an experience.”