CLINCHCO, Virginia (Reuters) – Cosam Mullins mined coal in the western hills of Virginia for much of his working life. Now, with mining jobs hard to find, he’s cleaning up the mess the industry left behind.

The 68-year-old operates a bucket loader scraping away red, rocky waste dumped years ago by failed coal mine operators in a valley in the town of Clinchco, Virginia.

The $17.50 an hour before overtime he makes cleaning up massive “gob piles,” as the locals call them, is less than what he earned in decades as a miner. But it’s a paycheck.

“If this work goes away, I don’t know what I would do,” Mullins said.

Appalachia, long the heart of the U.S. coal-mining industry, may be set for a surge in jobs like Mullins’ if President Joe Biden is successful in his ambitions to transition the United States to a cleaner energy economy to fight climate change.

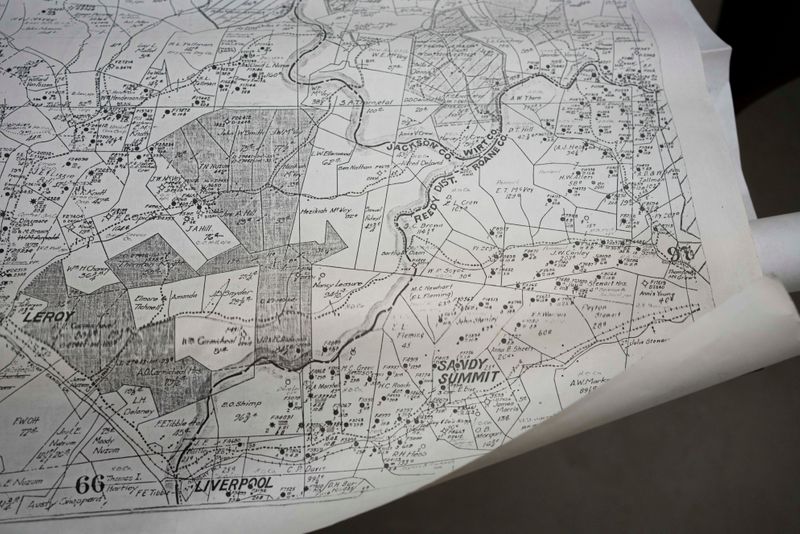

As part of that effort, the Biden administration wants to spend around $16 billion to help begin to clean up orphaned oil and gas wells and abandoned mine sites, many of which have been leaching toxins into the soil and spewing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere for decades. There are up to millions of abandoned wells and tens of thousands of mine sites.

The proposal, which is included in the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure package being debated in Congress, could help transform regions scarred environmentally and economically by the boom-and-bust cycles of drilling and mining.

While the cleanup jobs won’t last forever, they will buy precious time for fossil fuel-producing regions like Appalachia and parts of the West to diversify their economies to something new, the administration says.

The White House sees the proposal as bolstering a more comprehensive program to invest in energy communities that includes providing essential infrastructure like broadband internet, which is also in the bipartisan bill.

The U.S. Department of Commerce last week also announced an additional $300 million in funds for hard-hit coal, oil and gas, and power plant communities – intended to be used for boosting new industries or scaling existing ones, infrastructure development, and workforce training.

“I’m glad that somebody recognizes the problem,” said Lee Booth, a regional director at Savage Services, the private company that employs Mullins, his 20-year-old son Troy, and roughly 30 other workers in Clinchco.

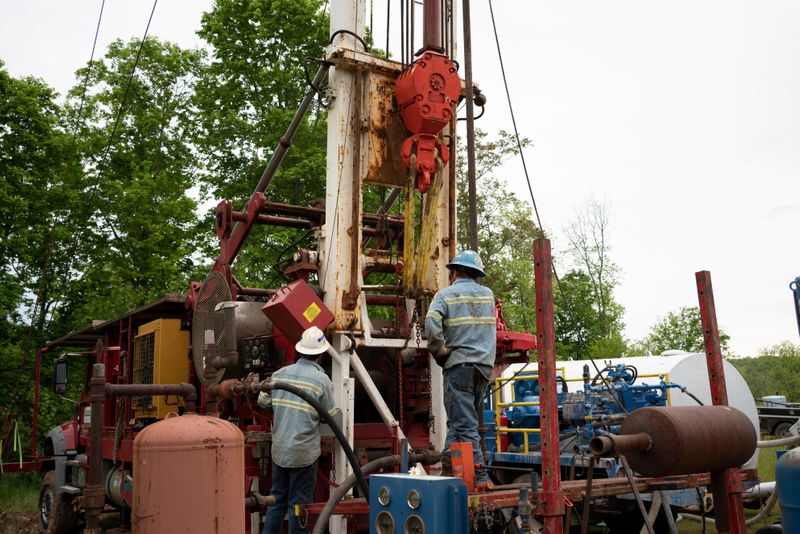

Scott Freshwater, 62, the owner of ConServ Inc in West Virginia, said Biden’s plan would be good for business. More than a third of his 80 employees plug leaky wells, with the rest working on projects like maintenance of compressor stations and pipelines.

“This federal funding will accelerate this work,” he said.

Some, however, say the cleanup jobs alone may be too few, too temporary and too poorly paid to have much of an impact.

“The only way to fully replace jobs that are at risk is to establish major manufacturing centers in coalfield areas that will employ hundreds at a time for decades, not dozens at a time for four to five years,” said Phil Smith, a spokesman for the United Mine Workers of America, which represents U.S. coal workers.

Critics say the funding could amount to a taxpayer bailout for industries that should have been forced to clean up their own mess.

A report from West Virginia-based environmental consulting firm Downstream Strategies said the funds proposed by the administration for coal cleanups would create around 2,700 new jobs in West Virginia, Ohio, and Virginia.

SMOLDERING

Waste piles are common at former mine sites across Appalachia, and sit smoldering in places because they contain trace amounts of flammable coal.They are also structurally dangerous. The piles in Clinchco are up to 40 feet (12 m) thick and at risk of collapse, as are other features of abandoned mines. Last year in Dante, a few miles away, heavy rains on abandoned coal mine entrances caused two landslides that temporarily evacuated 16 homes.

“It’s detrimental to economic development,” said Erin Savage, a senior program manager at the nonprofit Appalachian Voices, which advocates for coal mine reclamation.

“Why would you want to go and build a new business in a place where you might have to worry about some sort of mine feature potentially damaging your investment?”

Many of the companies that ran the mines are long gone – bankrupted by the ups and downs of a notoriously volatile industry, leaving the federal government to pick up much of the cleaning bill.

Biden’s infrastructure bill would inject about $11.3 billion into an under-funded federal program called Abandoned Mine Land (AML), which was set up to handle cleanups of mines abandoned before 1977 but has been struggling to keep up with the costs.

The bill also has something for industry: it could reduce fees on coal production that mining companies must pay to ensure cleanups are funded, but which detractors say add to the pressures that send companies into bankruptcy.

A deal worked out by West Virginia Democratic Senator Joe Manchin and Republicans, including Senator John Barrasso of top coal-producing state Wyoming, proposes cutting the fees for surface miners by nearly a third from 2012 levels.

The senators did not respond to requests for comment about the fee cut.

Some affected communities have already felt the impact of cleanups.

Daniel Kestner, a reclamation program manager at Virginia’s Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, said reclaimed coalfields in Appalachia have started to attract tourists in recent years, including all-terrain vehicle riders who come to gawk at reintroduced populations of elk in the hills.

But any new influx of federal money should have ambitious goals, including economic diversification, Kestner said.

“It should be flexible enough to be used not just for reclamation but for repurposing, for things such as battery storage, and solar plants and if there is the option for wind power,” he said. Money could also be used for agriculture projects and public parks, he said.

For Mullins and his son Troy it’s the work itself that matters.

“I’m hoping that there will be enough work for me to do this for the rest of my life,” said Troy Mullins.

(Editing by Richard Valdmanis and Sonya Hepinstall)