KINGSTON (Reuters) – Barbados’ declaration of a republic on Tuesday may fuel fervor in other Commonwealth countries to follow suit, but experts say removing the queen requires overcoming political hurdles that have for decades stymied republican initiatives.

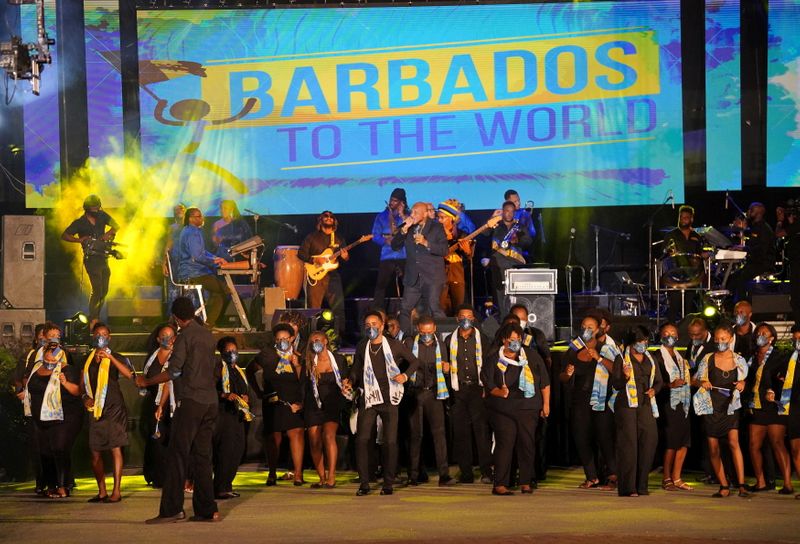

Barbados inaugurated President Sandra Mason as its head of state on Tuesday to replace Britain’s Queen Elizabeth in a ceremony attended by Prince Charles, marking a cordial severing of ties to the monarchy.

It was able to do so thanks to the Labor Party’s sweeping parliamentary majority as well as a constitution that allowed the change without a referendum – conditions that may not materialize elsewhere.

In nearby Jamaica, which is among the 15 remaining nations that still recognize Queen Elizabeth as sovereign, polls show that voters would support the declaration of a republic. On the streets of the capital Kingston, some people said the time was ripe to follow Barbados.

“I think we can start the process,” said Abraham Carter, 53, a musician. “(The monarchy) is not of great benefit to us.”

Jamaica’s two main political parties have for nearly five decades publicly supported the creation of a republic but have never proceeded with the required plebiscite.

“Once one party says it is for something, the other party says it is against it,” said Sir Ronald Sanders, a senior fellow at Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the University of London and the ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States.

“The expected outcome is it would become a political football.”

Sanders, nonetheless, expects Jamaica will become a republic in the next decade as ties to the United Kingdom become less relevant.

The office of Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness did not respond to a request for comment.

With the creation of the Republic of Barbados, 15 members of the Commonwealth – including the United Kingdom – still recognize Queen Elizabeth as their sovereign.

The Commonwealth is a grouping of 54 nations, most of which are former British colonies.

GLOBAL ATTENTION

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, whose party won parliament in a 2018 landslide, attracted global attention by leading the Barbados republican effort. She has taken advantage of the spotlight to demand greater sacrifices by industrialized nations to help small Caribbean nations protect themselves from climate change.

But even though removing the queen can be politically attractive, it has not always worked.

Republican referendums failed in 1999 in Australia and in 2009 in the Caribbean nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

The defeat in Australia was widely attributed to disputes within the republican ranks over how a president would be chosen. In St. Vincent, opposition leaders opposed it in the hopes that sinking the referendum would boost their standing in the 2010 general election.

Montreal-based market research group Leger released a poll in March showing most Canadians feel the monarchy is outdated.

But removing the monarchy in Canada would require altering the constitution and ratifying the change in 10 provinces and three territories, a complex process that Canadian political leaders have shown little interest in.

The issue of republicanism can be easily politicized, said Kristina Hinds, Head of the Department of Government, Sociology, Social Work and Psychology at The University of the West Indies Cave Hill Campus in Barbados.

“These kinds of things make a referendum difficult when there is a lot of misinformation put out there for purposes that have nothing to do with an actual transition and are more about political parties stirring up their bases,” Hinds said. (This story has been corrected to show Jamaica could become a republic, not leave the Commonwealth, in paragraph 9)

(Reporting by Kate Chappell in Kingston and Brian Ellsworth in Washington, with additional reporting by Steve Scherer in Ottawa and Robertson S. Henry in Kingston; Editing by Daniel Flynn and Mark Heinrich)