WASHINGTON (Reuters) -The U.S. Congress is poised for a long battle over President Joe Biden’s infrastructure investment plan as Democrats argue with Republicans and among themselves over the $2 trillion cost and how the money should be parceled out in coming years.

Democrats, with effective control of the Senate and a slim majority in the House of Representatives aim to deliver a final bill for the Democratic president to sign into law between July 4 and early September.

They have said they want Republican support for the plan, but have also pledged to move unilaterally if they cannot make prompt progress.

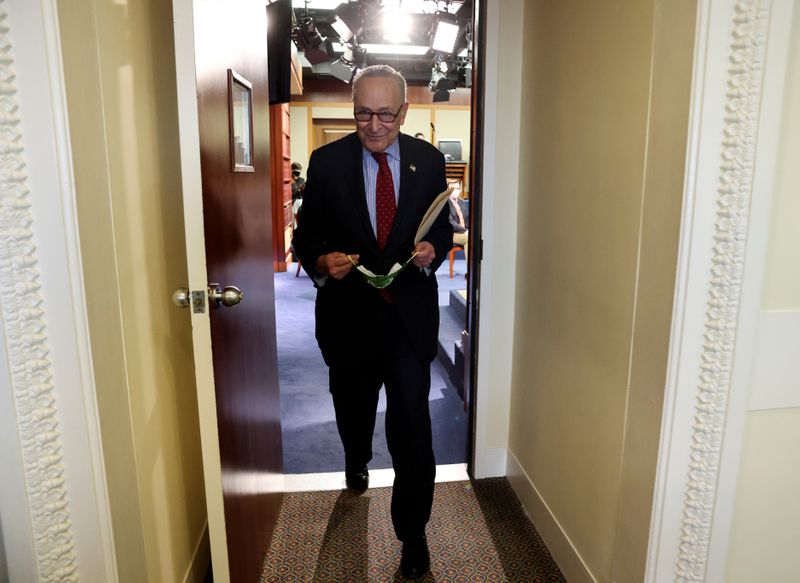

Democratic Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer invoked special fast-track budget rules to pass Biden’s recent $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill without Republican support. Schumer may have to go that route again, as Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell said on Wednesday he would not support tax increases or deficit spending in the bill.

“I’m going to bring Republicans into the Oval Office, listen to them, what they have to say and be open to other ideas,” Biden said in a speech in Pittsburgh on Wednesday unveiling the proposal. “We’ll have a good-faith negotiation with any Republican who wants to get this done,”

Liberal Democrats urged Biden to be more ambitious.

“Needs to be way bigger,” Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said on Twitter. Senator Ed Markey, a fellow progressive, has called for $11 trillion in spending over the next decade.

The Associated General Contractors of America, a construction group, praised the job creation that Biden’s plan would ignite, but attacked a measure it said would provide new protections for workers trying to join labor unions.

Biden’s plan initially calls for $2 trillion in new spending on everything from roads and bridges to broadband and elderly care, along with higher corporate taxes. Economists say the measures could create millions of blue-collar jobs.

Biden may also unveil a second spending package in April.

Republican former President Donald Trump had pledged infrastructure legislation in 2017, but it never got off the ground in part because of partisan disagreements over funding mechanisms.

Last month, Congress passed Biden’s coronavirus aid package without Republican support.

This time around, a dizzying array of congressional committees, ranging from House and Senate tax-writing panels to those that oversee health policy, the environment and transportation, are expected to struggle to find consensus.

ARRAY OF QUESTIONS

Many Republicans are wary of Biden’s infrastructure plan, especially if it is financed with tax increases. Some moderate House Democrats have said they will only support it if there is a bigger write-off for state and local taxes.

An array of thorny questions, including whether to use the legislation to lower the cost of prescription drugs, could produce delays along the way.

Sam Graves, top Republican on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, lamented that only 25% of the proposal was devoted to transportation infrastructure like roads and bridges and objected to tax increases.

Graves called on lawmakers to back proposals that could gain bipartisan support. Bill Shuster, a retired Republican congressman who was chairman of the transportation and infrastructure panel, predicted that elements like green energy and broadband investment could gain backing from both Democrats and Republicans.

Current and former lawmakers say it may take until September to pass the bill. The environment gets more difficult after that point as moderate Democrats could be pressed to defend Biden’s deficit spending ahead of the 2022 congressional elections.

(Reporting by Richard Cowan and Makini Brice; Additional reporting by Steve Holland in Pittsburgh; Editing by Andy Sullivan, Paul Simao and Peter Cooney)