SACRAMENTO, Calif. (Reuters) – A California case worker hears screaming as she tries to conduct a telephone session for a child abuse prevention agency; an Oregon doctor sees signs of abuse a teacher might have spotted days earlier.

Social distancing restrictions aimed at curbing the spread of the coronavirus have taken a steep toll on the already fragile systems U.S. cities and states use to track and prevent child abuse and neglect.

Chronically understaffed and underfunded agencies across the country say calls to the hotlines they rely on to flag abuse and neglect are down by as much as 70%.

Teachers report U.S. child abuse cases far more than any other group of people, but stay-at-home restrictions have curtailed their collective ability to look out for children’s well-being. Doctors, who also report many cases, are typically not seeing children for routine checkups at this time.

“As many as two-thirds of all cases of child abuse and neglect are never reported and unfortunately during a time like this my concern is those children plus some are out there and have no way of being seen,” said Bobby Cagle, chief of Children and Family Services for Los Angeles County, the most populous in the United States with 10 million residents.

The county’s child abuse hotline is the only way Cagle’s agency learns of suspected abuse, he said. Calls dropped from about 1,000 per day to as few as 400 as soon as the region’s schools were closed to slow the spread of coronavirus, he said.

Such drops are typical during summer break or over Christmas, when reports of abuse drop by half or more and teachers are unable to look out for kids, Cagle said. But in those cases, the kids come back in a few weeks and teachers can have their eyes on them again.

Now it could be months before a return to school.

Along with child abuse agencies throughout the country, Cagle’s team is trying to alert residents through outreach campaigns that they can report child abuse too.

In a separate effort, California Governor Gavin Newsom has made about $40 million available to help foster children and $7 million to help social workers better reach at-risk families during the pandemic.

Sheila Boxley, president of the Child Abuse Prevention Center in Sacramento, said some children were in homes where parents may be under unusual stress or living with domestic violence, substance abuse or mental disorders — known triggers for child abuse.

In Georgia, Oregon and other states, child welfare administrators are offering tips to teachers for spotting abuse even if their contact with students is only virtual or through online classroooms.

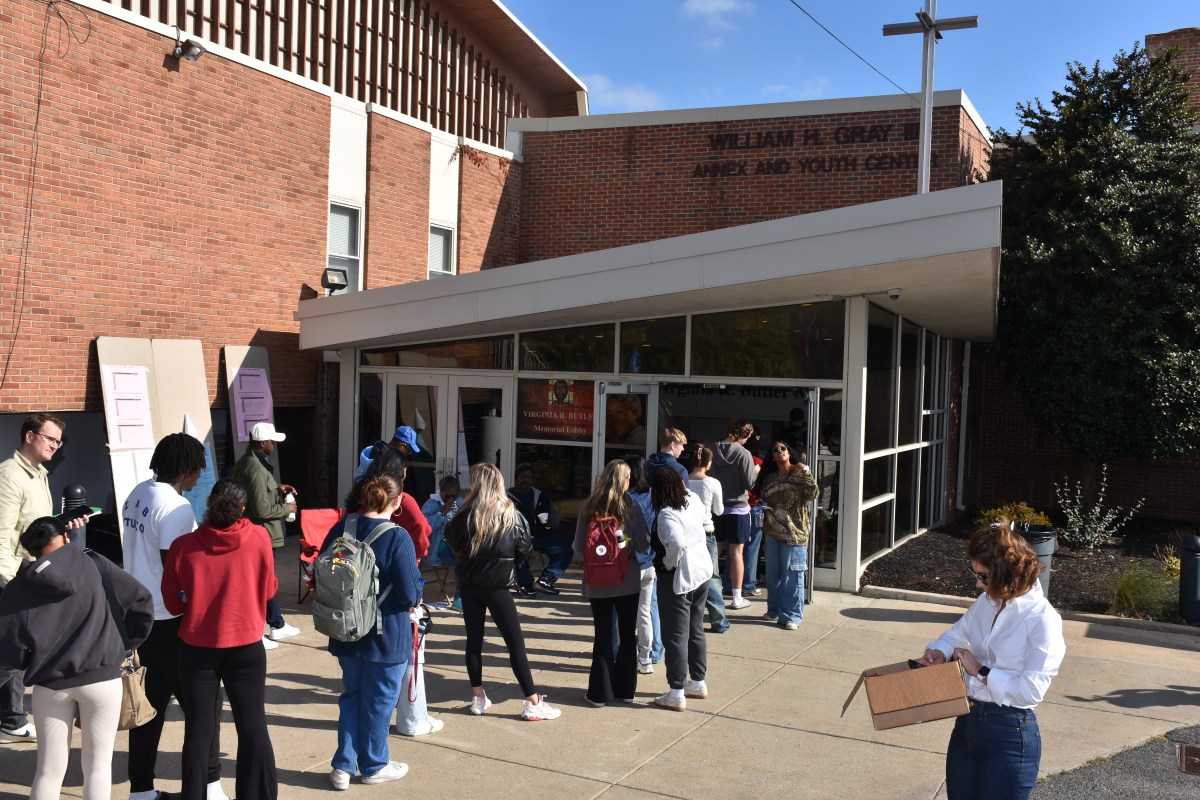

In Los Angeles, the Children’s Bureau, a nonprofit child abuse prevention organization, last week held a drive-through event in the West Adams neighborhood, handing out 1,000 packages of diapers and hundreds of meals to families in a line of cars stretching nearly a mile.

Ron Brown, the group’s president, said the hope was that by easing stress on families, anger and frustration would be less likely to erupt into abuse.

Case workers at the group’s Orange County locations are slipping notes with a child abuse hotline number into lunches sent home to children in needy families who are not in school, and sending art supplies to families where parents and children seem to be at wits end, said director Michele Essex.

TELL-TALE SIGNS

In Oregon, new child abuse cases have dropped by 72% since the enactment of social distancing measures. Doctors there are already reporting more severe child abuse than usual, said Becky Jones, executive director of the Oregon Network of Child Abuse Intervention Centers.

Like others, she said a teacher or pediatrician might have noticed tell-tale signs invisible to a neighbor or family friend, before the abuse took a turn for the worse.

Carol Chervenak, an Oregon physician who specializes in child abuse, said cases at her clinic initially dropped after Oregon’s stay-at-home order was enacted. But they shot up again over the past two weeks.

She said she recently treated a child with markings on the neck indicating strangulation – bruises that would likely have been recognized by a teacher trained in spotting child abuse. Other children, confined at home all day with parents who use drugs, are testing positive for exposure to methamphetamine, cannabis and heroin, she said.

In California’s Orange County, a case manager heard a mother screaming at her five children during a remote telephone session, prompting abuse concerns, said Essex.

She said the case manager was trying to help the woman create a structure for her family that would make things less stressful, but that it was hard to do in the best of cases, much less remotely.

“It’s a band-aid for this moment that we’re in,” she said.

(Reporting by Sharon Bernstein; editing by Bill Tarrant and Tom Brown)