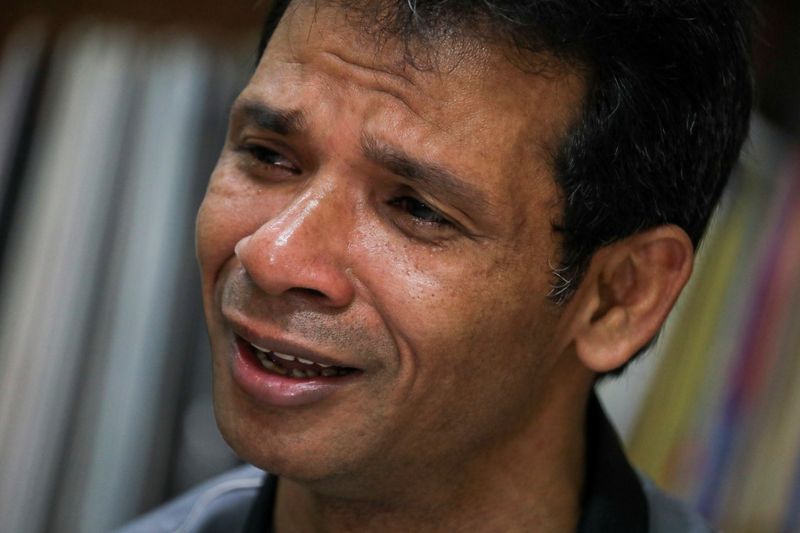

KUALA LUMPUR (Reuters) – Zafar Ahmad Abdul Ghani, a Rohingya Muslim refugee and activist who fled persecution and ethnic strife in Myanmar, has called Malaysia home for nearly three decades.

Now, it’s more like a prison.

Zafar, 51, has not left his home on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur for nearly a year, after misinformation spread online that he had demanded Malaysian citizenship, triggering a wave of hate speech and death threats against him and his family.

“I’m still scared. For a year, I’ve not set foot outside. I’ve not seen the earth outside,” said the father of three.

Zafar has reported the false accusations and online attacks to the police, but to his knowledge, no charges have been filed. He has denied making any demand for citizenship or the same rights as citizens for Rohingya in Malaysia.

More than 100,000 Rohingya live in Muslim-majority Malaysia, long seen as friendly to the persecuted minority even though they are not officially recognised as refugees.

The welcoming sentiment soured a year ago as people started saying Rohingya were spreading the then surging coronavirus.

Hate speech calling for violence against Rohingya and other undocumented migrants spread widely online. A significant portion of the volume targeted Zafar, who heads a prominent Rohingya refugee rights organisation.

Zafar still receives abusive calls and messages on his phone and social media accounts daily, and details and photos of his family have been circulated online, according to screenshots shown to Reuters.

His Malaysian wife, Maslina Abu Hassan, said the attacks have taken a heavy toll. Their children no longer attend school due to safety concerns, and last year, Zafar was diagnosed with depression and began taking medication to cope, she said.

Zafar, who is registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), applied to be moved to another country but his request was rejected after the agency said he did not meet its criteria for resettlement.

A UNHCR spokeswoman in Kuala Lumpur said in an email the agency could not comment on individual cases. Resettlement decisions depend on various factors, she said, but ultimately lie with any potential host countries.

Zafar said he hopes the agency will reconsider his case because he no longer feels safe in Malaysia.

“I cannot relax my body, my brain, my heart. I cry asking why people are doing this to me.”

(Reporting by Rozanna Latiff and Ebrahim Harris; Editing by Martin Petty and Tom Hogue)