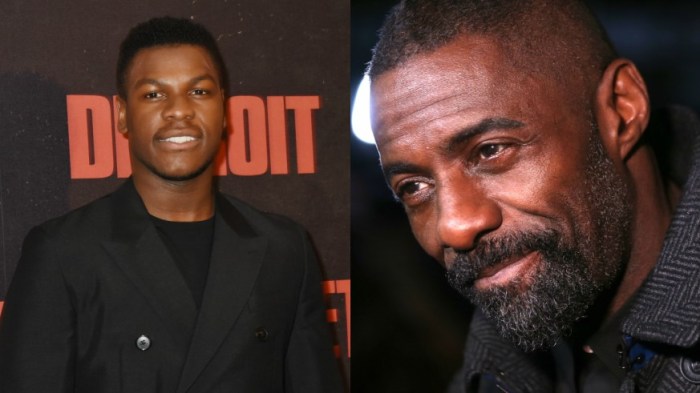

‘Detroit’

Director: Kathryn Bigelow

Stars: John Boyega, Algee Smith

Rating: R

4 (out of 5) Globes

“Detroit” begins jarringly; initially you may wonder if you wandered into the wrong theater. It opens with an expressionistic animated prologue, done in crayon colors, relaying the story so far: how Southern black people in the mid-20th century relocated up north in hopes of a better life, only to drive away the moneyed whites and find themselves living in squalor. It’s a perverse way to kick off a visceral, you-are-there docudrama, and a welcome one — a creative replacement for the dull opening text dumps you see even in a history film as original as “Dunkirk.”

But “Detroit”’s start does more than that. It tells us this isn’t only about mega-realism. Once the eye-popping opener is over, we’re plunged into the 1967 Detroit Riots, depicted with the usual shaycam madness seen in the previous two films by the tag team of director Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal (“The Hurt Locker,” “Zero Dark Thirty”). But thanks to the unique way they started their latest, we know to look beyond the herky-jerky camerawork and crash zooms on the surface, to see the artfulness and complexity among the chaos.

An uprising that lasted five days is too big a subject even for a 2 ½ hour film. So Bigelow/Boal focus on one of the more horrific stories buried under the rubble: the so-called “Algiers Motel Incident.” On the third day, 12 civilians — 10 black, two white — were tortured, physically and mentally, by white cops who suspected one of them of firing sniper shots at the National Guard from the window of the run-down motel. There was no sniper; the “rifle” had been a starter pistol, fired by one man, Carl Cooper (Jason Mitchell), looking to make a point about how black people live 24/7 under the threat of violence. It didn’t work. By the end of the night, three, including Cooper, would be dead, killed by cops who wouldn’t be convicted.

Needless to say, “Detroit” is scarily “timely” and “relevant.” But Bigelow/Boal don’t rest on their laurels. They don’t settle for a simple history lesson meant to speak to our own times, make us feel better by making us feel bad. “Detroit” won’t cause as much misguided debate as “Zero Dark Thirty,” a movie even some smart people (and a lot of dumb ones) mistook as a valentine to torture. It does, however, flirt with a structural gambit that could have backfired: They tell the story from both sides. They give the racist white cops — led by one David Senak, renamed Krauss and played by a terrifyingly confident Will Poulter — enough screentime that we can’t write them off as one-note baddies.

Still, don’t think that equal times means equal respect. “Detroit” doesn’t lapse into moral equivalence, suggesting everyone was too confused, too overwhelmed to do the right thing. The cops aren’t good people who did a bad thing. Krauss is introduced driving around the bombed-out hellscape of mid-riot Detroit, remarking that, “We’ve failed these people.” He doesn’t mean cops are in the wrong; if anything, he feels they haven’t been aggressive enough. Everybody has their reasons, but sometimes those reasons aren’t good.

When he arrives at the Algiers, Krauss is swaggering, electrified to be in charge. His ire exacerbated after catching one man (Anthony Mackie) on a bed with two young white girls (Hannah Murray and Kaitlyn Dever), Krauss ramps up his enhanced interrogation tactics. His favorite trick is taking one suspect into a room and pretending to kill them, thus freaking out the others. He treats this so-called “death game” as just that. “You want to kill one?” he asks one of his colleagues, as though he was asking them to shoot a beer can with a BB gun.

The Bigelow/Boal team is an odd one. They really are a tag team: Boal, obviously a former journalist, lays out the facts, which she films dutifully; in return, he gives her a few set pieces she can knock out of the park. The “incident,” which eats up about an hour of the middle, may be the greatest thing she’s ever made. Her handling of it is a lot like Barry Ackroyd’s cinematography: Handheld and anxious but stopping short of mere herky-jerky. You can always see what’s going on. As the camera pores over her the sweating faces of the uniformly excellent cast, what looks like chaos is all about control.

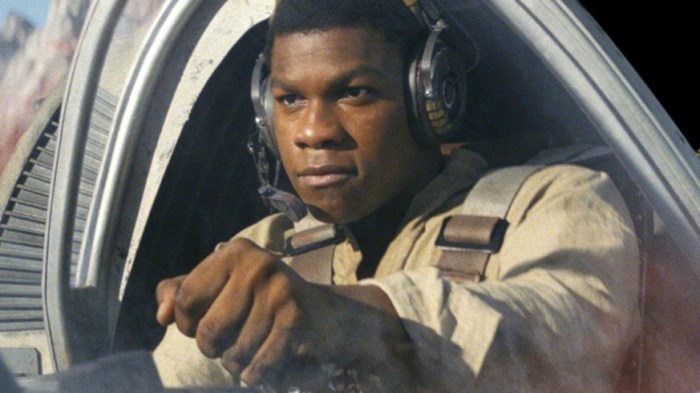

“Detroit” will make you angry and upset. You’ll feel like a witness — a lot like John Boyega’s security guard, who happens upon the scene and stays, hoping, wrongly, that the presence of a black authority figure will mollify the cops’ racial ire. He thinks if black people play by the rules, if they know how to talk to cops and not get on their bad side, all will be fine. And we know that doesn’t always work.

But “Detroit” isn’t only about rage. It’s about trauma. As the incident wears on, we see those involved finding an out and taking it, turning their back, escaping from a nightmare that’s only going to get worse. It starts with the National Guard, who realize what Krauss is doing and gingerly re-classify the investigation as a local matter, washing their hands of the matter. Even the victims can’t help but do step away, too. After they’ve been fake-shot during the “death game,” the fake-dead are released, allowed to run to safety, not looking back. When two others manage an escape, they want nothing but to hole up in another motel room and cry.

“Detroit” doesn’t blame them for turning their backs; it’s an all-too-human impulse to run, and it understands that their survivor’s guilt will only add to their already considerable PTSD. That’s really what “Detroit” is about. It’s a chance to highlight a heinous chapter in American race relations that still resonates 50 years out. But it’s also about bottling up that feeling of helplessness, that feeling that even someone who’s been through the worst of it can’t fix a dangerously broken system. “Detroit” won’t make us feel better about the world, but it will help us understand it.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge