‘Safe’ Julianne Moore was still an uneasy up-and-comer when she headlined Todd Haynes’1995 art-horror opus “Safe.” She stole parts of “The Hand That Rocks the Cradle” and went casually bottomless in “Short Cuts”; meanwhile her semi-awkward injections into “Nine Months” and “Assassins” were en route. But the world was not yet sure to make of her, and especially her film, when it showed up at Sundance. Part Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman,” part Val Lewton horror, but where the menace is not only not seen but actually invisible, it confounded audiences, only to later gain a passionate cult audience. In a sense it did its job too well: It’s such a creeper that it doesn’t penetrate the skin until a second viewing, at which point it never leaves. On its surface, “Safe” is lampooning two things: the upper-middle class suburban industrial complex and the diseases that haunted the 1980s. Moore is Carol White, a blank name for a woman so blank that her voice is permanently one notch above the ambiance of whatever room she’s in. (And the ambiance is loud, with Haynes cranking up the indiscriminate whirring — close to the sound city dwellers hear when they’re out in the country — as a means of freaking them out even when nothing appears to be going on.) Carol lives in a San Fernando McMansion with her corporate shark husband (Xander Berkeley), who is introduced grinding into her while she pats him on the back maternally. One day Carol starts feeling vaguely ill. Eventually she’s suffering freak nose bleeds, and following that is a seizure at a baby shower. What’s happening? It’s never explained. That doesn’t stop her from assigning it a cause anyway. Carol winds up doing some amateur sleuthing — what anti-vaccine folks would refer to today as attending “The University of Google” — and becomes convinced whatever ails her has to do with pollutants in the air, or at least all over her wealthy digs. The film’s second half relocates to a desert-adjacent camp that looks a lot like a cult, where nice denizens in unflattering sweaters hole themselves off from the rest of the world, listening to the low-key, paternal ramblings of a leader who looks like an insurance salesman (Peter Friedman, so subtly sinister that he practically disappears from the screen when he’s on it). He informs them a tune that would sound familiar to those suffering from another, major disease from 1987: that their illnesses are their fault. Haynes isn’t subtle about what he’s satirizing here, even if his film only drops the term “AIDS” once, and inside its funniest joke yet. (Friedman’s leader is said to be “a chemically sensitive man with AIDS, so his perspective is incredibly vast.”) And yet “Safe” is vague enough about what it’s really about that not only are all of interpretations valid, but it’s openness becomes discomfiting in and of itself. It’s a horror film about ideas and also about menace, where both are hard to define and parse. In the suburban first half, Haynes films entire scenes in Akerman-esque long take master shots, filmed from a distance with a scarily slow dolly-in. As Carol’s condition worsens, the viewer is forced to spend minutes scanning the shots for something, anything that could be causing her damage. When no solution presents itself, we can only conclude that the boogeyman is everything — her entire existence, every piece of luxury furniture, every ’80s outfit and ’do — and nothing. Everything in the film is designed to slowly work the senses, from Moore’s carefully sculpted, unbearably fragile performance on down to the film’s stealthily heartbreaking final zoom. It turns vagueness into the scariest thing you’ve ever experienced.

The Criterion Collection

$39.95

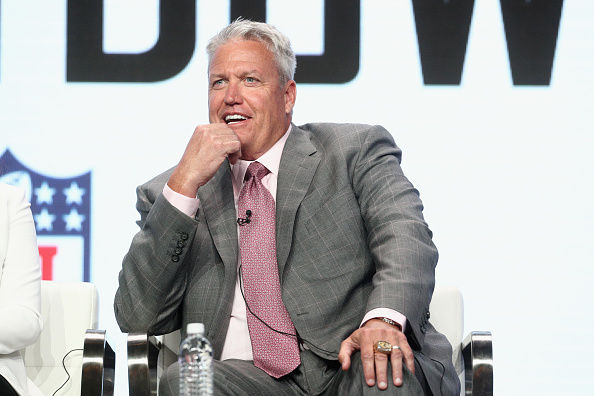

Disc Jockey: Julianne Moore gave one of her best performances in ‘Safe’

Criterion Collection

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge