Instead of helping steer minors out of the criminal justice system, one city agency is being scrutinized for allegedly putting children at risk by failing to take steps to guarantee services were provided correctly.

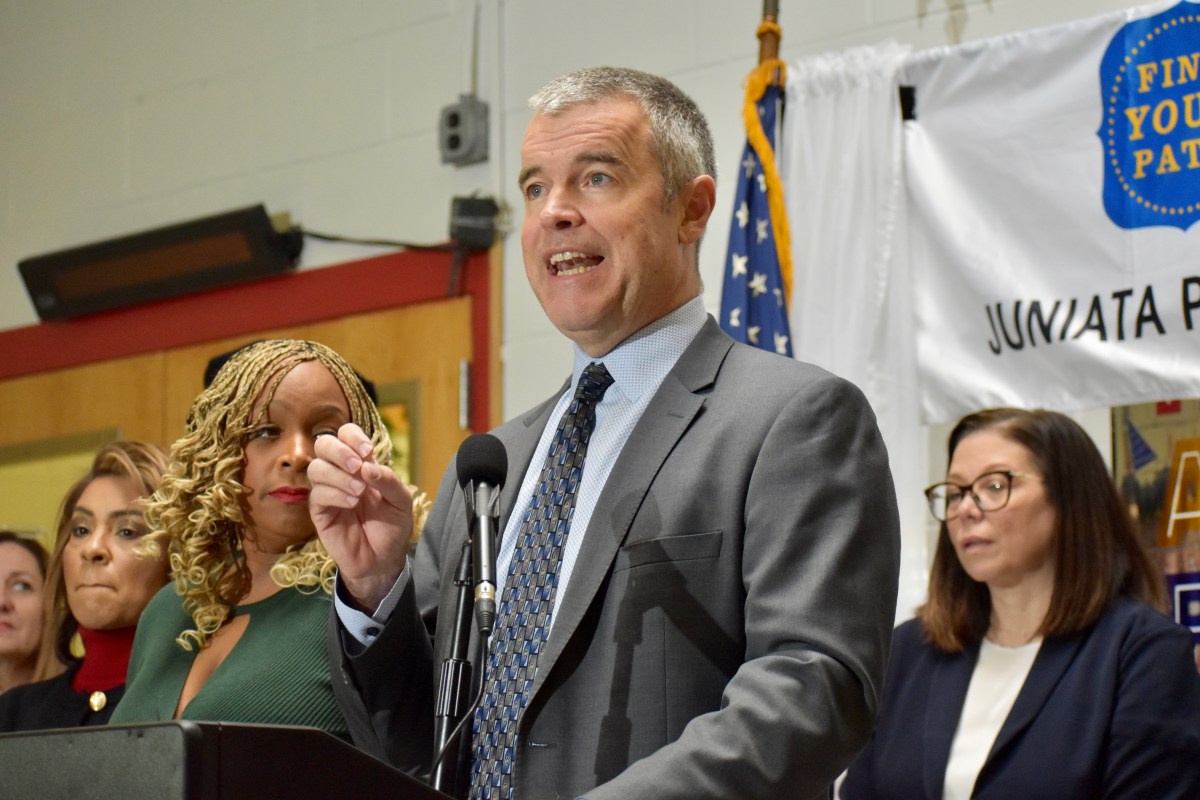

City Comptroller Scott Stringer released an audit on Friday that claims the city’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) — aimed at protecting and promoting safety and well-being of city children and families — did not follow up on its responsibility to make sure proper care and rehabilitation services were being provided to children through its Close to Home program.

RELATED:Thousands of seniors, disabled left stranded by MTA’s ‘Stress-A-Ride’ program: Comptroller

ACS launched the Close to Home juvenile justice program in 2012 in order to place children between 7 and 15 years old – who were deemed delinquent by Family Court, yet didn’t require incarderation – into residential care for rehabilitation.

Through the placement, the children are able to live in a home-like environment closer to their families and the program is expected to offer a smoother transition back into society.

However, although the program is aimed to offer a community-based path toward rehabilitation, a recent report by the Department of Investigation discovered significant safety and oversight issues by ACS with Close to Home providers — an issue the comptroller decided to examine “from top to bottom.”

“Every child in the Close To Home program deserves a chance to get back on the right track, but the Administration for Children’s Services mismanagement and hands-off approach to oversight is robbing them of that opportunity,” Stringer said.

ACS said Thursday that since the completion of Stringer’s audit a year ago, site inspections have been conducted to address safety and security concerns at each of the 27 non-secure placements. The city has also provided the Close to Home program with an additional $4 million and more staff is being hired.

Starting this year, ACS is also making a minimum of eight site visits each year to each site in the program, including four unannounced overnight visits per year.

“The safety of our young people — and communities — is paramount. The NYC Comptroller’s audit concluded in June 2015 and, over the past year, ACS has taken numerous steps to improve monitoring and oversight of Close to Home,” an ACS spokeswoman said. “We have added experienced staff to monitor the safety of programs, enlisted the NYPD to assess security at all Close to Home sites, and, since 2013, we have shut down three programs that were unable to adhere to our standards.”

Before being placed in the program, ACS evaluates the needs of a particular child and assigns them to either a Non-Secure or Limited Secure Placement residence, for a stay of about 6 or 7 months.

According to the audit, which examined ACS’ Non-Secure Placement vendor network during Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015, a total of 560 youths were transferred to the program and $94.9 million was spent to house them. Nine providers were contracted by the agency during that time to offer services at 32 sites in the city.

Once in the homes, children are required to receive a call from ACS, an in-person meeting with the agency, parents or guardians are supposed to meet with ACS, and there is supposed to be monthly meetings between the children and agency.

However, the audit found that out of a sample of nine children who were in the program for 83 months, only one child received an initial call; six out of nine in-person meetings took place; one parent or guardian meeting occurred; and ACS was not able to provide evidence that a third of mandatory monthly meetings happened.

“When ACS doesn’t bother to meet with children or contact their parents, they’re telling these kids they don’t matter, and giving up on them before they even have a chance to turn their lives around,” Stringer said.

Each site is also required to receive one announced and once unannounced visit per year during which the agency looks at security issues, reviews incident logs, and assesses how the program is working for the children.

The audit instead found that ACS does not track if and when a visit occurs, two-thirds of sites did not get unannounced visits in 2014 — with two sites not being visited at all that year — and during site visits, the agency allegedly did not properly assess the program.

RELATED:NYC opens support center for lawyers representing immigrants in criminal, family cases

The comptroller’s office made a total of 14 recommendation to ACS including periodically verifying that children in the program are receiving the required services; create a system to make sure staff at the site are conducting the mandatory visits; ensure that site visits actually assess if the youth and communities benefit from the program; and making sure that providers who are in need of change are effectively monitored.