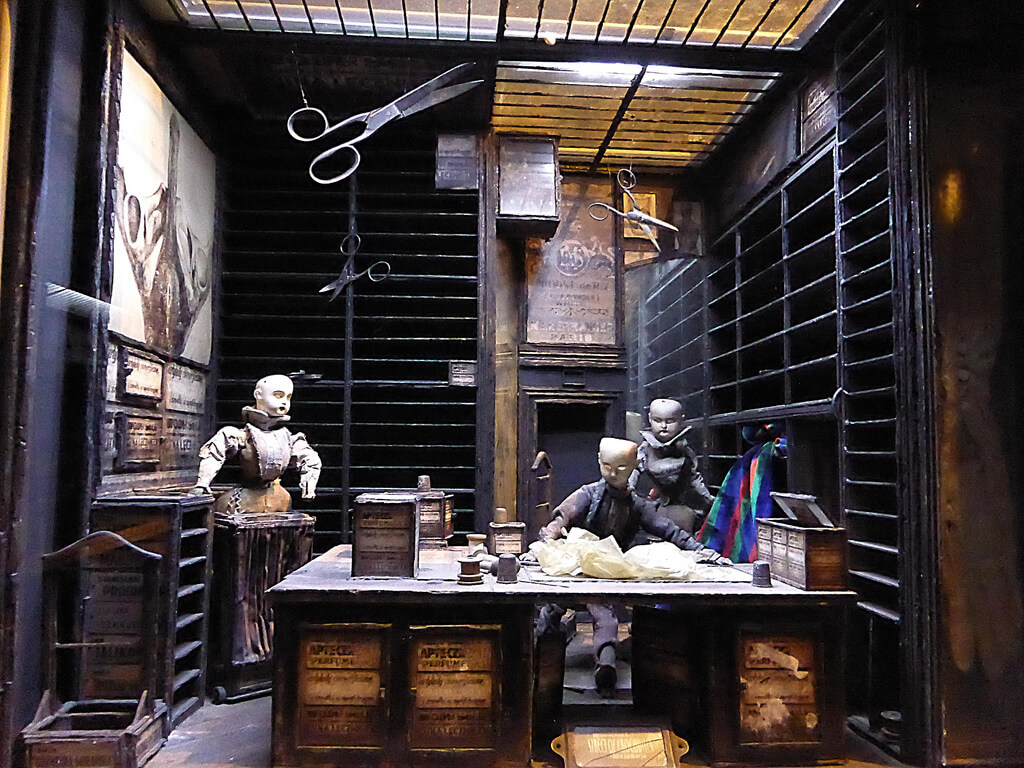

‘The Quay Brothers: Collected Short Films’ Christopher Nolan has done a noble deed: He’s used his considerable sway over fanboys to get them to at least consider watching some out-there avant-garde animation. Even if you don’t like the former Batman director’s work, you have to tip your hat to his recent shilling for Timothy and Stephen Quay, aka the Brothers Quay — masters of puppets and moods, whose reliably striking and unnerving work has long haunted the fringes of the mainstream. Occasionally the Quays have sneaked onto MTV — as in a segment of Peter Gabriel’s beloved “Sledgehammer” video — or simply inspired others. (Some assume they helmed Tool’s creepy, aggro videos, but they’re just knockoffs.) But more often than not they’re content to hang in their own remote domains, much as their creatures stew in shadowy zones, far away from the things of man. Classic Quays — like 1985’s “The Unnameable Little Broom (or the Epic of Gilgamesh)” and their most signature film, 1986’s “Street of Crocodiles” — show sad, forgotten objects rooting around in obscure, inscrutable worlds that teem with dust and grime and decay. They resist narrative, instead enveloping you in places from which it’s hard to escape, even when they end. RELATED: Interview: The Quay brothers on embracing digital Fifteen of their works make it into the new set “The Quay Brothers: Collected Short Films,” only the latest of many collections over the years, and the first to feature ruminative commentary tracks (on six of them) and some of their more recent movies. (It also features “Quay,” Nolan’s 10-minute doc, which hangs with them in their cluttered, musty studio loft.) The Quays were born in the Philadelphia region but moved to Europe in the ’70s, where they’ve stayed and where they’ve gained unplaceable Euro-American accents. (They returned in 2010 to make “Through the Weeping Glass,” about the most Quay place in the world: the Mutter Museum, the world’s premiere house for medical anomalies.) They’re between worlds, and so are their films. Every inch of each movie fetishizes all things Old Europe, from the aging and often broken objects (dolls, toys, knickknacks) that populate their work to a yen for writers like Bruno Schulz. Even the title fonts keep up the mood, often done as unreadable calligraphy that favors style over clarity. Along with digging into the films themselves, the new Quays set allows you to watch their evolution over time. They started off shooting on film, creating some of the most beautiful and rough textures in the movies. By the new century they were forced, thanks to monetary concerns, to switch to digital. You can see them, with films like 2003’s “The Phantom Museum,” trying to find similar-but-different looks while embracing the new-to-them technology. By 2010’s “Maska” they’ve found a way to get digital close to the presence of film stock. The film’s get longer too, though they don’t quite embrace clear storylines. They become longer soaks in worlds just as obscure and sinister, and even adopt, unlike their early work, narrators, who speak (usually in non-English languages, for extra-otherworldliness) about casting themselves into purgatories of their own devising. RELATED: Christopher Nolan made a short film about the Quay brothers The big favorites of the Quays remain the big draws, though, and with good reason. Many are menacing, vaguely melancholic wallows in pure weirdness, most famously “Street of Crocodiles,” with its legion of broken baby heads missing both eyes and the craniums. “Rehearsals for Extinct Anatomies” is the saddest: a black-and-white hang with diseased and sickly creatures, including one forever picking at a nasty head growth, made at the height of the AIDS scare. (Often deliberately out-of-focus, it looks like Jack Smith’s “Flaming Creatures” only stocked with people made of objects.) Sometimes the Quays have made doc-animation hybrids, the most fascinating being “Anamorphosis,” which looks at the titular kind of paintings, a kind of 2-D version of Magic Eye paintings where the image only reveals itself when you look at them from certain angles. Watching the set in one fowl swoop you not only gain a deeper, broader understanding of their work. You feel like feeling like one of their characters: willingly trapping one’s self in another realm from which you’d rather not leave.

Zeitgeist Films

$31.49

Christopher Nolan wants you to watch creepy Quay brothers movies

Zeitgeist Films

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge