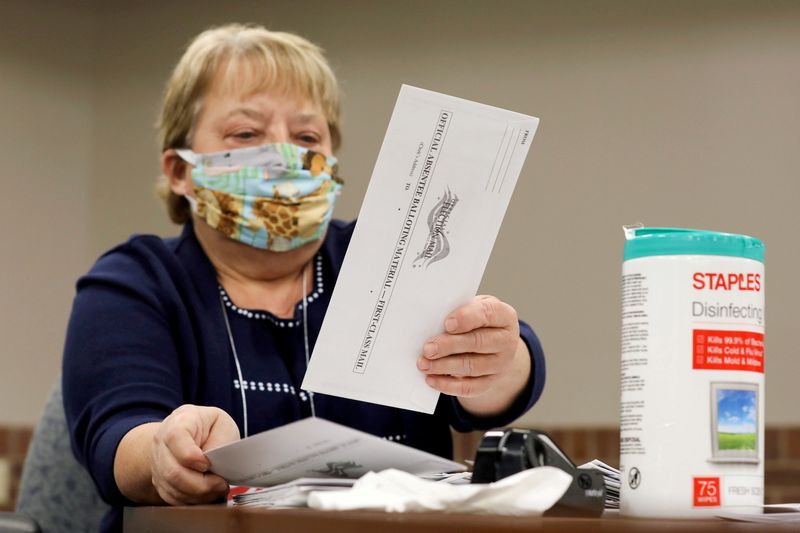

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – A Michigan town wants machines to speed up counting of absentee ballots. In Ohio, officials want to equip polling places so voters and poll workers feel safe from the coronavirus. Georgia officials, rattled by a chaotic election last month, want to send voters forms so they can request absentee ballots more easily.

In all three cases, the money is not there to make it happen, say local officials responsible for running elections in the states – any one of which could determine who wins the Nov. 3 presidential election.

Presidential nominating contests held this year in states from Wisconsin to Georgia have exposed massive challenges in conducting elections during the worst public health crisis in a century. Closed or understaffed polling venues led to long lines, there were problems delivering absentee ballots, and the votes took days, even weeks, to count.

But instead of receiving more money for the all-important contest between Republican President Donald Trump and Democrat Joe Biden, officials face budget cuts after tax revenues plunged in the virus-stricken economy, two dozen election officials across several battleground states told Reuters.

The consequences, they warn, go beyond practical headaches to the risk voters’ faith in the process will be undermined.

“What kind of price tag are you going to put on the integrity of the election process and the safety of those who work it and those who vote?” said Tina Barton, the city clerk and chief elections official in Rochester Hills, Michigan, a state where Trump beat Democrat Hillary Clinton in 2016 by fewer than 11,000 votes. “Those are the things at risk.”

This year’s nominating contests have shown that voting in the pandemic age costs more: Officials have to buy masks, face shields and other equipment to virus-proof polling places. They also must spend more to mail and count ballots.

Many officials say they don’t have the funding to do either job properly. Election experts say Americans are likely to vote in record numbers in November, when control of Congress will also be up for grabs along with state governorships and legislatures.

A funding shortfall could lead to “widespread disenfranchisement,” said Myrna Perez, director of the elections program at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, a non-partisan public policy institute. “We run the risk of people really questioning the legitimacy of the election.”

Congress approved $400 million in federal funding to help states hold the elections as part of the CARES Act coronavirus aid package passed in March – that’s just one-tenth of the $4 billion that experts at the Brennan Center have estimated will be needed this year to hold safe and fair elections during the pandemic.

Introducing a vote-by-mail system in new locales will require officials to pay for new paper ballots and thick security envelopes, and to buy expensive new machines to sort and tabulate them. Postage alone will cost nearly $600 million, the center estimated.

A fresh coronavirus aid bill passed in May in the Democratic-led House of Representatives includes $3.6 billion in new election funding for state and local governments. Some Republicans said they were open to considering more election funding, but opposed planned rules to make states boost mail-in voting, and the bill has no chance of passing the Republican-controlled Senate.

Trump and his Republican allies say mail voting is prone to fraud and favors Democrats, although independent studies have found little evidence of those claims. Democrats say efforts to discredit mail balloting, coupled with a possible fall in polling venues, could depress turnout.

Hans von Spakovsky, a former Republican member of the Federal Elections Commission who works at the conservative Heritage Foundation, said officials could cut costs by focusing on keeping polling places safe, rather than trying to ramp up voting by mail.

“I’m not saying that this is easy but it is not going to be as difficult as all these people are predicting,” von Spakovsky said.

(Graphic: Pandemic voting – https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/editorcharts/nmovajbxwpa/index.html)

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell declined to comment.

Amy Klobuchar, the senior Democrat on the Senate rules committee that oversees federal grants for elections, told Reuters money was so short that funds intended for election security, for instance, were being used to buy masks and cleaning supplies.

“That’s not a one-or-the-other choice. We need voters to be safe and we need our elections to be secure,” she said.

“EPIC FAILURE”

Some local governments are already squeezing election budgets, as cities across the country face a projected $360 billion revenue loss over the next three years due to the coronavirus outbreak.

Georgia sent absentee ballot requests to all voters ahead of its June 9 elections, which officials cited in local media estimated would cost at least $5 million. The program helped fuel record primary turnout in a state that has long been solidly Republican but which polls show could be competitive in November.

Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican, told state lawmakers late last month there was not enough money to do the same for November, and that the health crisis “has somewhat dissipated.” He instead will ask voters to request their ballot through a website. Raffensperger’s office declined to comment on the funding shortages, or on a rapid rise in COVID-19 cases in Georgia since then.

Most county governments in Georgia don’t have the money to send out requests themselves, said Deidre Holden, co-president of the state’s association of county election officials.

“If Congress doesn’t act we are going to see epic failure once again,” said Holden, an independent, who is also elections supervisor in Georgia’s Paulding County, a Republican-dominated suburb of Atlanta.

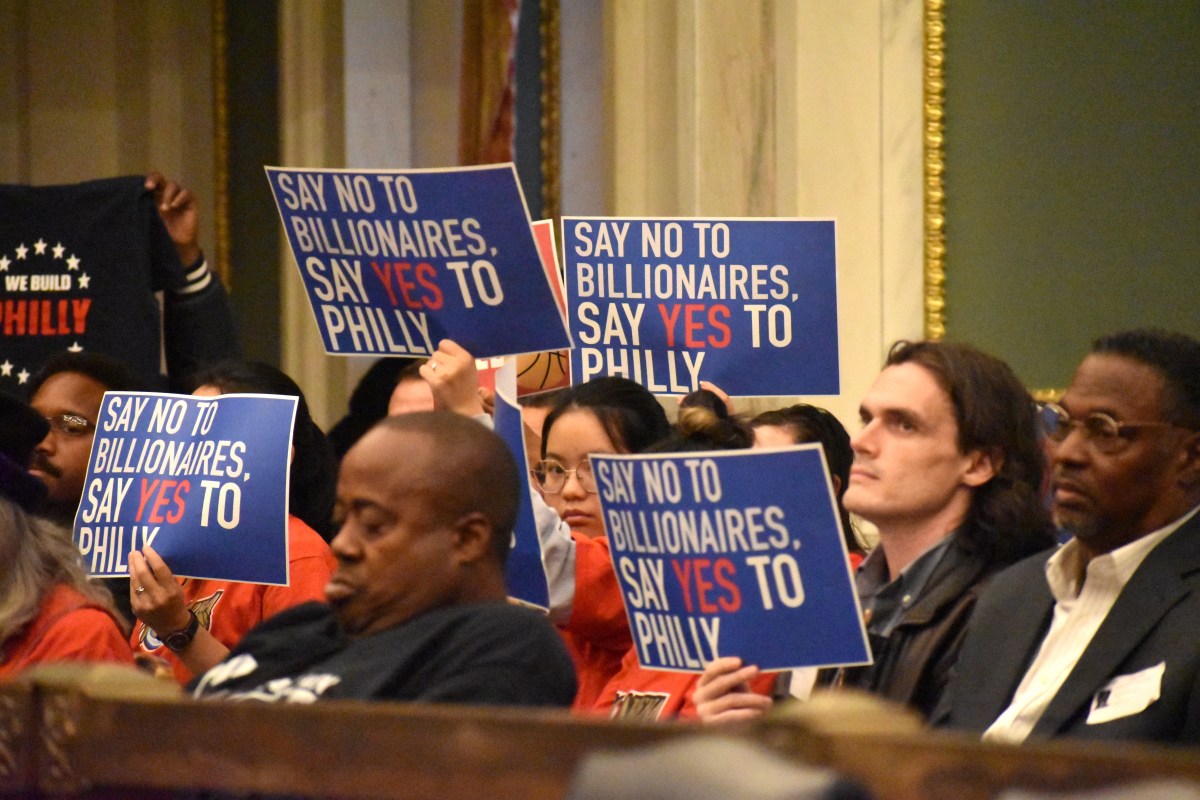

In Philadelphia, falling revenues have left an election budget of $12.3 million, instead of $22.5 million that officials proposed in early March. The city’s vote could be critical: Pennsylvania is a state where Trump won by less than a percentage point, and about a fifth of its registered Democrats live in Philadelphia.

The city expects about $750,000 in CARES Act grant money, but it already spent more than its expected grant holding its June 2 primary, its top election official, Commissioner Lisa Deeley, told Reuters.

LaVera Scott is director of elections for Ohio’s Lucas County, a Democratic-leaning area including Toledo in the battleground state that elected Democrat Barack Obama twice, but voted for Trump in 2016. Local officials asked her to cut her budget by 20%, and she has ruled out buying some safety equipment such as Plexiglas sneeze guards for more than 300 polling stations that the county hopes to operate.

“Feasibly, that’s not a cost that we can do here,” she said.

Scott also worries about not having enough staffing. Elderly polling workers are sending her apologetic greeting cards to say they won’t do the job this year for fear of catching the virus, she said.

RESULTS? “WHO KNOWS WHEN”

Voting rights advocates and election experts have been warning for months that a chaotic election could cause voters to question the results. Worse, if those results are delayed, a candidate could claim victory prematurely.

Without further federal funding, some election boards in Michigan won’t be able to buy new machines to count ballots faster, or cover all the postage costs of mail-in ballots, Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson told Reuters.

She told U.S. House lawmakers in June that the state needs $40 million from the federal government, far above the $11 million allocated to the state under CARES Act.

“This means … that election results may not be available until long after election night,” Benson, a Democrat, said in an emailed statement.

Michelle Anzaldi, the clerk for Michigan’s Pittsfield Charter Township, a suburb of Detroit, said her current vote-counting machines take between three and five seconds to count each ballot. A newer model can process more than 100 a minute but could cost more than $100,000.

With a budget crunch looming, the count will just have to wait.

“Instead of being tabulated by 10 p.m. at night, it could be who knows when,” she said.

(Reporting by Jason Lange and Simon Lewis, Additional reporting by Richard Cowan; Editing by Soyoung Kim and Sara Ledwith)