ZURICH/PARIS (Reuters) – European countries are still deciding if and when to inoculate children against COVID-19 amid questions around safety, supply and the desperate call for more vaccines from hard-hit regions around the world.

After a sluggish rollout, inoculation programmes for the continent’s adults 16 years and up are now underway.

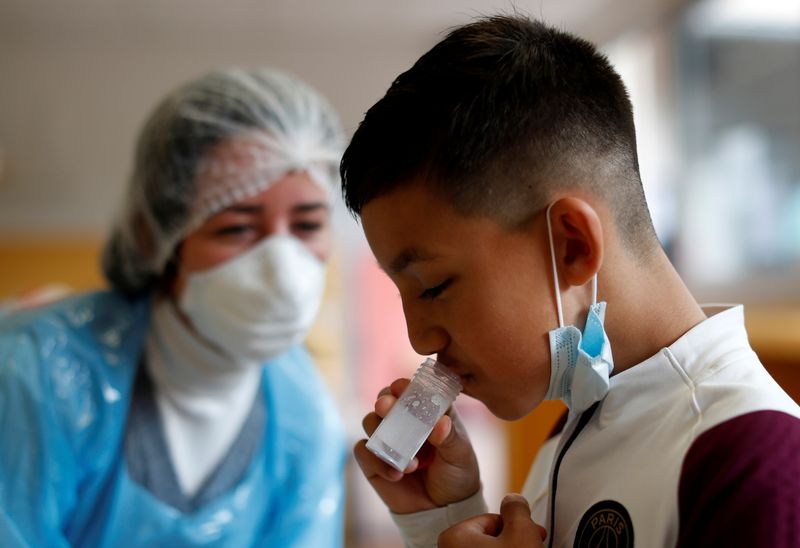

Adding children, who are less prone to severe COVID-19 but can be disease carriers, could help Europe to finally tame the pandemic.

Still, many health officials across Europe said they are continuing to weigh the low risk of serious COVID-19 disease among kids against the benefits for broader society that would accompany inoculating them.

“Individually, children and youth have less benefit from the vaccination than adults,” Norwegian Institute of Public Health infection control chief Geir Bukholm told Reuters.

“Vaccination to achieve herd immunity is also an aspect,” he added. “Should we recommend vaccination of children to gain control?”

In the United States, where more than 60% of adults have gotten at least one shot, 12- to 15-year olds started getting Pfizer/BioNTech shots this month.

Kids in Canada are getting shots, too.

The European Medicines Agency is still reviewing the Pfizer/ BioNTech for 12-to-15 year-olds, with Moderna planning to seek approval as early as next month.

In France, the reopening strategy likely must include vaccinating children, given its models require 90% of the population to get shots to avoid epidemic resurgence, its Institut Pasteur has said.

By May 20, however, only 18% of France’s adult population had received both shots of a coronavirus vaccine.

A source close to the French scientific committee that advises the government told Reuters its members are assessing several scenarios, including shots for 16-to-18 year-olds from June and younger children from September as the new school year starts.

“A clear answer from me is: ‘Maybe, and in any case, not now,” French Health Minister Olivier Veran said last week, when asked about vaccinating younger children.

“We need to get a shot to adults first.”

Italy could start by July, but the government is under pressure from a group of doctors and lawyers demanding a moratorium for children, due to what it calls a lack of long-term safety data.

“For children it is scientifically clear that there is no emergency,” Eugenio Serravalle, a pediatrician and president of the group, the Association of Health Studies and Information, told Reuters.

MORAL IMPERATIVES

Initial clinical trials of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in children showed them to be very effective at preventing COVID-19, and found no new safety concerns, beyond side effects documented in adults, most commonly headache, fatigue, body aches and chills.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is looking into reports that some young people have developed myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, after getting vaccinated.

In Switzerland, outside the European Union, federal officials hope to vaccinate 12- to 15-year olds starting this summer, pending regulatory approval.

While Britain’s speedy vaccination programme includes some 400,000 vaccinations daily and more than half of the population has been vaccinated, it has yet to decide on the under-16s, with the government saying it will be guided by the experts.

The prospect of children eventually rolling up their sleeves is already occupying thoughts of parents like Marie-Louise Pradin, a doctor in the northern French city of Lille with two boys, aged 11 and 14.

“The doctor in me tells me to go ahead, although I will admit the mother can’t help think: ‘What if…'” she said.

Meanwhile the World Health Organization has called for Western nations to delay vaccinating children and instead to donate doses to developing countries.

The low risk in children of suffering severe COVID-19 complications, combined with the desperate plight of nations like India struggling with fast-spreading variants and too little vaccine, mean there is a moral imperative for donations, said Georg Marckmann, a professor of medical ethics at Munich’s Ludwig Maxmilian University.

“There are good ethical reasons for Western countries to provide…vaccinations for low-income countries which have not been able to purchase sufficient dosages,” Marckmann said.

Still other experts counter that Western nations may be justified in inoculating their children before donating shots, as they aim for herd immunity and to eliminate excess deaths on the home front.

The virus has infected more than 32 million people and killed more than 712,000 in the 30-member European Economic Area (EEA).

Germany, where 13 percent of the adult population have received both doses of a vaccine, is debating now whether to give children from the age of 12 onwards shots from mid-June.

Its vaccine commission plans to make a decision in coming weeks.

“It must first be clarified exactly how urgently the children need the vaccination for their own health protection,” Chairman Thomas Mertens told German state radio on Tuesday.

“Our primary goal must be the protection and well-being of children.”

(Reporting by John Miller in Zurich, Matthias Blamont in Paris, Andreas Rinke and Maria Sheahan in Berlin, Emilio Parodi in Milan, Marine Stauss in Brussels, Tim Barsoe in Copenhagen, Essi Lehto in Helsinki, Terje Solsvik in Oslo, Alistair Smout in London, Gergely Szakacs in Budapest and Andrey Khalip in Lisbon; Editing by Josephine Mason and Raissa Kasolowsky)