(Reuters) – The U.S. government has been slow to approve licenses for American companies like Lam Research Corp and Applied Materials Inc to sell chipmaking equipment to China semiconductor giant SMIC, sources said, as the impact of a global chip shortage spreads.

Many licenses for U.S. suppliers to ship an estimated $5 billion dollars’ worth of equipment and materials have not come through, according to more than half a dozen industry sources, though numerous companies submitted applications soon after the Chinese company was blacklisted in December. Certain licenses have been granted, including for small numbers of expensive equipment in recent days.

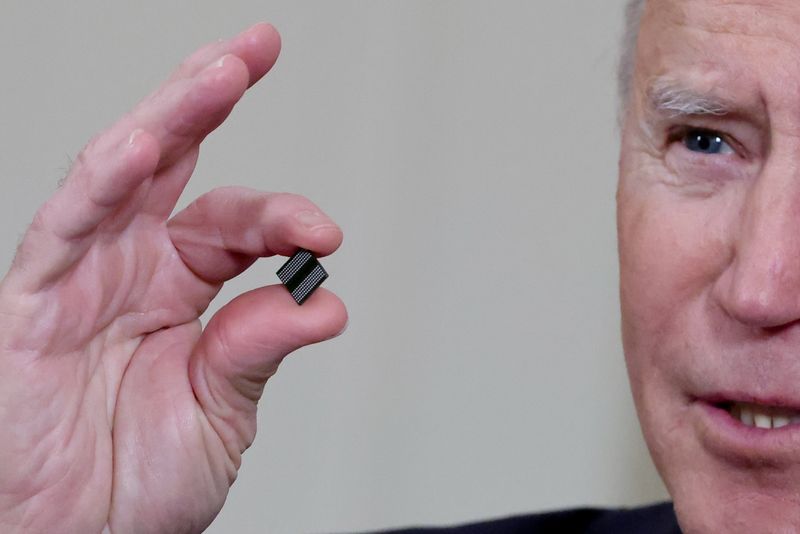

As policy shifts under President Joe Biden, who took over from Donald Trump in January, U.S. government agencies led by new appointees still have not completely decided what should be sold to Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp, which produces chips for Qualcomm Inc and other American companies.

The Trump administration placed SMIC on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s entity list over concerns of SMIC aiding China’s military.

The listing, which requires U.S. suppliers to obtain a license before shipping goods to SMIC, is unusual because it says most products should be granted on a case-by-case basis. However, equipment that can be used to make only the most advanced, 10-nanometer and smaller chips is likely to be denied licenses.

The administration is supposed to make decisions on license applications within a month, but follow-up questions stop the clock.

“Lam Research is still in the application process and has not yet received a response,” a Fremont, California, company spokeswoman said on Wednesday.

Applied Materials’ chief financial officer said in a Feb. 18 earnings call its forecast did not assume licenses would come through. A spokesman for the Santa Clara, California-based company declined further comment on the licenses this week.

SMIC did not respond to requests for comment, but the company has said it provides services solely for civilian and commercial end users and that it has no ties to the Chinese military.

Decisions on licenses have been held up as officials ask follow-up questions about applications in part to determine whether the parts or components could be diverted for use in producing items 10 nm or smaller, sources said.

Washington trade lawyer Giovanna Cinelli said many license applications have resulted in “a lot of back and forth, which has elongated the period of review.”

In a statement, a Commerce Department official dismissed the possibility that curbs on SMIC could contribute to the chip shortage, noting that the shortfall was tied to older technologies while SMIC restrictions relate to leading-edge technology. The statement did not address the potential impact of delays in licenses for older technology.

SMIC, the largest foundry in mainland China, is an important player in the global semiconductor supply chain, which is under pressure as pandemic lockdowns drive up demand for electronics such as laptops and phones. Last month, it said it could not meet customer demands for certain technologies and its plants have been running “fully loaded” for several quarters.

SMIC’s technological capabilities lag far behind cutting-edge foundries like industry leader Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co, according to industry sources.

Companies like Applied Materials and Lam Research, two key suppliers of production equipment, submitted numerous license applications to sell to the company. The bulk have not yet been acted on, industry sources said.

A spokeswoman for Entegris Inc, an advanced materials supplier, said the Massachusetts-based company had submitted 10 applications to sell to SMIC and received its first license in the past week.

Other companies that ship to SMIC include California’s KLA Corp and Massachusetts-based Axcelis Technologies Inc . A KLA spokeswoman declined to comment on any licenses and, while Axcelis’ CEO spoke of “uncertainty” related to its licenses on Feb. 11, a company spokeswoman declined to provide an update.

Cymer, a San Diego company that makes deep ultraviolet light sources, is also among suppliers that need licenses to send parts to SMIC. A spokeswoman for ASML, the Dutch chip equipment maker that owns Cymer, declined to comment on the licenses, saying she could not discuss customer-specific information.

Qualcomm, which uses the Chinese foundry to produce chips with decades-old technology, put in applications for tools SMIC needs to produce the chips, just in case equipment makers do not get their licenses for the tools, an industry source said. But they have not come through yet, the source added.

In September, SEMI, a worldwide industry group, said in a draft letter seen by Reuters that SMIC accounts for as much as $5 billion in annual U.S. sales.

(Reporting by Karen Freifeld and Alexandra Alper in Washington; Editing by Chris Sanders, Shri Navaratnam and Matthew Lewis)