(This Oct. 13 story corrects to show that the federal government, not Eli Lilly, made the decision to pause a clinical trial of the company’s antibody drug, paragraph 10)

(Reuters) – U.S. drug inspectors uncovered serious quality control problems at an Eli Lilly and Co <LLY.N> pharmaceutical plant that is ramping up to manufacture one of two promising COVID-19 drugs touted by President Trump as “a cure” for the disease, according to government documents and three sources familiar with the matter.

The Lilly antibody therapy, which is experimental and not yet approved by regulators as safe and effective, is similar to a drug from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals <REGN.O> that was given to the president during his bout with COVID-19.

Trump, who credits the Regeneron drug with speeding his recovery, has called for both therapies to become available immediately on an emergency basis, raising expectations among some scientists and policy experts that the administration will imminently release an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the drug. The president’s push is key to his efforts to convince voters he has an answer to the pandemic that has killed more than 215,000 Americans.

But the findings by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration inspectors at the Lilly manufacturing facility, which have not been disclosed previously, could complicate the drugmaker’s bid for an EUA from the federal agency, two of the sources and two outside legal experts told Reuters. That’s because U.S. law generally requires compliance with manufacturing standards for authorization of a drug.

The three sources who spoke to Reuters requested that their names be withheld so they could speak freely without fear of retaliation.

Inspectors who visited the Lilly plant in Branchburg, New Jersey, last November found that data on the plant’s various manufacturing processes had been deleted and not appropriately audited, government inspection documents show.

“The deleted incidents and related audit trail were not reviewed by the quality unit,” the FDA inspectors wrote. Because the government inspection documents reviewed by Reuters were heavily redacted by the FDA it was not possible to see the inspectors’ more specific findings.

Following its November inspection, the FDA classified the problems as the most serious level of violation, resulting in an “Official Action Indicated” (OAI) notice.

That “means that the violations are serious enough and have a significant enough impact on the public health that something needs to be fixed,” said Patricia Zettler, a former associate chief counsel at the FDA who is now a law professor at Ohio State University.

Separately, Lilly said this week that the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases paused a government-backed clinical trial of its COVID-19 drug in hospitalized patients “out of an abundance of caution” over a potential safety concern. The company said it supported the decision. It did not release information on what the problem was and declined to say how the news might affect their EUA request.

In response to Reuters’ questions on Monday about the manufacturing issues, Lilly confirmed the OAI notice but declined to provide details on what prompted the FDA action. The drugmaker said it has launched a “comprehensive remediation plan,” has increased staffing at the site and was working “aggressively” to address all concerns raised during the inspection.

The data deletions cited by the FDA, Lilly said, were not related to production of the drug.

“These findings do not impact product quality or patient safety, as outlined in a detailed assessment submitted to FDA,” the company’s statement said. “Lilly continues to provide updates to the FDA on progress towards completion of our detailed plan.”

The drugmaker declined to provide a copy of the assessment it gave the FDA.

The FDA did not respond to requests for comment. The White House declined to comment.

One of the sources told Reuters that Lilly employees had complained about problems at the plant, including insufficient staffing and falsified records tracking whether workers had followed FDA manufacturing standards.

Lilly said the FDA has not made any findings of falsification at the site.

Out of 563 total inspections concluded in fiscal year 2019 by the FDA across the country, only a small fraction resulted in the most serious OAI classification, FDA data shows, and no other Lilly facility has received such a notice in at least 10 years.

None of Regeneron’s facilities have received OAIs based on inspections through the end of October 2019, FDA records show. Regeneron said in a statement it was “proud” of the company’s efforts to comply with manufacturing requirements, which “is reflected in our FDA inspection record.”

Lilly has not disclosed the FDA inspections in its U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings. U.S. courts, in cases involving other companies, have ruled that such information could be material to investors. But that depends on several factors, including the severity of the FDA’s findings, as well as whether the company has failed to correct the deficiencies.

In its statement to Reuters, Lilly did not respond to a question about why the inspections weren’t disclosed.

PROMISE AND PITFALLS

Trump had previously focused on a promise to deliver a coronavirus vaccine by the Nov. 3 election, but that effort has since lost momentum due to doubts that any drugmaker will have enough proof of safety and efficacy in the coming weeks.

Now under increased pressure to act swiftly against the pandemic, the FDA has discretion to approve Lilly’s COVID-19 therapy for emergency use even if the manufacturing issues have not been fully resolved.

The FDA has already been criticized by some scientists and politicians for issuing EUAs for use of anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma treatment in coronavirus patients, despite little or problematic data. The agency ultimately withdrew its authorization for hydroxychloroquine and the plasma authorization remains in place.

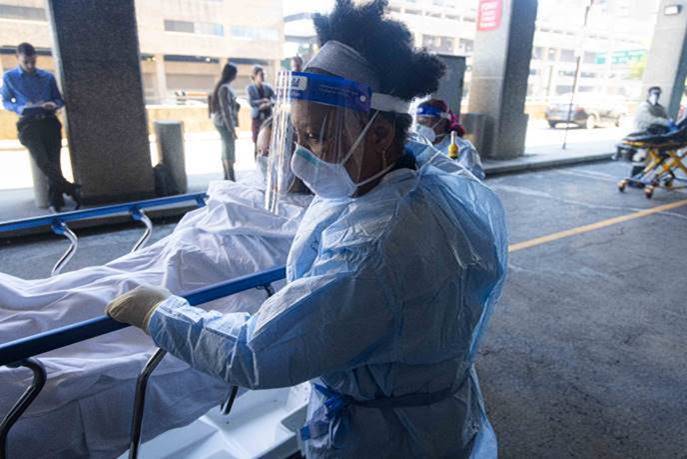

The Branchburg plant specializes in a range of drugs that are injected by syringe or infused intravenously. Partly because of the risk of contamination, such treatments are more complex to make than conventional pills and require additional vigilance to ensure quality and safety, pharmaceutical experts say.

Lilly’s drug, known as LY-CoV555, is a manufactured copy of an antibody from a patient who recovered from COVID-19. Known as monoclonal antibodies, such treatments work by recognizing and locking onto foreign invaders to block infection of healthy cells.

Leading scientists have pointed to antibody drugs as a promising way to treat people who are already sick, and also to temporarily prevent infection in people at high risk of COVID-19, until a successful vaccine is identified.

Lilly’s clinical trial data thus far show its therapy may help reduce hospital stays and emergency room visits for COVID-19 patients. The company has asked U.S. regulators to approve emergency use of the drug for higher-risk patients who have been recently diagnosed with mild to moderate coronavirus.

Antibody drugs for the coronavirus are very limited in number, but Lilly says it expects to produce around one million doses of the treatment by the end of this year.

The Trump administration’s program to accelerate development of COVID-19 vaccines and therapies, dubbed Operation Warp Speed, has already reached a $450 million deal with Regeneron for up to 300,000 treatment doses of its antibody treatment, REGN-COV2.

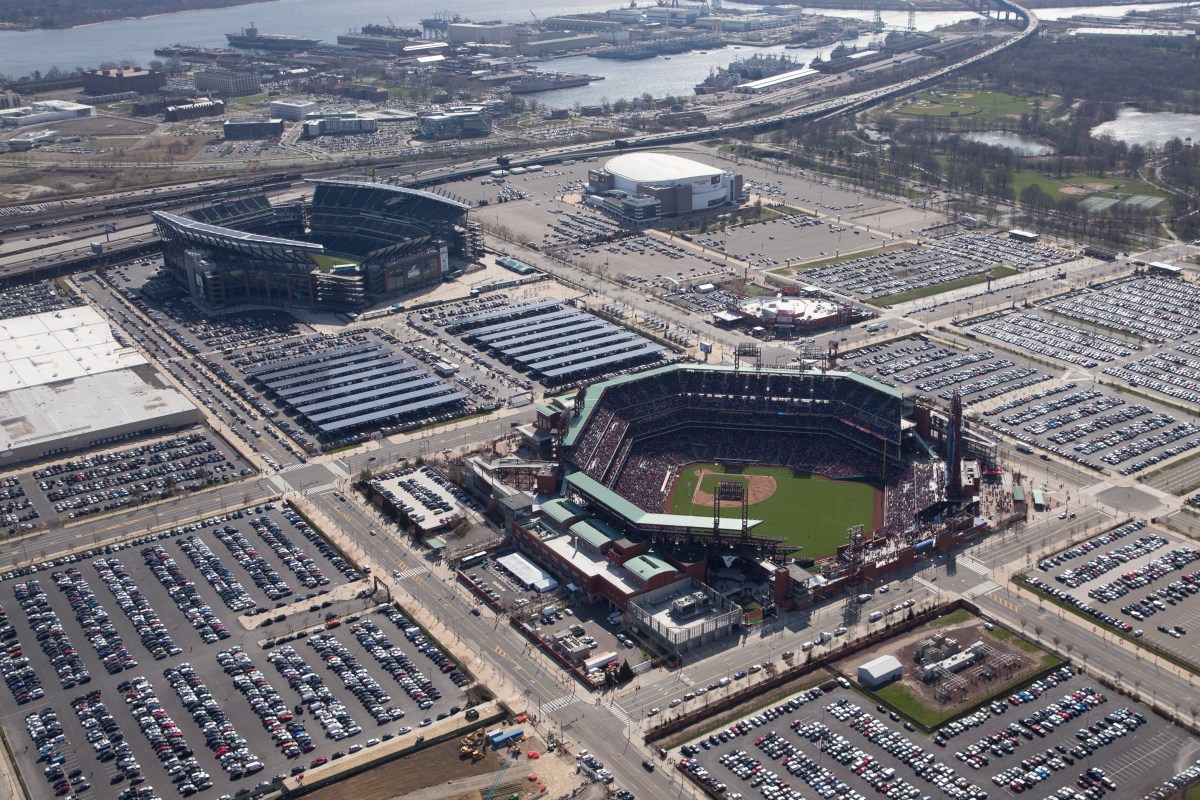

No such agreement has been reached with Lilly, but the government’s interest in its therapy appears keen. Earlier this month, Warp Speed officials traveled to Branchburg to meet with Lilly executives, according to two sources briefed on the visit. Among the attendees were Lilly Chief Executive David Ricks and Chief Science Officer Dan Skovronsky, one source said.

A potential complication is the former relationship between Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar and Lilly, where he held a high-level position until 2017. Generally, he would have to sign off on a waiver for any company seeking an EUA that had been cited by the FDA for manufacturing problems. But because he is a former Lilly executive, Azar’s involvement in the deliberations could pose a potential conflict of interest, legal experts said.

An HHS spokeswoman said Azar is not prohibited from participating in the deliberations about Lilly’s manufacturing issues or its EUA. But she said that in general, Azar has delegated his emergency authorization powers to the FDA.

HHS did not make Azar available for comment.

PRESSURE TO ACT

Lilly acquired the New Jersey site when it bought ImClone Systems in 2008, and over the next ten years the FDA inspected the facility several times and found no serious problems.

That changed last November.

Two inspectors spent ten days at the facility, according to the redacted copy of their report, known as a “483 letter”, which was reviewed by Reuters. The FDA inspectors described problems with “appropriate controls over computers and production systems,” and noted that data had been “deleted” and went unreviewed by company auditors.

After the November 2019 inspection, the FDA returned to the Lilly site for a follow up audit and found additional problems in August, issuing a second 483 letter, according to an FDA inspection log.

Among the problems: Lilly did not always have proper laboratory controls for drugs manufactured at the plant, the November inspection report said. One source said, for instance, that the plant failed to maintain systems meant to ensure that a popular anti-migraine drug, Emgality, met strength and purity standards.

If the issues aren’t fixed, then the FDA could escalate the matter by issuing a warning letter, which sets out a deadline for correcting the problems. Ultimately, the FDA could order a company to cease producing certain drugs at a facility.

Lilly said it had not received a warning letter.

Meanwhile, Trump is leaning on the FDA for a quick approval of the antibody drugs. He does not have the authority to issue an EUA under the law.

However, he said in a video last week “I have emergency use authorization all set. And we’ve got to get it signed now.”

(Marisa Taylor reported from Washington D.C. and Dan Levine from San Francisco. Editing by Michele Gershberg and Julie Marquis)