BERLIN (Reuters) – Germany should not drop support for the planned Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Russia over the crackdown on Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny, as “feel-good moralising” is not foreign policy, the man best placed to be the next German chancellor told Reuters.

Pointing to U.S. purchases of crude oil from Russia, Armin Laschet described himself as a political realist – or “Realpolitiker” – and said: “We have to take the world as it is in order to make it better.”

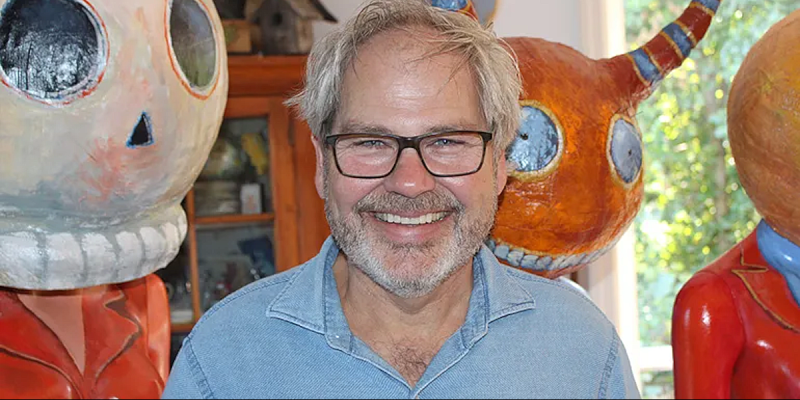

Laschet, who last month won an election to the leadership of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU), said both values and interests were important in diplomacy.

“But feel-good moralising and domestic slogans are not foreign policy,” Laschet, who is premier of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, said in an interview that focused on understanding his little-known views on international affairs.

Laschet’s election to the CDU chair makes him the frontrunner to take over as chancellor from Merkel, who after 15 years in office has said she will not seek a fifth term following September elections.

Asked directly whether Germany should change course and renounce the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline, Laschet replied: “For 50 years, even in the aggressive times of the Cold War, Germany has bought gas from the Soviet Union, now from Russia. The German government is following the right course.”

Germany is facing growing pressure to repudiate Nord Stream 2 over the Navalny affair: at home, from the ecologist Greens – potential coalition partners for Laschet’s CDU – and abroad from the United States, and much of Europe.

Navalny, sentenced on Tuesday to 3-1/2 years in jail after a Moscow court ruled he had violated the terms of his parole, was arrested on Jan. 17 after returning to Russia from Germany where he was treated for poisoning with a military-grade nerve agent.

Moscow has accused the West of hysteria and double standards over Navalny and told it to stay out of its internal affairs.

Laschet stressed that he had criticised the attack on Navalny and his imprisonment, and also supported European Union sanctions against Russia over the Ukraine crisis.

“We must guarantee Ukraine’s geopolitical interests and secure our energy supply through this private-sector project,” he said of Nord Stream 2.

The project, set to launch this year, has split the EU, with some members saying it will undermine traditional gas transit state Ukraine and deepen the EU’s energy reliance on Russia.

Germany’s ecologist Greens, the most likely coalition partner for the CDU and its Bavarian sister party after September’s elections, have doubled down on their opposition to the pipeline following the Navalny affair.

Laschet did not believe these differences would be a coalition deal breaker. “I don’t think Nord Stream 2 will be a big election issue. Moreover, I think consensus with the Greens, for example, is possible.”

Laschet viewed Germany as “deeply anchored in the West” and saw the United States as “our closest non-European partner”. As for China, Germany must criticise its human rights violations, he said. “But at the same time, we trade with China.”

EURO BONDS, DEBT BRAKE

On Europe, Western Balkan states should retain the prospect of EU accession if they fulfil the entry criteria, Laschet said, adding: “Turkey is unfortunately moving further and further away from the rule of law principles of the European Union.”

He opposed introducing jointly issued debt, also known as euro bonds – a policy option some EU countries want to become a permanent tool after the bloc resorted to it to fund economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

“I don’t see euro bonds. And with regard to the EU Commission’s borrowing, I say: this is now a one-time thing for six years,” Laschet said in a nod to taxpayers who don’t want Europe’s biggest economy necessarily on the hook for any bailouts to more financially challenged member states.

On fiscal policy, Laschet rejected a proposal from Merkel’s chief of staff to soften Germany’s debt issuance law, allowing continued deficit spending, on grounds Berlin would be unable to stick to strict borrowing limits for several more years.

“The rules are good. The mechanisms contain the necessary flexibility – both the (EU’s 1992) Maastricht Treaty and the debt brake of our Basic Law,” Laschet said.

(Writing by Paul Carrel; Editing by Mark Heinrich)