(Reuters) – Personalized smart guns, which can be fired only by verified users, may finally become available to U.S. consumers after two decades of questions about reliability and concerns they will usher in a new wave of government regulation.

Four-year-old LodeStar Works on Friday unveiled its 9mm smart handgun for shareholders and investors in Boise, Idaho. And a Kansas company, SmartGunz LLC, says law enforcement agents are beta testing its product, a similar but simpler model.

Both companies hope to have a product commercially available this year.

LodeStar co-founder Gareth Glaser said he was inspired after hearing one too many stories about children shot while playing with an unattended gun. Smart guns could stop such tragedies by using technology to authenticate a user’s identity and disable the gun should anyone else try to fire it.

They could also reduce suicides, render lost or stolen guns useless, and offer safety for police officers and jail guards who fear gun grabs.

But attempts to develop smart guns have stalled: Smith & Wesson got hit with a boycott, a German company’s product was hacked, and a New Jersey law aimed at promoting smart guns has raised the wrath of defenders of the Second Amendment.

The LodeStar gun, aimed at first-time buyers, would retail for $895.

The test-firing of the LodeStar gun before Reuters cameras has not been reported elsewhere. A range officer fired the weapon, a third-generation prototype, in its different settings without issue.

Glaser acknowledged there will be additional challenges to large-scale manufacturing, but expressed confidence that after years of trial and error the technology was advanced enough and the microelectronics inside the gun are well-protected.

“We finally feel like we’re at the point where … let’s go public,” Glaser said. “We’re there.”

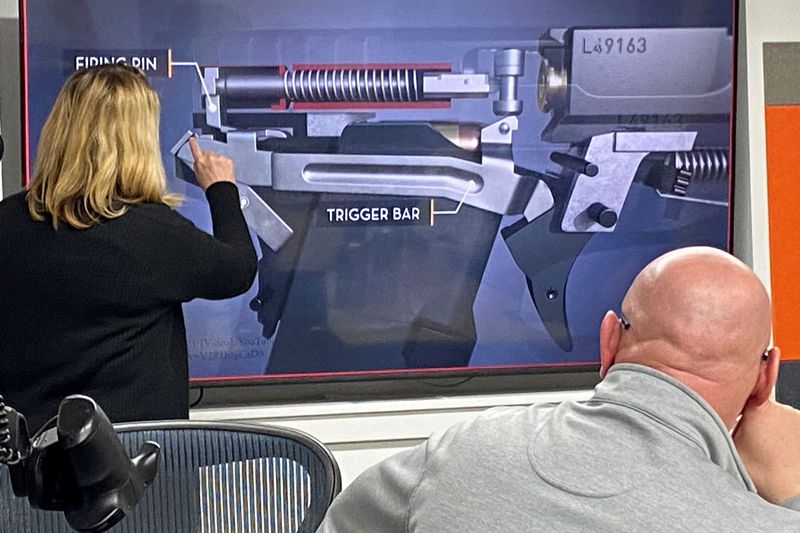

Most early smart gun prototypes used either fingerprint unlocking or radio frequency identification technology that enables the gun to fire only when a chip in the gun communicates with another chip worn by the user in a ring or bracelet.

LodeStar integrated both a fingerprint reader and a near-field communication chip activated by a phone app, plus a PIN pad. The gun can be authorized for more than one user.

The fingerprint reader unlocks the gun in microseconds, but since it may not work when wet or in other adverse conditions, the PIN pad is there as a backup. LodeStar did not demonstrate the near-field communication signal, but it would act as a secondary backup, enabling the gun as quickly as users can open the app on their phones.

SmartGunz would not say which law enforcement agencies are testing its weapons, which are secured by radio frequency identification. SmartGunz developed a model selling at $1,795 for law enforcement and $2,195 for civilians, said Tom Holland, a Kansas Democratic state senator who co-founded the company in 2020.

Colorado-based Biofire is developing a smart gun with a fingerprint reader.

Skeptics have argued that smart guns are too risky for a person trying to protect a home or family during a crisis, or for police in the field.

The National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), the firearms industry trade association, says it does not oppose smart guns as long as the government doesn’t mandate their sale.

“If I had a nickel for every time in my career I heard somebody say they’re about to bring us a so-called smart gun on the market, I’d probably be retired now,” said Lawrence Keane, senior vice president of the NSSF.

Guns coming to market could trigger a 2019 New Jersey law requiring all gun shops in the state to offer smart guns after they become available. The 2019 law replaced a 2002 law that would have banned the sale of any handgun except smart guns.

“The other side tipped their hand because they used smart guns to ban everything that’s not a smart gun,” said Scott Bach, executive director of the Association of New Jersey Rifle & Pistol Clubs. “It woke gun owners up.”

When Smith & Wesson pledged in 1999 to promote smart gun development, among other gun safety measures in an agreement with the U.S. government, the National Rifle Association sponsored a boycott that led to a drop in revenue.

In 2014, German company Armatix put a smart .22 caliber pistol on the market, but it was pulled from stores after hackers discovered a way to remotely jam the gun’s radio signals and, using magnets, fire the gun when it should have been locked.

(Reporting by Daniel Trotta; Editing by Donna Bryson and Leslie Adler)