President Donald Trump on Wednesday granted pardons to his former campaign chairman Paul Manafort and former adviser Roger Stone, sweeping away the most important convictions from U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 presidential campaign.

So far, Trump, who has 27 days left in the White House until President-elect Joe Biden is sworn in on Jan. 20, has issued 70 pardons since taking office.

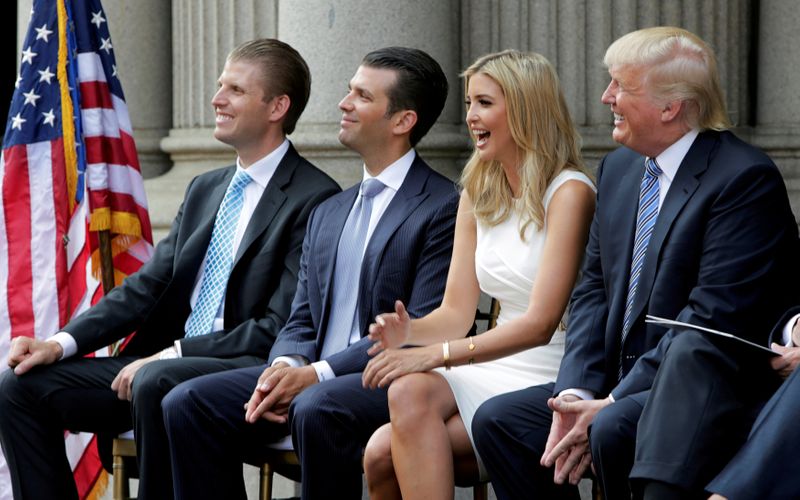

The New York Times reported earlier this month that Trump had talked with his personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani about pardoning him, citing two people briefed on the matter. The Times also said that Trump has asked advisers about the possibility of “preemptively” pardoning his three eldest children – Donald Trump Jr., Eric Trump and Ivanka Trump.

In 2018, Trump even said he had the “absolute right” to pardon himself – a claim many constitutional law scholars dispute.

Here is an overview of Trump’s pardon power.

CAN A PARDON BE PREEMPTIVE?

Yes.

Most pardons are issued to people who have been prosecuted and sentenced. But pardons can cover conduct that has not resulted in legal proceedings, though they cannot apply to future conduct.

The Supreme Court said in 1866 that the pardon power “extends to every offense known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment.”

Most famously, former President Richard Nixon was preemptively pardoned by his successor Gerald Ford in 1974 for all crimes he might have committed against the United States while he was in office.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter preemptively pardoned hundreds of thousands of “draft dodgers” who avoided a government-imposed obligation to serve in the Vietnam War.

ARE THERE LIMITS ON A PRESIDENT’S PARDON POWER?

The pardon power, which comes from the U.S. Constitution, is one of the broadest available to a president. The nation’s founders saw the pardon power as a way to show mercy and serve the public good.

The president does not have to give a reason for issuing a pardon. In a 1981 case, the Supreme Court said pardons “are rarely, if ever, appropriate subjects for judicial review.”

The pardon power, however, is not absolute. Crucially, a pardon only applies to federal crimes.

COULD TRUMP PARDON HIS CHILDREN AND INNER CIRCLE?

It would be legal for Trump to pardon his inner circle, including members of his family.

In 2001, former President Bill Clinton pardoned his brother, Roger, who was convicted for cocaine possession in Arkansas.

Clinton pardoned about 450 people, including a Democratic Party donor, Marc Rich, who had earlier fled the country because of tax evasion charges.

HOW BROADLY WORDED CAN A PARDON BE?

It’s unclear.

The pardon Nixon received from Ford was very broad, absolving Nixon for all criminal offenses he committed or may have taken part in during his presidency.

The U.S. Supreme Court has never ruled on whether such a broad pardon is lawful. Some scholars have argued the nation’s founders intended for pardons to be specific, and that there is an implied limit on their scope.

WHAT WOULD TRUMP PARDON HIS CHILDREN OR GIULIANI FOR?

Trump’s children have not been accused of any criminal wrongdoing, and it is unclear what Trump would pardon them for.

Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, who enforces New York state laws, has been conducting a criminal investigation into Trump and his family company, the Trump Organization. Vance, a Democrat, has suggested in court filings that his probe could focus on bank, tax and insurance fraud, as well as falsification of business records.

It is unclear what stage the investigation is at. No one has been charged with wrongdoing.

Trump, a Republican, has called the Vance probe politically motivated harassment. A presidential pardon, which can only be granted for federal crimes, would not apply to this investigation.

Giuliani’s potential criminal exposure is unclear. Federal prosecutors in Manhattan have been investigating his business dealings in Ukraine. Giuliani has denied wrongdoing and denied that he spoke to Trump about a pardon.

“Never had the discussion they falsely attribute to an anonymous source,” Giuliani said on Twitter on Dec. 1, referring to the New York Times report.

CAN PARDON RECIPIENTS “PLEAD THE FIFTH”?

Under the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, individuals can decline to speak to investigators if doing so might lead to self-incrimination. If someone receives a pardon and no longer faces legal jeopardy on the federal level, it may make it more difficult for them to assert this constitutional right.

However, since a presidential pardon applies only to federal crimes, pardon recipients can still lawfully refuse to cooperate if the conduct they have been pardoned for can also be prosecuted as a state crime.

CAN TRUMP PARDON HIMSELF?

There is not a definitive answer. No president has tried it before, so the courts have not weighed in.

“When people ask me if a president can pardon himself, my answer is always, ‘Well, he can try,’” said Brian Kalt, a constitutional law professor at Michigan State University. “The Constitution does not provide a clear answer on this.”

Many legal experts have said a self-pardon would be unconstitutional because it violates the principle that nobody should be the judge in his or her own case.

Trump could try to pardon himself preemptively to cover the possibility of prosecution for federal crimes after he leaves office. No pardon could protect him against prosecution for any crimes by a U.S. state.

For a court to rule on the pardon’s validity, a federal prosecutor would have to charge Trump with a crime and Trump would have to raise the pardon as a defense, Kalt said.

(Reporting by Jan Wolfe; Editing by Noeleen Walder and Leslie Adler)