WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. President Donald Trump hopes a recount of votes will help keep President-elect Joe Biden out of the White House, but as common as recounts may be, especially for state and local candidates, only three in the last two decades have changed the result and none for a presidential election.

Here’s how recounts work and the impact they have had:

WHAT IS A RECOUNT?

In a recount, authorities repeat the process of tallying up votes. They are a relatively common feature of U.S. elections, though rare in presidential contests.

“Recounts are routine. Run-of-the-mill,” said William & Mary Law School professor Rebecca Green. She said they usually show the first count to be fairly accurate, though small discrepancies, often caused by differing judgments about how to count ballots marked by hand and other issues, are not unusual.

States handle recounts differently, but the process mostly comes down to re-tallying the votes.

In Georgia, Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger said on Wednesday he had ordered a hand recount because of the closeness of the tally, although he believed ballots had been counted accurately and there was no sign of widespread fraud.

The latest Georgia tally put the Democrat Biden ahead of the Republican Trump by about 14,000 votes, 49.5% to 49.2%, a difference of 0.3% with nearly all votes counted. Raffensperger told CNN he wanted the hand count completed by Nov. 20.

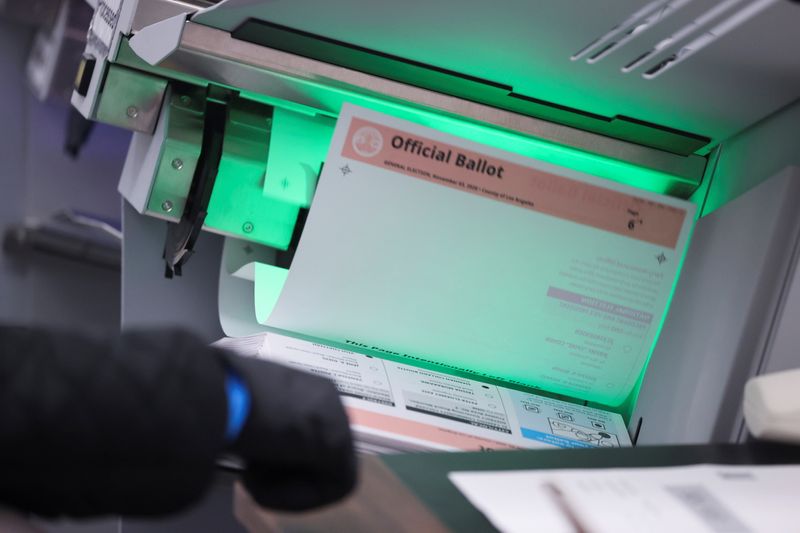

Voters in Georgia who showed up in person used a new touchscreen voting system that produced paper ballots that were fed into a scanner and counted. People who voted absentee used the same ballots that went through similar scanners.

When the machines could not determine which candidate a voter had selected, a bipartisan group of election officials reviewed the ballot to decide whether or how it should be counted.

Separately, Trump’s campaign has claimed, without much proof, that it has found evidence of ballots being cast in the names of people who were dead or had moved away, and that its volunteers had been prevented from scrutinizing ballot counting as closely as they wanted. Recounts will not address those issues, which have to be fought out in separate legal proceedings.

The process can take weeks, but some states also set a deadline for getting it done.

CAN TRUMP GET A RECOUNT?

Every state sets its own threshold for when to do a recount. Some require one whenever an election is especially close. In Pennsylvania, one of the states pivotal to Biden’s victory, a recount would be required if the margin between the winning candidate and the runner-up is less than 0.5% of the votes cast in the election. But Biden led Trump there by 0.8%.

Voters in an election district can separately petition their county to recount votes there and the law does not set a threshold for when one should occur.

Other states like Georgia and Wisconsin allow a losing candidate to force a recount but do not require one. Georgia allows candidates to seek a recount if the margin is less than 0.5%; Wisconsin allows one if it is less than 1%. In Wisconsin, Biden led by 0.7%.

Typically, candidates make those requests after a state has certified its final vote tally, which has yet to happen.

DOES IT MAKE A DIFFERENCE?

Recounts rarely upset the results of an election. When they have, it has been in cases in which only a few hundred votes separated the top two candidates.

A study last year by the non-partisan group Fair Vote concluded that states had conducted 31 statewide recounts between 2000 and 2019, and that the outcome changed in only three of them. That happened in a governor’s race in Washington state in 2004 and in a state auditor’s race in Vermont in 2006.

A recount also decided the result of a U.S. Senate race in Minnesota in 2008. Before the recount, the incumbent senator, Norm Coleman, was ahead by 215 votes; when it was over, his opponent, Al Franken, won by 225. But delayed by legal proceedings the contest took so long that the state’s U.S. Senate seat stayed empty for six months.

More often, in a recount the winner won by a tiny bit more. On average, they shifted the outcome by 0.024%, Fair Vote found – a vastly smaller margin than Trump would need to overtake Biden in any of the battleground states where he was losing by narrow margins.

Wisconsin recounted the presidential votes when Trump was elected in 2016. Green Party candidate Jill Stein, who won about 1% of the vote, sought the recount. The process added 131 votes to Trump’s tally.

The most famous presidential recount was in Florida in 2000, when George W. Bush was 1,784 votes ahead of Al Gore in a state that would determine which of them would be president. After a recount and litigation that went to the U.S. Supreme Court, Florida ultimately declared that Bush had won by 537 votes.

(Reporting by Brad Heath, editing by Ross Colvin and Howard Goller)