BANGKOK (Reuters) – Americans living abroad are asking Washington to send surplus coronavirus shots to overseas embassies so they can get a vaccine in countries where the pace of inoculations is slow and travelling home is difficult.

Many of the estimated 8 million Americans living abroad argue they should have the same right to a vaccine as U.S. citizens back home. The U.S. vaccination drive covers all of the population and surplus doses are earmarked for donation to India and other nations.

“Vaccines could be provided to U.S. citizens through U.S. embassies and consulates, in particular as many are now re-opening for U.S. citizen services,” said Marylouise Serrato, executive director of the advocacy group American Citizens Abroad.

The group last month wrote to the U.S. Congress and the State Department saying overseas Americans who file taxes and vote should have the same access to vaccines as U.S. residents.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki said this week the U.S. government is focused on the safety of Americans around the world but is not now prepared to provide vaccines.

“We have not historically provided private healthcare for Americans living overseas, so that remains our policy,” Psaki told reporters. “But I don’t have anything to predict in terms of what may be ahead.”

Many Americans overseas are travelling home if they can to be vaccinated or waiting for the inoculation campaign in their countries of residence. But those living in places where vaccine rollouts are slower or where travel is difficult say they feel stuck.

In Thailand, four U.S. citizens’ groups on May 6 wrote to U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken asking for the Southeast Asian country to be made a pilot project for global vaccination of Americans abroad.

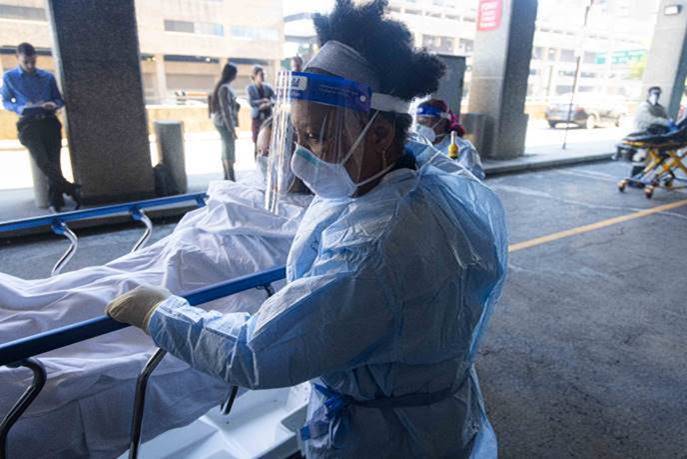

Thailand is in the midst of a deadly third wave of coronavirus, after a year of successfully containment, and its mass vaccination drive doesn’t begin until next month.

“JUST FORGOTTEN”

The U.S. State Department last month said it had already shipped doses to embassies and consulates in 220 locations worldwide to vaccinate its own diplomats and other employees.

The diplomatic distribution shows that the U.S. government has the capacity to do the same for citizens, said local chapters of the Democrats Abroad, Republicans Overseas, the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Women’s Club in Thailand.

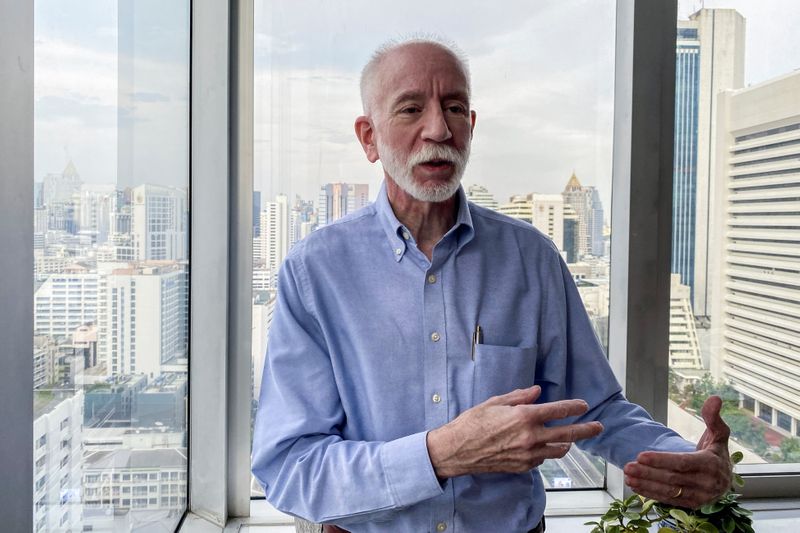

“We are tax-paying, voting U.S. citizens and we were promised that we would be eligible to be vaccinated by our government, and here we are being just forgotten,” said business owner Peter Fischbach, in Thailand for nearly 30 years.

He worries it may be weeks or months before he can get a shot in Thailand. His business obligations – plus Thailand’s strict two-week quarantine for people entering the country – make it unfeasible to return to the United States.

The U.S. Embassy in Bangkok declined to comment. There are no official figures on Americans living in Thailand, but Democrats Abroad estimates it as tens of thousands.

Financial tech worker Aaron Kruse, 32, was working in China along with his South African fiancee when the pandemic struck. The couple travelled to Cape Town, South Africa, where travel restrictions and then the South African variant of the virus have now derailed their plans.

“So now we’re very much stuck,” said Kruse, who is from Des Moines, Iowa.

South African’s American expatriate community has not made a formal request, as in Thailand, but even without such a request Kruse says he thinks U.S. embassies should provide vaccines to Americans in need.

But he also supports donating shots to needy countries and is keenly aware that should the U.S. bring in vaccines for its own citizens – this would be criticised.

“I do kind of see it as special treatment,” he said.

“But at the same time, if the United States is looking out for U.S. citizens, and we have a surplus of vaccines, then the next place to look for U.S. citizens must be where they live and reside overseas.”

(Additional reporting by Joe Bavier in Johannesburg. Writing by Kay Johnson; Editing by Alexandra Hudson)