(Reuters) -A top Federal Reserve official signaled on Wednesday he was ready to open talks on reducing some of the U.S. central bank’s emergency support for the economy, even if only to clarify the Fed’s plans as the economy roars ahead and prices rise.

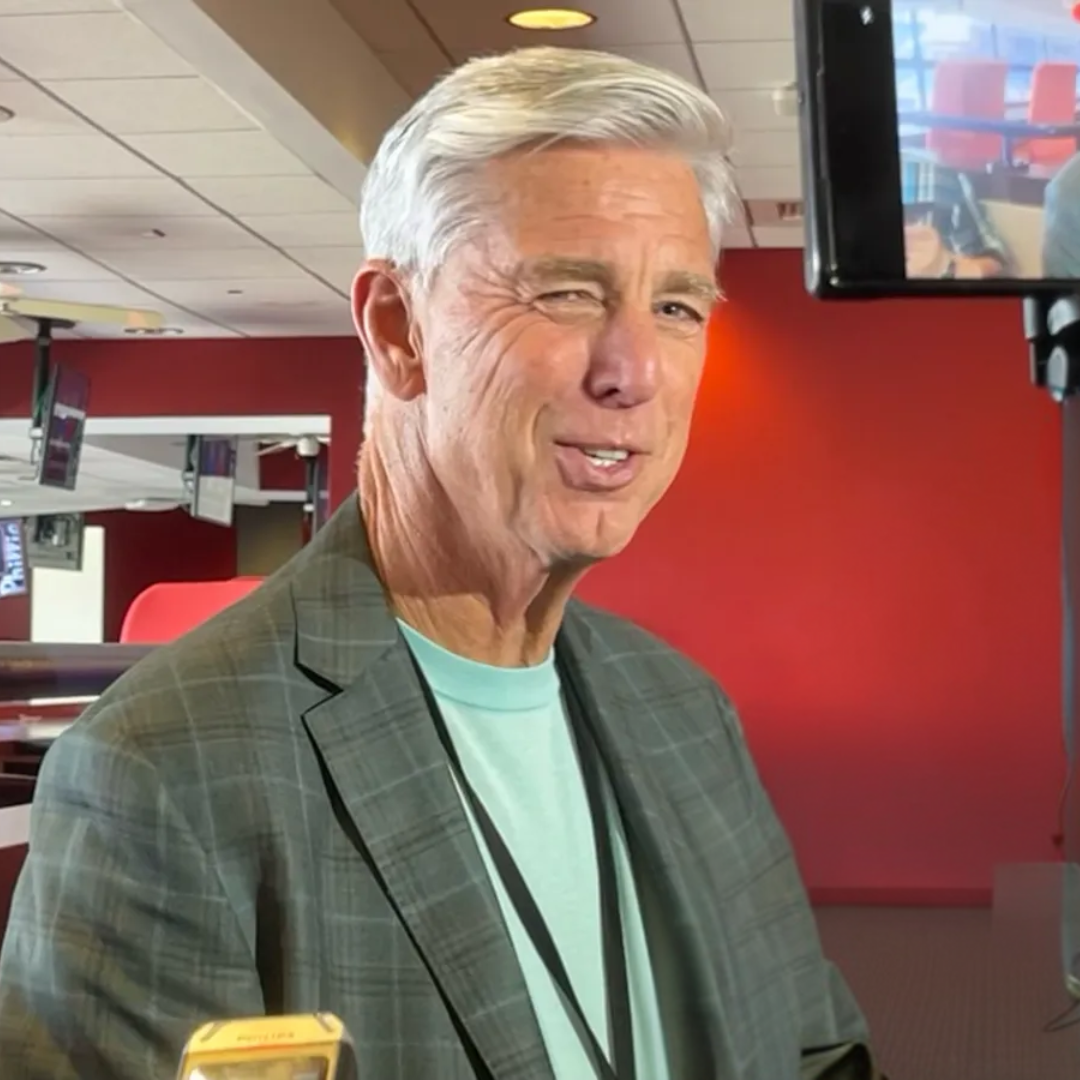

“I don’t want to overstate my concern,” the Fed’s vice chair for supervision, Randal Quarles, said at a Brookings Institution event. He noted he did not expect a round of 1970s-style breakout inflation, and that he was “fully committed” to a new Fed strategy that aims to keep monetary policy running full-throttle while jobs recover.

But he also laid out the case for why the “upside” risks of higher inflation may be mounting, and how the Fed may need to begin smoothing the way for a policy shift.

Quarles is the highest-ranking Fed official to begin making that case. Two Federal Reserve bank presidents have said they felt those discussions should start soon, if not right away, though Fed Chair Jerome Powell has maintained it is still too early.

Though “we need to remain patient” in any policy shift, Quarles said, “if my expectations about economic growth, employment and inflation over the coming months are borne out … and especially if they come in strong … it will become important for the (Federal Open Market Committee) to begin discussing our plans to adjust the pace of asset purchases at upcoming meetings.”

The Fed has been purchasing $120 billion in government securities since last spring. In December it said it would continue doing so until there had been “substantial further progress” toward the central bank’s maximum employment and 2% inflation goals.

The inflation hurdle will be cleared this year, and while employment is lagging, Quarles said the Fed may need to make clearer exactly what would qualify as “substantial” progress on jobs to guide people toward a possible policy shift.

“We may need additional public communications,” Quarles said. The Fed wants investors to anticipate its plans for the bond purchases to avoid any sharp adjustment in markets and rates when it begins. He said the current language represents “inherent communications challenges” because it does not rely on any particular measure of the job market.

An actual interest rate increase, Quarles said, “remains far in the future.”

Minutes of the Fed’s meeting in April and recent speeches by officials have showed the central bank edging toward a more overt discussion of when to change its bond program.

Recent data has been problematic, with inflation higher and employment growth slower than expected.

Quarles said he agreed that inflation pressures will likely ease over time, as will the forces keeping some people from jobs, whether childcare troubles or availability of unemployment benefits.

The risk comes if the Fed is wrong, and Quarles laid out why he feels coming inflation may prove more persistent. He worried that wages might accelerate faster than anticipated and get passed through to prices; federal spending might fuel stronger demand from households as people return to jobs while also flush with record savings; and that supply-chain bottlenecks might not ease before rising prices become entrenched.

Fed officials hope these circumstances will clear soon, with inflation easing and employment rebounding in ways that allow for a smooth, well-telegraphed transition to post-crisis policies.

University of Oregon economics professor Tim Duy, who appeared at the event with Quarles, said recent Fed comments put the central bank on a “very long runway towards tapering.”

The Fed’s chair, Powell, was likely to give clearer guidance by the central bank’s yearly conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in August, with bond purchases being reduced early next year or earlier if inflation turns out to be more intense or less transitory than currently expected.

(Reporting by Howard Schneider in Washington and Ann Saphir in Berkeley, Calif.Writing by Howard Schneider Editing by David Gregorio and Matthew Lewis)