GEOJE, South Korea (Reuters) – Clad in a black wet suit and pink face mask, Jin So-hee’s figure cleanly parts the green-blue water until she abruptly dives below the surface, her purple fins disappearing into the deep.

When she resurfaces a minute and a half later, her gloved hands grip six or seven sea cucumbers, their spiked backs glistening in the sun.

“This is the biggest one, what do we do?” she asks her partner, Woo Jung-min. “The boss is going to be mad. He told us to bring in the really big ones today.”

Climate change and environmental pollution have made finding enough sea life to harvest more difficult for Jin, Woo, and other South Korean haenyeo, or “sea women”.

For six years, Jin, 28, has dived the icy seas off the rocky shore of Geoje Island, gathering abalone, conches, seaweed and other marine life by hand to be sold in local markets.

Every year the waters are a little less icy – warming as much as 2.6 times more than the world average – changing the undersea habitat and casting doubt on the future of the haenyeo.

Jin and Woo, 35, are some of the youngest women following a centuries-old tradition of free-dive fishing without oxygen that has already faced massive upheaval in the face of advances in fishing practices and altered village life in the high-tech world of modern South Korea.

The vast majority of living haenyeo are now over the age of 70, and in neighbouring Busan, veteran divers told Reuters catches are now a fraction of what was harvested decades ago.

“I’ll continue unless I’m sick, and my wish is this seafood can live until then so that I can continue this work,” said 86-year-old Ko Bok-hwa, who has been a diver since she was 13.

Jin and Woo have tried to adapt, running a YouTube channel called “Yozum Haenyeo” (Modern Sea Women) to chronicle their lives and work, with their most popular video garnering more than 600,000 views.

But climate change may permanently dash their hopes of spending their lives working as free divers.

“I thought that as long as my body is healthy, I could have been the oldest haenyeo when I’m 90 or 100,” Jin told Reuters.

“Now that I think about it, my health is not the only concern. I’m worried this job will change drastically or even disappear because of climate change.”

INVASIVE SPECIES, VANISHING SEAWEED

Anecdotal evidence observed by haenyeo on the front lines of the changing environment is confirmed by South Korean scientists seeking to study and protect the country’s fisheries.

“Climate change caused the change of habitat of sea life and the influx of non-native species,” said Ko Jun-cheol, a researcher at the National Institute of Fisheries Science.

Between 1968 and 2017, the sea surface temperature around Korea rose 1.2 Celsius (2.2 Fahrenheit) degrees, compared to a world average of 0.48 Celsius degrees, he said.

Warmer waters have brought new, subtropical species that have displaced the haenyeo’s traditional catch, and changed the sea floor habitat by introducing more stony coral and killing off seaweed forests. Large beds of seaweed have disappeared, replaced by rock-like coralline algae and resulting in the decrease of marine resources.

As recently as the 1990s, scientists would see one or two subtropical species around the islands of Korea’s south coast, but a study covering the years 2012-2020 found 85 kinds of subtropical species, accounting for more than half of all sea life in some places, Ko said.

Since 2011 the government has also been working to reverse the ocean desertification caused by climate change.

The Marine Forest Creation Project involves planting new seaweed, which helps absorb carbon dioxide from the water, and removing the invasive sea urchins that eat the marine plant, said Jeon Byung-hee, an official with the Korea Fisheries Resources Agency’s Ecological Restoration Division.

“If seaweeds disappear, it takes away a source of food for animals, spawning grounds, and habitats,” he said.

‘REALLY SERIOUS’

With less seaweed, which the haenyeo also harvest as food, the women increasingly have to dive deeper, Jin said.

That’s more physically challenging, and the women say they have to deal with more pollution as well, further complicating their already dangerous jobs.

“I’m finding more golf balls than sea cucumbers now,” Jin said.

The haenyeo say the changes are becoming more pronounced every year, which is of particular concern for the dwindling number of young divers hoping to keep the tradition alive – and make enough to keep food on their own tables.

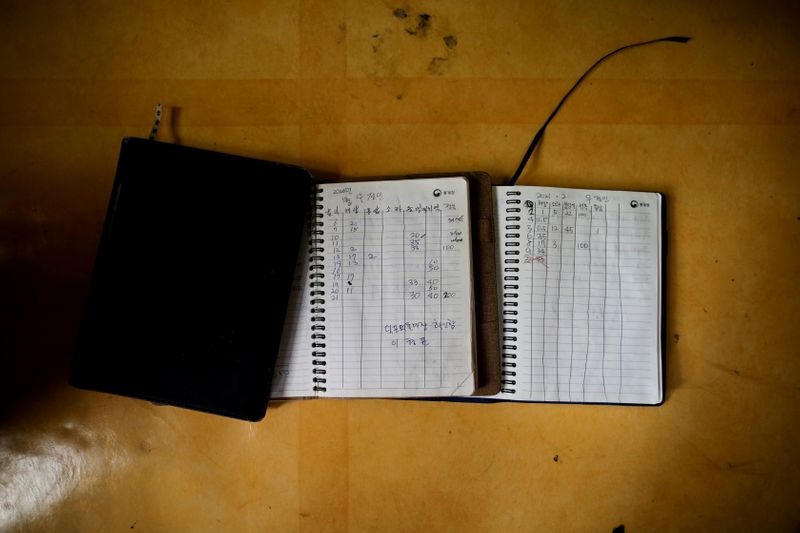

“The problems seem very real to us,” Woo said after evaluating her diminished catches and tallying up her totals for a recent pay day.

“Today, I’m thinking once again, ‘This is really serious.'”

(Reporting by Hongji Kim and Hyun Young Yi in Geoje, and Josh Smith in Seoul; Editing by Tom Hogue)