MUNICH (Reuters) – German scientists plan to clone and then breed this year genetically modified pigs to serve as heart donors for humans, based on a simpler version of a U.S.-engineered animal used last month in the world’s first pig-to-human transplant.

Eckhard Wolf, a scientist at Ludwig-Maximilians University (LMU) in Munich, said his team aimed to have the new species, modified from the Auckland Island breed, ready for transplant trials by 2025.

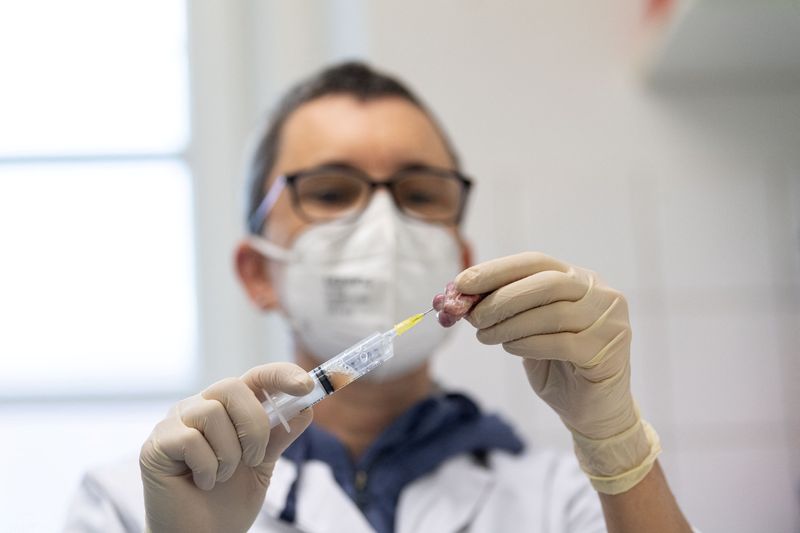

In the first surgery of its kind, a team at the University of Maryland Medicine last month transplanted a heart from a pig with ten modifications into a terminally ill man. His doctors say he is responding well though risks of infection, organ rejection or high blood pressure remain.

“Our concept is to proceed with a simpler model, namely with five genetic modifications,” said Wolf, whose work has triggered a heated debate in a country with one of Europe’s lowest organ donation rates and a strong animal rights movement.

Wolf, who has been researching animal-to human-transplants – known as xenotransplants – for 20 years, said his team would use still inefficient cloning technology to generate only “the founder animals”, from which future genetically identical generations would be bred.

The first such generation should be born this year, and their hearts would be tested in baboons before the team sought approval for a human clinical trial in two or three years’ time, Wolf said.

Transplants are used for people diagnosed with organ failure who have no other treatment options, a waiting list that numbered around 8,500 people in Germany at the end of 2021, according to data from the country’s Organ Transplantation Foundation.

Wolf’s supporters say animal donors could help shorten that list, but opponents say the technology rides roughshod over the rights of animals, effectively degrading pigs to the status of organ factories while the monkeys used in transplant experiments die in agony.

In February 2019, a petition by German pressure group Doctors Against Animal Experiments demanding a ban on xenotransplantation research collected over 57,000 signatures.

Kristina Berchtold, a spokesperson for the Munich branch of Germany’s Animal Welfare Association, called the practice “ethically very questionable.”

“Animals should not serve as spare parts for humans,” she said. “… A pet, a so-called farm animal, a clone or a naturally born animal all have the same needs, fears and also rights.”

(Reporting by Riham Alkousaa, Ayhan Uyanik and Marcus Nagle)