Following Trump’s win on Tuesday, you may have seen a trend on your social media feeds: many women are talking about getting IUDs (intrauterine devices) in the next couple months before the president-elect’s January inauguration. And it’s not just online chatter: representatives from Planned Parenthood have reported an increase in calls made to schedule IUD appointments in the last week.

Women are worried about losing access to contraception, both preventative and procedural, under a Trump presidency. There is ample reason to be worried: Trump has said in his 100 day plan that he plans to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which currently requires insurers to cover FDA-approved methods of birth control, from pills to IUDS.

He’s also been vocal about appointing anti-abortion Supreme Court justices in an effort to repeal Roe vs. Wade, the landmark case that legalized abortion. He told CBS’ Leslie Stahlon “60 Minutes” that if it were overturned, the decision would go to the states, in which case, some women opting for an abortion “would have to go to another state.”

While we can only guess what Trump might accomplish during his term, it can’t hurt to prepare for the worst case scenario. And getting an IUD, which lasts for three to 10 years depending on which kind you opt for and is currently the most effective birth control method — at more than 99% effectiveness, according to Planned Parenthood— could safeguard you against unwanted pregnancy through a Trump presidency and beyond.

What do you need to know about getting one? We asked Dr. Laura MacIsaac, MD, MPH and Director of Family Planning for the Mount Sinai Health Systems, to give us a primer.

Mount Sinai provides roughly 1,000 IUDs a year, and according to MacIsaac they’re “the most effective [birth control] with the least amount of side effects.”

What is an IUD and how does it work?

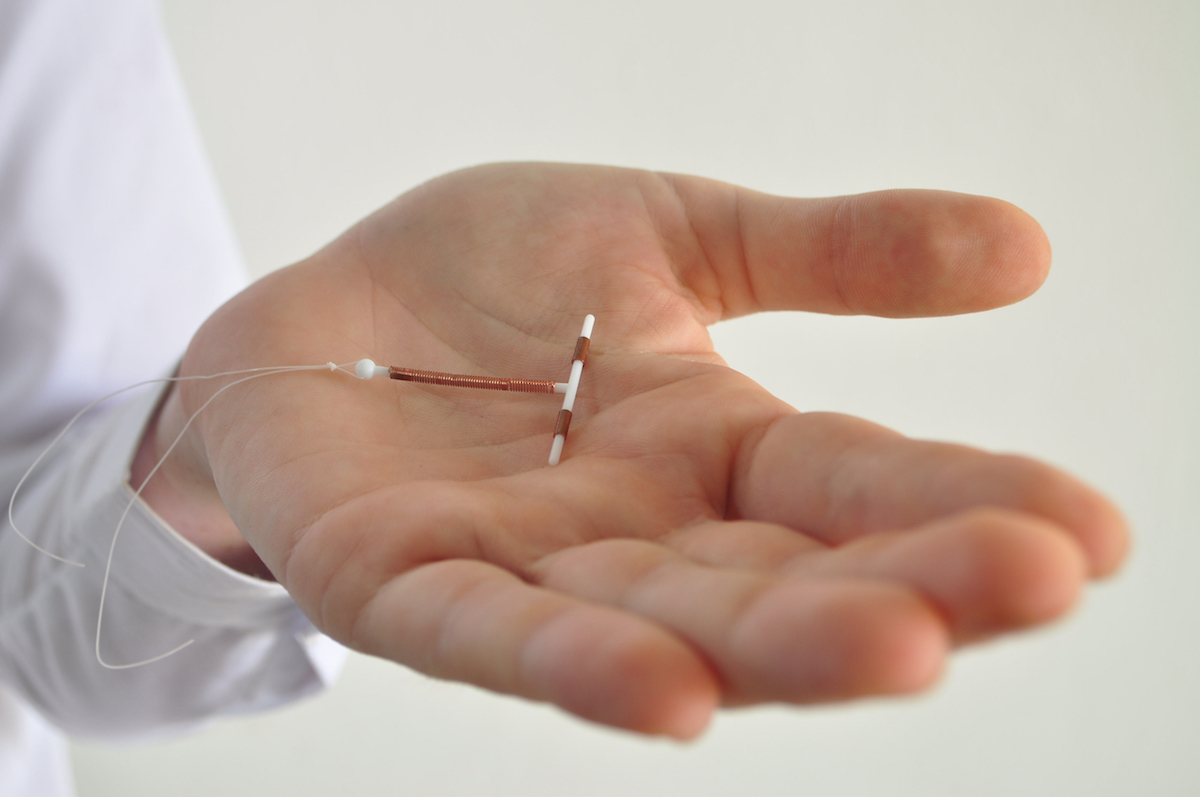

An IUD is a small, often T-shaped contraceptive device that’s inserted into the uterus to prevent pregnancy. It uses either hormones or copper to thicken cervical mucus to block sperm from fertilizing the egg.

Insertion

The procedure of getting an IUD inserted, while brief, can be painful for women who haven’t had children yet and therefore haven’t had their cervix dilated. In that case, MacIsaac normally recommends a high dose of Motrin taken with food before the procedure.

There are two main categories of IUDS: hormonal and copper.

“The bleeding pattern is the biggest difference, and duration of action is second,” says MacIsaac of the two options.

The four hormonal products, which MacIsaac describes as “sisters that are much more the same than different,” all use Levonorgestrel, a Progestin hormone, which goes into the uterus and is not systemic—meaning, it’s undetectable in the blood stream. “When people hear ‘hormonal IUD’ they think hormonal birth control and they think the pill, and that it has all the same risks as the pill, which is completely wrong thinking,” MacIsaac explains.

These IUDs use slightly different doses of the hormone, which affect how long they last and how much they suppress your period. Mirena and Kyleena are currently approved for five years and the Liletta and Skyla, for three. With Liletta and Mirena, one in five women see their period stop after a year, compared to 6% with the Skyla and 12% with the Kyleena. The patient experience is roughly the same, says MacIsaac.

The copper option, ParaGard, lasts for 10 years and is completely hormone-free. Women who already have heavy periods and cramping should know its major side effect is that it makes periods even heavier and cramps worse.

“If it’s a purely economic argument, there’s no question that the copper IUD wins, because it has the longest duration of action and it’s the less expensive,” says MacIsaac.

Getting it removed

Once you remove your IUD, you regain fertility immediately. Any physician, including a nurse practitioner, can remove it, so if you were to lose your health insurance under Trump, as long as you can get to a doctor’s office and pay the appointment fee, you can take care of it.

Is there anyone who shouldn’t get one?

“There are only a few contraindications,” says MacIsaac. For some women who have an irregular shape to their uterus, called a uterine anomaly, an IUD often doesn’t stay in well, she explains. A patient with breast cancer shouldn’t use a hormonal IUD, because lab studies have shown the Levonorgestrel could stimulate tumor growth in cancer cells.