CINCINNATI/TABLERS STATION, W.V. (Reuters) – Procter & Gamble Co may be best known for laundry detergent and toothpaste, but its secret sauce is arguably figuring out how to do things like get two red bottles of Olay skin lotion into blister packs as cheaply and accurately as possible.

That task is currently done by hand at its factories.

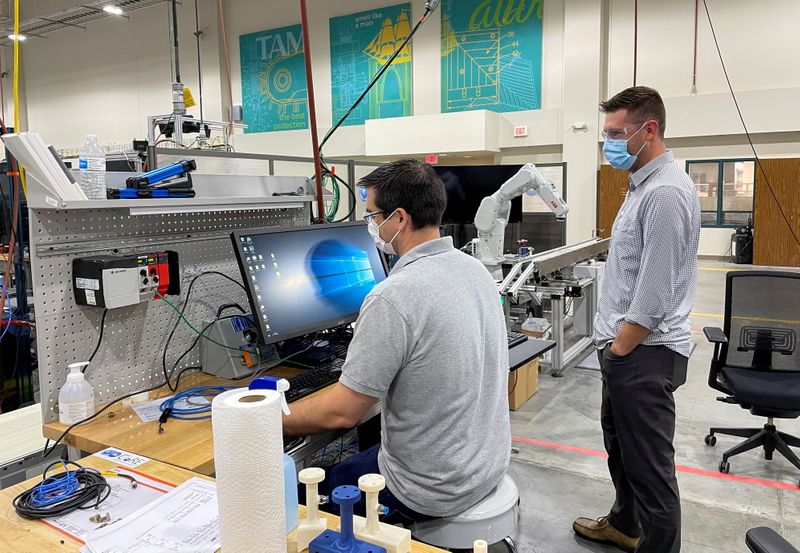

But at one of the conglomerate’s secretive robotics labs on the outskirts of Cincinnati, researchers have programmed a robot to do the job.

It’s a surprisingly tricky maneuver for a machine. The robot arm plucks two bottles at a time from a box and lays them into the dimples with the labels facing forward so they’re visible when the package is sealed.

“That’s the key – getting the labels exactly oriented,” said Mark Lewandowski, director of robotics innovation at P&G’s global engineering center, pointing to the test line he’s set up inside the facility. “We’ll be rolling this out in the next month or two” to P&G’s factories, he said.

Many companies make consumer goods. Yet it’s ones who can make them the most eye-catching for consumers, and do it as cheaply as possible, that do best.

In that regard, P&G is a model and its use of high-speed automation and robots is a key to its success. P&G is the world’s largest consumer-goods maker and dominates many of its businesses. For example, analysts estimate its Bounty brand accounts for 40% of all paper towels sold in the United States. Investors appreciate its steady profits and dividends. The company has raised its dividend 65 years in a row.

To be sure, P&G is mainly known as a branding expert, not a designer of factory machines. But developing key pieces of its own automation has helped it compete in businesses where shaving fractions of a penny off the cost of making each Pampers diaper and Gillette razor blade is essential.

And the pressure to cut costs is stronger than ever. Like other manufacturers, P&G is pushing through price increases to offset a surge in raw material and shipping costs.

“In commodity businesses like P&G’s, price is everything,” said David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who studies the impact of automation. “For that kind of business, you need scale and efficiency,” and that means staying on the cutting edge of production technology.

GETTING IT INTO A BOX

Lewandowski’s lab, tucked in a nondescript brick building surrounded by suburban shopping plazas, works on robots that could end up in a factory at any one of P&G’s six main business units. The robot that handles Olay bottles, for example, was developed as part of a larger challenge of creating machines and grippers that can handle bottles and tubes of many shapes and sizes and get them into increasingly complex packaging.

“Everyone talks about the Amazon challenge – the gripping and picking,” said Lewandowski, referring to the online retailing giant. But for P&G, it isn’t enough to just get a bottle into a box.

Consumer products designers are constantly dreaming up new shapes and sizes of containers, sometimes adding features like pour spouts or clamp-down lids, to help products stand out on grocery shelves. That can mean costly adjustments to machinery every time a line switches to a new product.

The COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the development of some new automated systems. At many P&G factories, Lewandowski noted, clusters of hourly workers come together – often shoulder to shoulder – to assemble special assortments or the cardboard displays that highlight products at the end of grocery aisles.

“People are still the ultimate machine” for that job, he said. But over the past year, he’s found ways to automate more of it – in part to aid social distancing. This push to automate this hand work is likely to continue beyond the pandemic, he noted, because P&G’s factories are struggling to find workers willing to do these jobs in tight labor markets.

NOT FOR EVERY JOB

In addition to Lewandowski’s lab, P&G operates a network of separate research centers that focus on automation problems unique to each business.

A few miles away, for instance, is a research center devoted to the fabric and homecare business. This lab, with a huge vintage advertising photo of a woman hanging up laundry on a clothesline in the entry, has existed for three decades. But only in the last five years has it created a section that focuses on pure robotics rather than more generic automated machinery.

Roger Williams, the lab’s technical director, estimates that only 20% of the automation in P&G’s factories involves true robots, which are slower than “fixed automation” such as machines that squirt detergent into a bottle or fasten caps. But that is up from 10% a decade ago.

Williams said he always has a “hit list” of 15 projects on the floor of his lab, each aimed at determining the feasibility of using robots for a given task. He was recently asked, for instance, to determine if a robot could stuff bags of powdered detergent into boxes – a relatively new type of packaging for their Tide brand.

“That one didn’t move forward,” he said. While it was possible, the cost to install and program the robots didn’t justify the investment for a relatively small-volume item.

FLEXIBILITY AND AGILITY

Another project, still underway, is aimed at finding a way to move a new bottle cap type onto the detergent-bottle filling assembly line. That is typically done with a “unscrambler,” a mechanism that shakes and turns piles of caps until they are oriented to feed into the filling machine. The new caps can’t go through that because they include a delicate device that could be damaged.

“We’re working on a robot that will pick up 40 caps at a time and index them into the final system,” he said.

At one of the company’s newest plants, in Tablers Station, West Virginia, robots dot the production floor. On a recent day, fast-moving arms were plucking pink Pantene hair conditioner tubes and placing them onto a line to be filled.

“We’re always looking for places where we need flexibility and agility,” said Jim Utter, a project manager at the plant. One of the big opportunities he sees is adding more mobile robots, which could be used to move bundles of parts between different parts of the plant. The newest models can find their way around unexpected obstacles, rather than relying on fixed tracks.

“That’s essential in place like this, where everything is always moving,” he said.

(Reporting by Timothy Aeppel; Editing by Dan Burns and Nick Zieminski)