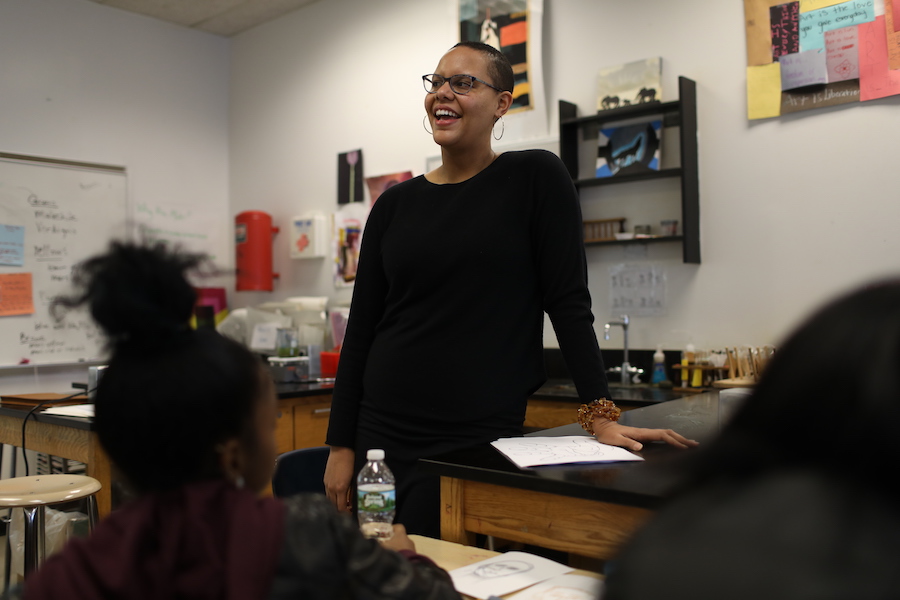

Muffled piano chords filter into the hallway as a few straggling students head for their class in “Tricksters, Fools and Scoundrels: Comedy as a Window on the World.”

So begins another day at Manhattan’s Harvest Collegiate High School, where classes with offbeat course titles meet on the upper floors of a Party City store, teachers are called by their first names and students who cut class face a panel of their peers. Harvest is different from most public schools, and it’s by design, courtesy of founder and principal Kate Burch and 38 teachers.Their freedom to innovate is made possible by a teachers’ union grantthat allows some Department of Education rules to be broken and bymembership in a state consortium of schools that reject standardizedtesting. In June, the four-year-old school, on West 14th Street, celebrated itsfirst graduating class, not necessarily with balloons and noisemakersfrom downstairs, but with a 96 percent graduation rate — well above thecitywide average of 70.5 percent. Now local principals and academicsfrom Japan and Iceland are coming to observe to see what the buzz isabout. Lastyear,2,461appliedfor120freshmanspots.Almost30percentarespecialeducationstudentsintegrated into regular classes with anIndividualized Education Plan (IEP).

“People ask us our theme or what we’re preparing students for,” saidBurch, who has degrees from Harvard and Columbia and has worked inIndia, France, and Ghana. “We say our theme is you, the student. Weteach them to think deeply and well.” The course catalog reads like a college electives list: EngenderingGender, War and Imagery, Track and Field Through an Algebraic Lens,Atoms to Humans. Students take four years of core subjects.

“It’s just that their science class may be Designing a Computer Game, or their history class may be in world religions or economics,” Burch said.

To graduate, students must publicly present a capstone project to a panel. The only Regents Exam taken is English.

Students’ families hail from 34 countries and speak 25 languages.

“Our school is New York in a nutshell,” said Liana Donahue, an IEPEnglish teacher, studio art teacher and director of student recruitment.“Commitment to diversity is one of Harvest’s core values, and I thinkit’s what makes Harvest special.” One universal language, however, is music. All ninth- and 10th-graderslearn an instrument. “If you come in at 8:15 in the morning, you’ll hearpiano playing,” Donahue said.

Students started K-pop, debate, anime, and Black Lives Matter clubs, sheadded.

They yearn to solve real-world problems, said teacher John McCrann. “Ihad a geometry student say, ‘There’s so much pain and suffering in theworld. How can I be thinking about a rectangular prism?’ Unbeknownst toher, the next day we were going to be using the volume and surface area of a rectangular prism to think about how to provide aid in a disaster zone.” Discipline is handled differently: “You’re not being sent to theprincipal’s office like tsk, tsk, tsk, with finger waving,” said Burch.A panel of students and a few teachers problem-solve and determineconsequences for offenses like tardiness and incomplete homework. Omar Camps-Kamrin, 18, of Inwood, an alumnus now at Swarthmore College, mediated with the panel.

“At first it was kind of intimidating to be with a teacher and studentto work things out,” he said. “But both of them were like, ‘I recognizeI did this,’ ‘I should work on this.’”

Reflecting on his time at Harvest, Camps-Kamrin said, “When I came in, Iwas a shy kid with long hair who wasn’t comfortable putting myself outthere. Now I have shorter hair, but I feel motivated and more equippedto handle the world.” His classmate Karen Smith, 18, from East New York, Brooklyn, who attends SUNY Oneonta, agrees that Harvest prepared her well.

“The Collegiate part lived up to its name,” she said. “Writing a 10-pagepaper is almost like writing five now. It comes effortlessly.”

Harvest Collegiate shines with unconventional approach

Bess Adler