HONG KONG (Reuters) – Hong Kong’s pro-democracy opposition lawmakers said on Wednesday they would resign in protest against the dismissal of four of their colleagues from the city assembly after Beijing gave local authorities new powers to further curb dissent.

The Chinese parliament earlier adopted a resolution allowing the city’s executive to expel lawmakers deemed to be advocating Hong Kong independence, colluding with foreign forces or threatening national security, without having to go through the courts.

Shortly afterwards, the local government announced the disqualification of four assembly members who had previously been barred from running for re-election as authorities deemed their pledge of allegiance to Hong Kong was not sincere.

The moves will raise further concern in the West about the level of Hong Kong’s autonomy, promised under a “one country, two systems” formula when Britain ended its colonial rule and handed Hong Kong back to China in 1997.

Britain’s foreign minister Dominic Raab said the expulsion of the four lawmakers constituted an assault on Hong Kong’s freedoms as set out in the UK-China Joint Declaration.

“This campaign to harass, stifle and disqualify democratic opposition tarnishes China’s international reputation and undermines Hong Kong’s long-term stability,” Raab said in a statement.

The U.S. national security adviser, Robert O’Brien, said the move showed the Chinese Communist Party had “flagrantly violated its international commitments” and the United States would “continue to identify and sanction those responsible for extinguishing Hong Kong’s freedom.”

On Monday, Washington imposed sanctions on four more officials in Hong Kong’s governing and security establishment over their alleged role in crushing dissent.

In August, it put sanctions on Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam, the territory’s current and former police chiefs, and other top officials.

At a news conference in Hong Kong which started with all opposition lawmakers holding hands, Democratic Party chairman Wuu Chi-Wai said: “We can no longer tell the world that we still have ‘one country, two systems, this declares its official death.”

“CORE VALUES”

Opposition members of the city assembly, all part of the moderate old guard of democrats, say they have tried to make a stand against what many people in Hong Kong see as Beijing’s whittling away of freedoms and institutional checks and balances, despite a promise of a high degree of autonomy.

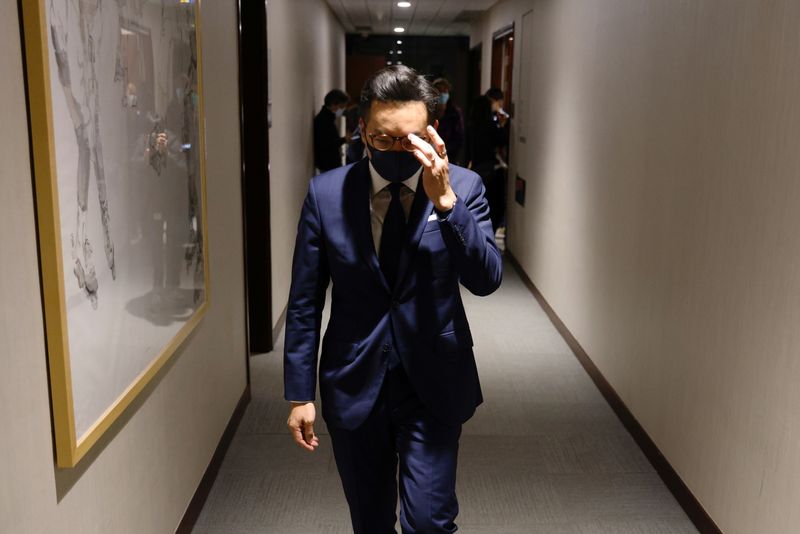

“My mission as a legislator to fight for democracy and freedom cannot continue but I would certainly go along if Hong Kong people continue to fight for the core values of Hong Kong,” one of the disqualified lawmakers, Kwok Ka-Ki, told reporters.

China denies curbing rights and freedoms in the global financial hub, but authorities in Hong Kong and Beijing have moved swiftly to stifle dissent after anti-government protests flared in June last year and plunged the city into crisis.

The city government said in a statement the four legislators – Kwok, Alvin Yeung, Dennis Kwok and Kenneth Leung – were expelled from the assembly for endangering national security.

Carrie Lam later told a briefing she welcomed diverse opinion in the 70-seat legislature but the law had to be applied.

“We could not allow members of a Legislative Council who have been judged in accordance with the law that they could not fulfil the requirement and the prerequisite for serving on the Legislative Council to continue to operate,” she said.

Shortly after the disqualifications, China’s representative office in the city said Hong Kong had to be ruled by loyalists.

“The political rule that Hong Kong must be governed by patriots shall be firmly guarded,” the Liaison Office said.

DAMNED EITHER WAY

Analysts say mass resignations remove democracy activists’ access to a forum where they could question policymakers and make them more accountable to public opinion.

But staying could have been perceived by their supporters as legitimising Beijing’s move and led to discord.

“Both staying and leaving have their own difficulties,” said Ma Ngok, associate professor of government and public administration at Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Concern about Hong Kong’s promised high autonomy, which underpins its role as an international financial centre, has grown since June 30, when Beijing imposed national security legislation on the city.

The law punishes anything China considers subversion, secessionism, terrorism or collusion with foreign forces with up to life in prison.

Since then, authorities have removed some pro-democracy books from libraries, banned certain songs and other activities in schools, declared some slogans illegal and raided the newsroom of an anti-government tabloid.

This month, eight other opposition politicians were arrested in connection with a legislative meeting in May that descended into chaos.

Government supporters say the authorities are trying to restore stability in China’s freest city after a year of unrest.

(Additional reporting by Marius Zaharia, Donny Kwok, Joyce Zhou and Farah Master in Hong Kong; additional reporting by David Brunnstrom in Washington , Writing by Marius Zaharia, Editing by Robert Birsel, Angus MacSwan and Gareth Jones)