HONG KONG (Reuters) – Fearing their work may violate a national security law recently imposed by Beijing, some Hong Kong artists are turning to self-censorship while others are moving their creations abroad or are planning to leave the city themselves.

The law, enacted in June, punishes subversion, secessionism, terrorism or collusion with foreign forces with up to life in prison, raising fears it effectively crushes wide-ranging freedoms promised to the city for 50 years after its 1997 handover by former colonial master Britain.

The city government, which has ambitions for Hong Kong to rival Paris or New York on the arts and culture scene, says the law does not curb rights and freedoms but will restore order and preserve prosperity after a year of anti-government unrest.

Nevertheless, the impact of the law is showing up in different spheres of daily life: pro-democracy books have been taken off shelves in libraries, shops have removed protest-themed decorations, a protest anthem and other activities have been banned in schools.

Nearly 2,000 Hong Kong and international artists and cultural workers said in a statement the security law created “a climate of fear and self-censorship”.

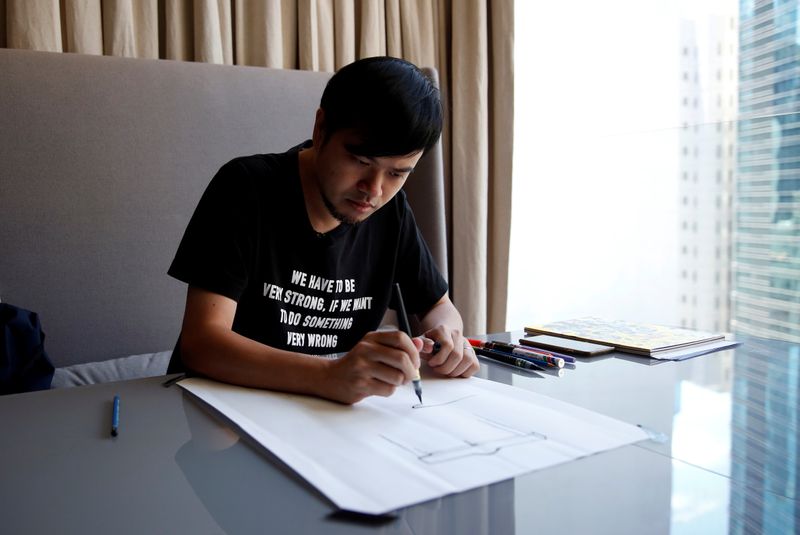

Illustrator Lau Kwong Shing’s fine-line drawings will no longer touch on themes of the pro-democracy movement as he shifts his focus to relocating.

“I’ve chosen to leave. For the moment, I want to protect myself,” Lau said, adding he would resume drawing once out of Hong Kong. He did not say where he hoped to move.

Him Lo, another artist now avoiding politics, moved his works, including a yellow banner that reads “Recapture Hong Kong” into storage at a European museum for safe-keeping. He declined to say where.

“I’m worried art works will be seized,” he said.

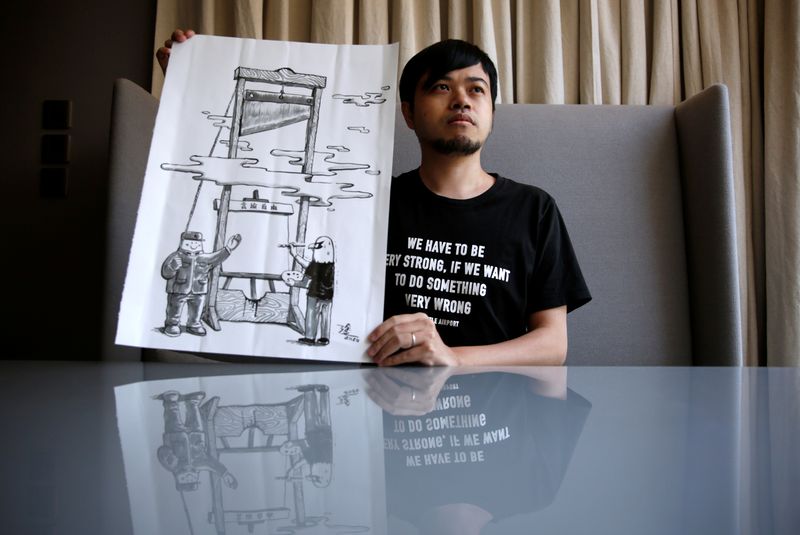

An artist using the pen name Childe Abaddon published “Voices”, a collection of protest works, including cartoons, by mostly anonymous contributors just months before the new security law was imposed.

He’s not planning a second edition.

“It was lucky that we put out the book before,” he said. “The book sold well, but we won’t consider publishing any more.”

The artist did not want to be identified by his real name because of the sensitivity of the topic.

‘MAKE AN IMPACT’

The city government said the new law upholds the “principles of respecting and protecting human rights”.

“When exercising these rights, art practitioners need not worry as long as they do not contravene the offences as defined under the law,” the government said in a statement.

“The legitimate rights of Hong Kong citizens to exercise their freedom of speech, such as making general remarks criticising government policies or officials, should not be compromised.”

The government’s Hong Kong Arts Development Council said artists getting support should ensure their works “conform with all legislations, rules, regulations and statutory requirements”.

A political illustrator who goes by the pen name Ah To, whose cartoon column was dropped by the Ming Pao Weekly newspaper last month, is defiant.

“You have to decide and judge what your values are, you can possibly be arrested at any time, or regret that you have not done enough to try to make an impact on society,” said Ah To, who declined to be identified by his real name because of the sensitivity of the issue.

“I’ve decided at this stage to continue and persist.”

Ming Pao, which had featured Ah To drawings on topics censored on the mainland such as China’s 1989 crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in and around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, said the decision to stop running his work was part of a revamp and not related to the new law.

(Reporting by Pak Yiu; Editing by Marius Zaharia and Robert Birsel)