(Reuters) – At the Custard Stand restaurant in Webster Springs, West Virginia, Angie Cowger worries Democrats’ goal of raising the hourly minimum wage to $15 would be the death knell for her business.

Roughly half her employees make about $9 an hour. Cowger can’t imagine raising prices on hot dogs and ice cream by enough to cover $15, so she would expect to lay off workers, perhaps having customers place orders on a screen rather than with a cashier.

“I don’t know our customer base would support that,” Cowger said of her rural town of about 700 people. “We’re in a town that has only one red light in the whole county.”

While an effort to raise the national minimum wage from its current $7.25 level without Republican votes was blocked in the Senate this month, congressional Democrats have signaled they plan to try again.

The stakes are perhaps nowhere better illustrated than in West Virginia. Its 16% poverty rate is among the nation’s highest and its low wages – half its workers earn less than $16.31 an hour – mean it could see some of the biggest risks and rewards of such a move.

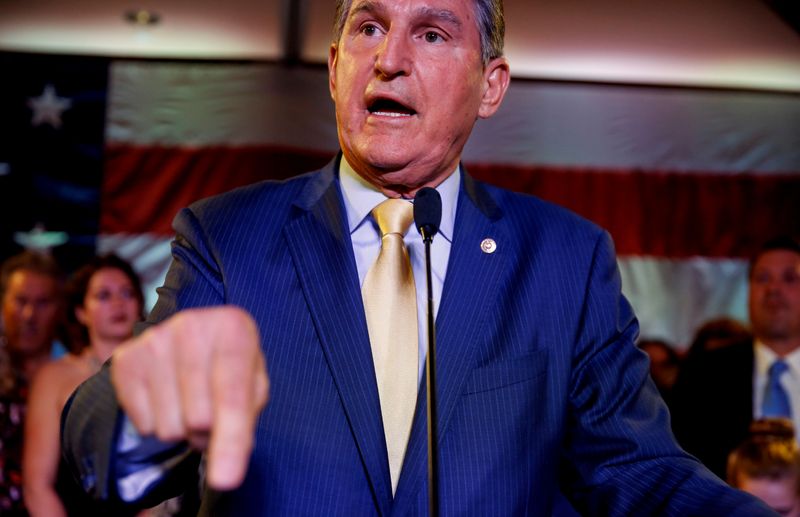

West Virginia is also home to Senator Joe Manchin, a moderate Democrat who opposes the $15 target and is emerging as a key force in the narrowly divided chamber.

Manchin, whose support would be crucial to the success of any legislation on the issue, says he would back an $11 minimum wage, still a more than 50% increase from where it has stood since 2009.

Five Senate Republicans – including West Virginia’s other senator, Shelley Moore Capito – have proposed an increase to $10, suggesting compromise of some kind is possible.

In Republican-dominated states, where wages are generally lower than in Democratic-leaning states that are home to America’s biggest cities, the biggest concern is retaining jobs, not raising wages.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) said in February that raising the minimum wage to $15 by 2025 as proposed by Democratic President Joe Biden would reduce the number of jobs nationwide by 1.4 million, and possibly by as much as 2.7 million, as businesses struggle with higher costs.

That hit would come after the pandemic sent the jobless rate well above 15% in West Virginia, higher than the national average. The state’s current 6.5% unemployment rate is just above the national level.

SPLIT ON JOBS

Some experts said job losses could be sharper in rural areas because it will be harder for businesses in small-town America to raise prices enough to offset dramatic increases in pay.

“It’s not surprising that the elected officials in low-wage states are more reticent to support higher minimum wages,” said Michael Strain, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute.

Nine of the 10 states with the lowest median hourly wage – a group that includes West Virginia – picked Republican Donald Trump in the 2020 election. Biden took nine of the ten states with the highest typical hourly wage. (For a graphic on hourly wages across U.S. states, click here: https://tmsnrt.rs/3bP1qcT)

Some experts say there is no evidence linking a higher minimum wage to job cuts, however.

“We do not detect any negative employment effects in our sample, and so I would not expect any in WV,” said Michael Reich, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley.

Labor activists are putting pressure on Manchin and Capito to go big on a minimum wage hike in West Virginia, where Trump beat Biden by nearly 40 percentage points and where well-paying coal jobs – long the state’s trademark industry – have been on the decline for decades.

They point out that the CBO study also projected that bringing the minimum wage to $15 by 2025 would boost the incomes of 17 million people nationally and pull 900,000 people out of poverty.

Last month, the activists hired vans to circle Capito and Manchin’s offices in Charleston, the state capital, with mobile billboards demanding $15 an hour. The Poor People’s Campaign also organized a rally outside of Manchin’s office promoting the rise.

Pam Garrison, a 62-year-old retiree who has held minimum-wage jobs for her entire working life, mostly as a cashier, said low wages were part of what held the economy back.

“If you give us the money, we’ll get this economy going,” she said from Fayette County, a coal mining area. “We spend our money. We will fix our falling-down houses up.”

(Reporting by Jason Lange and Makini Brice in Washington; Editing by Scott Malone and Sonya Hepinstall)