The festival runs Labor Day weekend in the North End.

The festival runs Labor Day weekend in the North End.

Credit: Getty Images

Anthony is the patron saint of finding lost things. Bostonians know, for four days in August he’s also the unofficial patron saint of losing a bunch of them – belt buckles, girlish figures, the ability to hide behind thin objects or wear your favorite shirt. For the four days of the Feast of St. Anthony in the North End, there are the other 360 or so days of planning. Feeding the North End “the feast of feasts” takes endless work.

To see the statue of St. Anthony parade through the streets, it’d be easy to assume the event is funded by the crowd-donated streamers of money, called calendars, strewn around the saint. And that’s how it used to be. But as the North End Italians spread throughout the country, that’s no longer an option.

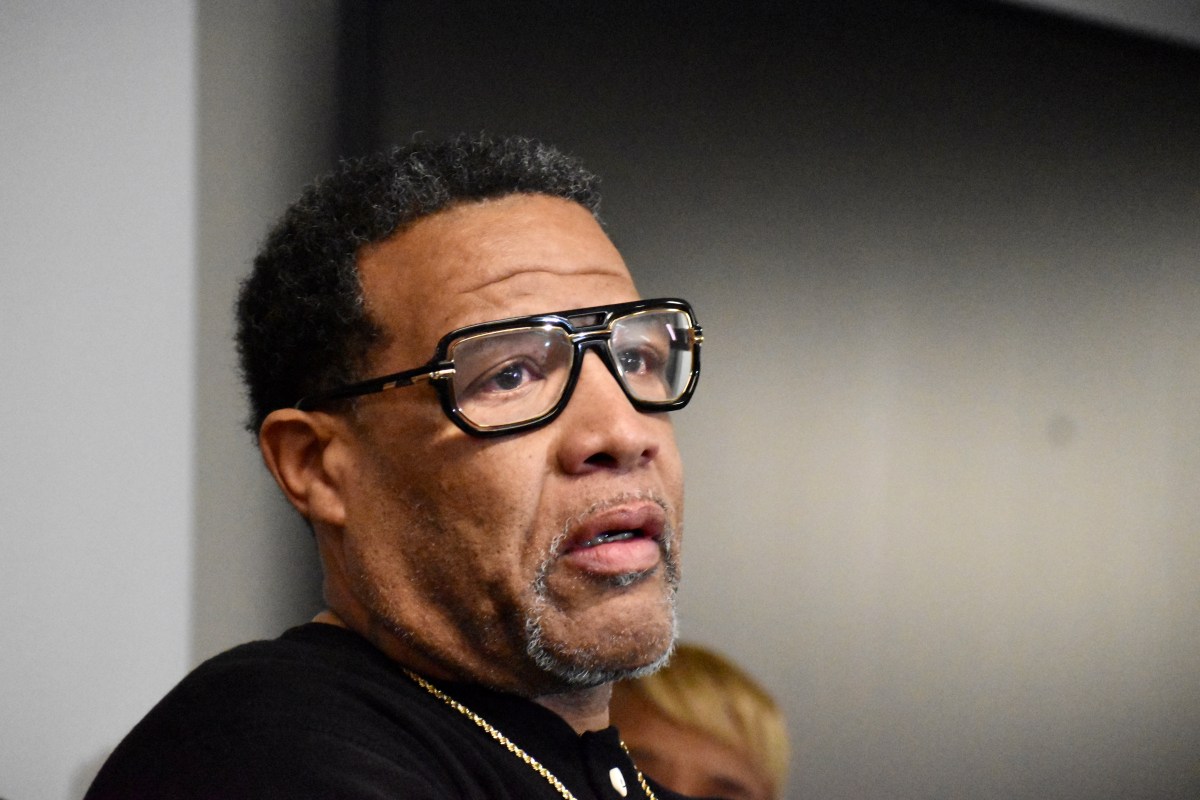

“People think that the funding comes entirely from the donations pinned to the saint,” says Paul D’Amore, feast committee member and owner/chef of North End restaurant Massamino’s. “Now it mostly comes from sponsors.”

Vetting sponsors is a year round process. Though the board is tight lipped about which ones fail to make the cut, they’ll reject offers from companies who fail to hold their business to saintly ethical standards. Turning down money is a big deal – not just for the feast’s budget but for a substantial amount of charity work. The society donates to causes as large as the Wounded Warrior Project to ones as small as buying coats for local families in need.

It isn’t just about money; the society also faces immense logistical challenges. Each January, the society coordinates with the city services on permitting and money. The 100 pounds of confetti that rains onto the parade needs to be purchased; it doesn’t (ahem) just fall from the sky.

In more innocent times, the confetti was more spontaneous – North Enders shred newspapers to throw off rooftops. These days, the Society needs to use confetti cannons. Trustee Jason Aluia blames recycling initiatives for homemade confetti’s decline. North End residents no longer keep enough newspaper lying around.

As the event nears, food venders and restaurants begin to prepare. D’Amore estimates that his business will pick up 25% during the feast. For local restaurants, that number is almost entirely North End faces they already recognize, many of whom are returning from out of state. Tourists stick to the streets and many North Enders start there, but, as D’Amore says “How many sausages can you eat?”

He means it rhetorically, but the answer to “How much street food can the city eat during what is ostensibly a religious celebration?” is “an ungodly amount.” It takes five days for Slush King – part of the old guard of Boston street vendors – to manufacture enough slush to feed the hordes who will crowd Endicott Street. Mark Nolan, the titular king, will load it onto carts he only uses for the North End feasts. Slush King’s wares have been gobbled at St. Anthony’s for nearly five decades, long enough to know he’ll sell between 250 and 300 gallons of the stuff.

St. Anthony’s feast has been a North End institution since Italian immigrants started it in 1919. The people who put on the festival have been continuously preparing for the next one nearly as long. The North End has changed, the feast has changed, but one thing will always be the same: The run on Pepto Bismol the week after is worth it.