By Jarrett Renshaw

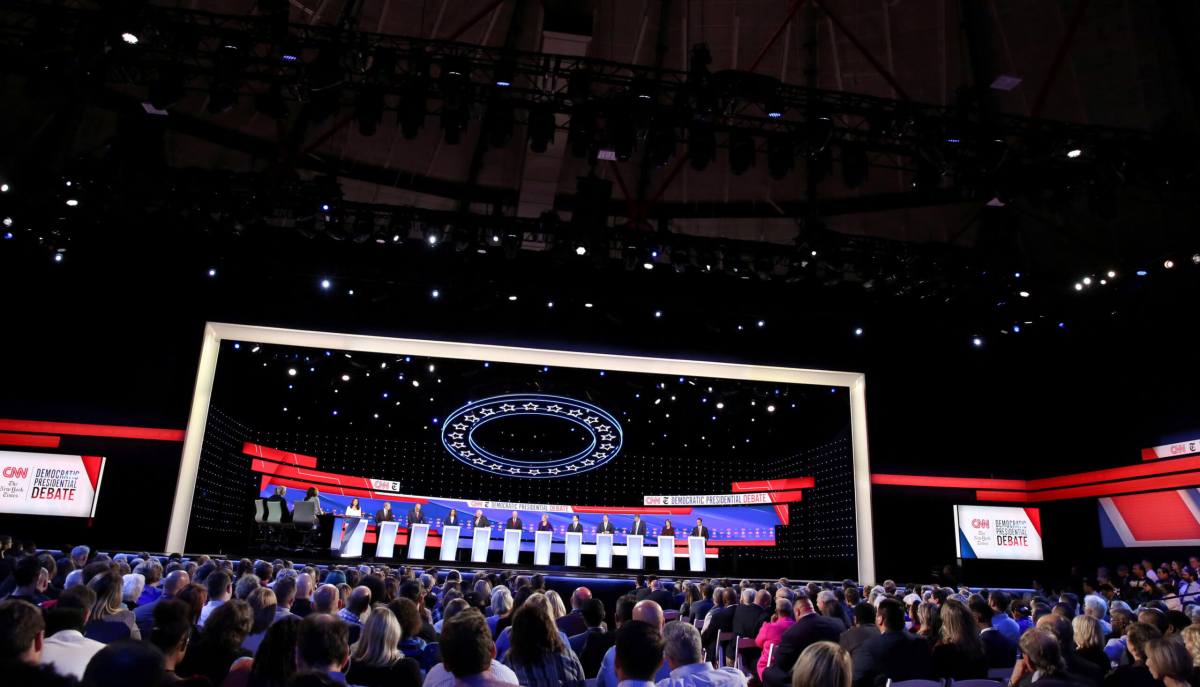

NEW YORK (Reuters) – The Democratic Party will officially nominate a 2020 presidential candidate at its convention next July, but not before a long primary season that kicks off with the Iowa caucuses in February and ends with the Puerto Rican primary in June.

The goal for candidates: Amass on a state-by-state basis the 1,885 delegates needed to be nominated on the first ballot at the convention in Milwaukee. A candidate must get at least 15% of the vote statewide or in an individual congressional district to be awarded delegates.

The nominating contest will be much different this time around after Democrats made changes aimed at increasing participation and ensuring transparency. Here are some key changes explained.

For a graphic on the delegate race, see: https://tmsnrt.rs/37bDD2f

FEWER CAUCUSES

In 2020, Democrats will hold caucuses in Iowa, Nevada, North Dakota and Wyoming, far fewer than the 18 conducted in states and territories in the 2016 campaign.

Caucuses require voters to attend a meeting for several hours and vote in the open by raising their hand or gathering with fellow supporters. The process has been criticized as undemocratic because it can dampen participation and is subject to intimidation.

The caucus system favors candidates with a strong, active base instead of broader support. U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, for example, significantly outperformed his rival, Hillary Clinton, in caucuses in the 2016 campaign.

The remaining states will hold primaries this cycle. In primaries, voters show up to their polling place and check the box for the candidate of their choice.

CALIFORNIA TO PLAY A BIGGER ROLE?

Traditionally, candidates focused on Iowa and New Hampshire in the early parts of the campaign season, hoping a victory in either of those two states – or both – would jumpstart their campaign and clear the field.

But California has moved its 2020 primary from early June to Super Tuesday on March 3. With Texas already on the Super Tuesday calendar, the switch means the nation’s two most populous states – both with large Hispanic populations – will vote on the same day.

Under mail-in voting provisions, California voters can begin casting their ballots on Feb. 3, the same day as Iowa’s first-in-the-nation caucuses. Texas voters can begin voting, under new rules meant to increase access, on Feb. 18.

Early voting and a reshuffling of the primary calendar will diminish the power of tiny and homogeneous early states in favor of much larger and more diverse battlefields. Now, candidates will need to spend more money on political advertising and make more trips to big-ticket states.

As a result, campaigns with deeper resources have begun organizing operations in California much sooner than normal.

WHEN CAN WE EXPECT A CLEAR FRONT-RUNNER?

In past elections, success in Iowa and New Hampshire was a good predictor of success in the primary. Conversely, a poor showing in those states forced candidates to bow out of the campaign.

But maybe not in 2020.

The large field of candidates combined with the new front-loaded calendar means more candidates are likely to hang around – if they can afford it – at least until March 3, when California and Texas weigh in on Super Tuesday.

Six of the 16 most-populous states will be among the nine to hold primaries on Super Tuesday, meaning nearly 30% of the U.S. population will have a chance to get in on picking the presidential candidates. By the end of March, elections covering well over 50% of the party’s delegates will have taken place.

The large pool of candidates could also mean the primary stays competitive into the early summer, potentially forcing a contested convention.

WHAT ABOUT SUPERDELEGATES?

Superdelegates are elected Democratic officeholders who are part of each state’s delegation but are not committed to vote based on the outcome of the state’s nominating contest. All Democratic members of Congress and state governors are superdelegates.

In 2016, many superdelegates announced early support for Clinton, drawing criticism that the party was tipping the scales in her favor.

Superdelegates haven’t been eliminated in 2020, but new rules limit their influence. This cycle, they will likely not vote on the first ballot at the convention.

To win on the first ballot, the front-runner must secure the majority of the party’s 3,768 pledged delegates available during the nominating contests leading up to the Democratic convention.

If the front-runner has fewer than 1,885 delegates, the convention will hold a second vote. On subsequent ballots, all delegates become unpledged and superdelegates can also vote.

Then, a majority of all 4,532 delegates will be needed to secure the nomination.

If a candidate wins a supermajority of pledged delegates – or about 2,267 – then superdelegates are permitted to vote on the first ballot.

(Reporting by Jarrett Renshaw; Editing by Colleen Jenkins and Nick Zieminski)