NEW YORK/LOS ANGELES (Reuters) – Anne Messman, a veteran emergency room physician in Detroit, knew something was wrong when she developed insomnia and became unusually irritated with people she loved.

She began experiencing persistent sleepless nights in late March, around the time seven COVID-19 patients died in a single nine-hour shift. But she did not think her insomnia was due to the dramatic one-day death toll. As an ER doctor, death was no stranger to her.

Perhaps, it was that the victims’ families had to be informed by phone because relatives are barred from hospitals fighting the highly infectious disease.

Perhaps, she thought, the sleeplessness was fueled by worries about her own safety. She takes medication that suppresses her immune system, putting her at higher risk from the coronavirus. Or maybe it was the possibility she could bring the virus home to her children, aged 8 and 9.

Then there were photographs in the media of bodies stacked in portable refrigerated storage units at Sinai Grace, the hospital where she works. Messman, 37, wondered if relatives of COVID-19 victims would see the photos of the body bags and worry that a loved one was piled on top of a stranger.

“I guess that to me was more disturbing than the death itself,” she said in a telephone interview.

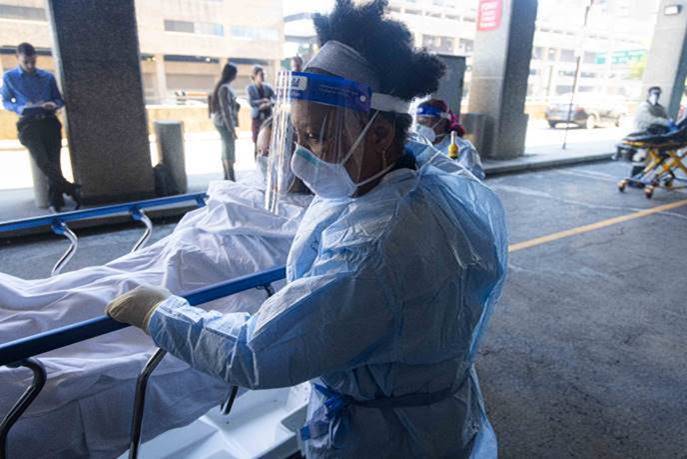

Messman and thousands of other healthcare workers across the United States are grappling with psychological traumas that mental health professionals say are more commonly associated with soldiers returning home from far-flung battlefields.

The unrelenting horror of COVID-19 has exacted a toll on healthcare workers who have seen patient after patient succumb to a disease that has killed more than 75,000 people in the United States alone in little more than two months.

Reuters interviewed eight doctors and eight nurses who said either they or their colleagues have been experiencing some combination of panic, anxiety, grief, numbness, irritability, insomnia and nightmares when they do sleep.

“Burnout, anxiety, depression, or irritability or moral injury, those can easily happen to anyone when you’re exposed to these kinds of circumstances for an extended period of time,” said Major Olli Toukolehto, a psychiatrist at the U.S. military’s 531st Hospital Center who has been deployed to New York.

Psychiatrists at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City predict between 25%-40% of frontline healthcare workers and first responders in the United States may suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of their involvement in the outbreak.

Messman loves to read but found she could not concentrate. Instead, she watched television or played with her smartphone “until my eyes were literally shutting against my will. But then I would wake up a couple hours later and just lay there.”

She says she is now getting better sleep, but is worried that her insomnia could recur if a second wave of the outbreak materializes later this year. Messman said she has been seeing a therapist with whom she has discussed her stress related to COVID-19.

`THIS IS A MARATHON UPHILL’

In hospitals in California, New York, North Carolina and elsewhere, support groups are filling up and calls to 24/7 help lines for employees are increasing. Some hospitals are deploying mental health experts to check on staff in the wards, or making group and individual therapy sessions available.

At Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, 70 one-to-one therapy sessions and 30 peer support group sessions were held last week, said Columbia psychiatrist Lou Baptista.

“It’s not surprising that people are fatigued … anxious, stressed and sad,” Baptista said. “This is a marathon uphill 110 degrees that you’ve never prepared for.”

In New York City, where more than 14,000 people are confirmed dead from COVID-19, including more than 20 healthcare workers, the public hospital system has partnered with the U.S. Department of Defense to provide resilience training for employees.

Toukolehto, who is involved in the collaboration, said one similarity between soldiers in war zones and hospital workers in the pandemic is the sense of constantly being under threat.

“In a combat zone you may be threatened by a sniper or indirect fire or rockets,” he said. “The COVID infection – that makes the healthcare employees here feel a similar kind of stress and anxiety that they indeed are in danger from an invisible enemy.”

Mount Sinai launched a new center last week to address PTSD and other mental health issues in its workforce. It has received about 10 calls per week through its 24/7 crisis hotline since that opened four weeks ago, said Sabina Lim, vice president and chief of strategy, Behavioral Health at Mount Sinai.

Some 20 employees across the hospital system have been referred for outpatient psychiatric evaluation so far, she said.

`A COLLECTIVE GUT PUNCH’

Death is familiar to healthcare professionals, but even veteran ER doctors could not have mentally prepared for the volume of dying coronavirus patients, healthcare workers told Reuters.

“I’m never going to be the same after going through this experience and I don’t believe anybody in healthcare in 2020 will be the same after this,” said Eric Wei, vice president and chief quality officer for NYC Health + Hospitals and an emergency room doctor in the New York City borough of Brooklyn.

The suicide of Lorna Breen, an emergency room physician at New York-Presbyterian Allen hospital, last month was “a collective gut punch” to all healthcare workers, Wei said. According to Breen’s family, she had suffered from COVID-19 and exhaustion from treating it as a doctor.

It may be too early to diagnose PTSD in front-line workers because these symptoms must persist for more than a month, Mount Sinai’s Lim said, but many are showing signs of acute stress disorder which can be a precursor.

Melissa, a nurse at an Indianapolis long-term care facility, recognizes her colleagues’ panic attacks during the COVID-19 pandemic as symptoms of mental trauma. She would know, having been diagnosed and treated for work-induced post-traumatic stress disorder four years ago.

The 48-year-old asked to use her first name because she is concerned about the stigma associated with recovering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Her colleagues are jittery and easily irritated, Melissa said. One described having heart palpitations on a recent shift. Another has taken disability leave from their facility, unable to work because of panic attacks and grief after losing several patients she loved.

Melissa’s facility serves around 150 patients, about half of whom have contracted the virus, she said.

“It’s like sitting waiting for a bomb to drop,” she said. “You don’t know if you’re going to live, you don’t know if you’re going to die.”

(Reporting by Gabriella Borter and Kristina Cooke, additional reporting by Joseph Ax, editing by Ross Colvin and Alistair Bell)