GROTTAFERRATA, Italy (Reuters) – (This November 30 story corrects in second paragraph to make clear order not founded by St. Basil and in eleventh paragraph, Italo-Greek rite, not Italo-Albanian)

In an ancient monastery behind huge medieval battlements in a hilltop town just south of Rome, 10 monks are striving to keep alive a 1,600-year-old spiritual tradition against increasing odds.

Aged between 23 and 89, they are among Italy’s last remaining Byzantine-rite monks. They are inspired by the teachings of fourth-century St. Basil, following an ascetic regimen of prayer and work.

Brother Claudio Corsaro, 27, abandoned a promising career as an opera singer to become a monk. The only singing he does now is in the chapel.

“I was only six years old when I felt the Lord for the first time but I fully realised my vocation many years later, when I had already started my singing career,” he said while walking between olive trees in the monastery compound.

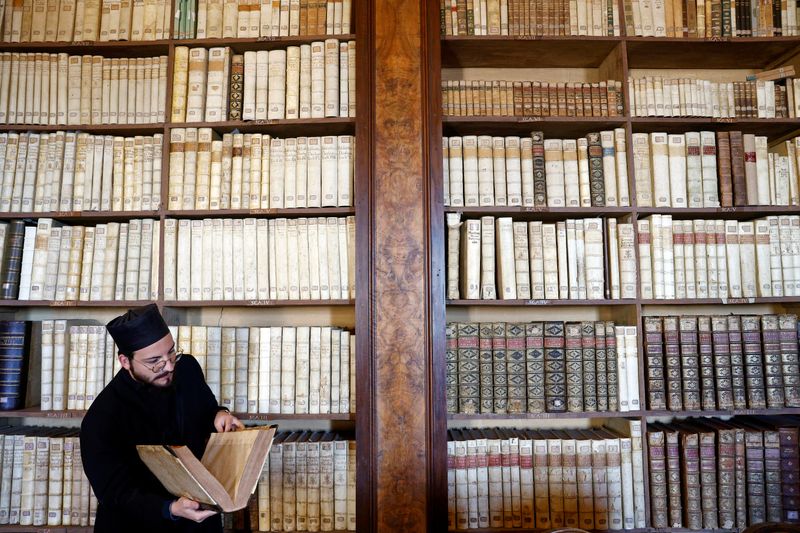

Corsaro and his confreres dress in the habit of Orthodox churchmen, including flowing black robes and the traditional flat-topped round hat.

Basilian monk St Nilus founded the Grottaferrata abbey in 1004, 50 years before the Great Schism of 1054 split Eastern and Western Christianity.

At the time, the Grottaferrata monks chose to remain faithful to the pope in Rome rather than switch allegiance to the newly established Orthodox patriarch in Constantinople, now Istanbul.

However, to this day they worship in the Eastern, Byzantine rite, including saying the Divine Liturgy, their version of the Mass, in ancient Greek. Catholics in the West say the Mass in local languages and occasionally in Latin.

The daily regimen starts at 5:30 a.m. with individual prayer and communal worship. Then there is work in the vegetable garden and olive groves, painting icons, study, and house chores. Lunch is followed by rest, vespers, more work, more prayer and then early to bed.

Most of the monks have connections to tiny ethnic Greek or Albanian communities in southern Italy populated by descendants of early settlers from the East.

They are the last monks of the Catholic Byzantine Italo-Greek rite.

Brother Filippo Pecoraro, 23, was raised in an Italo-Albanian family in Sicily and is from the Arbereshe people who fled Ottoman invasions of the Balkans between the 14th and 18th centuries.

“I grew up in an environment very close to the Church and this life choice was inside me,” Pecoraro said.

The young blood has not stopped the order’s numbers from shrinking significantly. In the middle of the last century the abbey was home to around 80 monks.

Nonetheless, Corsaro is steadfast in his belief that preserving the ancient tradition is his sacred calling.

“I feel like someone the Lord has chosen among the few to continue this responsibility and I thank God for the grace he has given me to carry out this task,” he said.

(Philip Pullella reported from Rome; Editing by Raissa Kasolowsky)