SIHANOUKVILLE, Cambodia (Reuters) – When casino owner Kang Qiang looks out the window of his 20th floor office in this city on the remote Cambodian coast, he sees construction cranes sitting idle.

The Chinese-funded gambling enclave of Sihanoukville has suffered a double blow. Travel restrictions imposed in recent weeks to slow the global coronavirus pandemic have deepened the effects of a ban last year on lucrative online gambling.

But Kang is betting on a future beyond the pandemic, banking on the return of money from China to finish transforming the scrappy frontier town into a gleaming metropolis.

In a sign of his confidence, Kang’s casino has installed gold urinals.

“This city is just starting, there is a lot of potential,” says Kang, 60. “I love it. Sihanoukville gives you a feeling of freedom and no control.”

For Kang and others, the city is like the China of several decades ago – with all of the promise and none of the competition. The current idle is only a blip.

“China is huge, there will always be people interested in Sihanoukville,” says Yin Hongsi, a 30-year-old from Chengdu who hires workers for one of the casinos. “You don’t need to worry if the Chinese will come back.”

The boom town on the Cambodian coast has a deep water port and is part of China’s Belt and Road initiative. In the next three years, Sihanoukville will also host both the Southeast Asian Games and a meeting of regional leaders.

As Chinese money has swept across Southeast Asia, Cambodia has become one of the most visible examples of the investment, with authoritarian Prime Minister Hun Sen doing all he can to strengthen ties to Beijing.

CASINO RUSH

In Sihanoukville, most of the money has been private, and the biggest share has gone into some 70 casinos – all of which are being ordered to shut from April 1 as a temporary measure to help slow the spread of coronavirus.

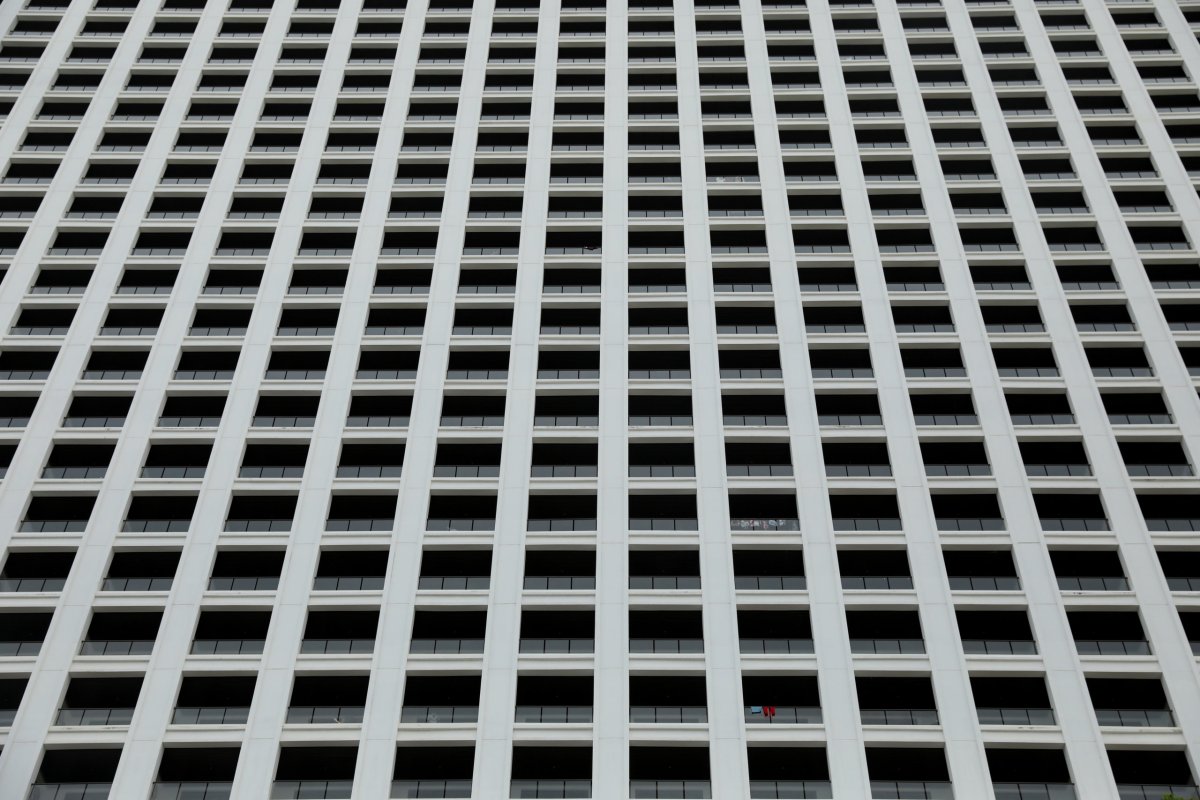

The casinos have reshaped the city’s landscape so frequently that locals struggle to recognize it.

The contrasts can be jarring.

Inside casinos, wads of U.S. hundred-dollar bills pile up in batches of $10,000 beside white marble ashtrays.

Outside, streets are coated in fine orange dust and pedestrians cross rivulets of sewage on scraps of plywood. It’s a disconnect familiar to anyone who lives on China’s margins.

“China speed”, exclaims Gavin Gao, a gleeful young Chinese tech entrepreneur from Chengdu who has chosen to stick things out.

“Sihanoukville is going at China speed … Here is China 2.0!”

Cambodians have mixed feelings about the Chinese. Their arrival brought money and jobs – and now their sudden absence is causing problems.

“People used to say ‘Sihanoukville is the best’. There are lots of Chinese and lots of money,'” says Siv Tia, a 69-year-old who makes a few dollars a day selling drinks in the market. “Now they say ‘everyone in Sihanoukville has a big bank loan'”.

The collapse of a half-built Chinese-owned building last year, killing dozens, fueled resentment in the town. So did the constant noise of construction, rising crime and rubbish piled in the streets.

“The growth was just phenomenal, too fast!” says Transport Minister Sun Chanthol. “Now things are slowing down so it’s a good opportunity for us to catch up.”

VIRUS FIGHT

The expatriates’ confidence is buoyed by China’s apparent success in fighting the coronavirus pandemic. As cases skyrocket elsewhere in the world, zero local transmissions have been reported on some days in China, where the virus originated.

“They got it under control,” says Bob Zhao, an earnest 28-year-old from Shandong who came to Sihanoukville seeking his fortune and found it as a sales consultant for a Chinese property developer.

“In China there are so many competitors. They’ve been to good schools, have good social experience. They are better than you. And the pay is low,” he says. “The opportunity here is better.”

Zhao sits in a window-lined atrium of a half a billion-dollar hotel, casino and apartment complex on the beachfront. It broke ground last August, just as the online gambling ban was announced, and has seen a sharp slowdown in sales because of the coronavirus, but is still on track to open in two years.

Zhao ticks off reasons Cambodia is appealing: it’s a U.S. dollar economy, Hun Sen is close to China and is a longtime, stable autocrat.

“Our money is safe,” he says.

Casino manager Yin has been making “at least double” what he would in China by working in Sihanoukville, but he acknowledges the flood of Chinese money has led to surging prices and the growing piles of rubbish.

Still, he says the Chinese money has sparked the economy in what he sees as a forgotten country.

“It seems like other countries are not interested in Cambodia, like America and Europe,” he says. “China is interested.”

Kang, the casino owner, is from Guangzhou, one of China’s biggest and most-developed cities. But he is convinced his future is on the dusty streets of Sihanoukville despite his casino losing money since November.

“Persistence means victory,” he says.

*Photo essay: https://reut.rs/3avL9X4

(Editing by Matthew Tostevin and Jane Wardell)