TOKYO (Reuters) – Japan expanded a state of emergency in the Tokyo area to seven more prefectures on Wednesday amid a steady rise in COVID-19 cases as a survey by public broadcaster NHK showed most people want to cancel or postpone the already delayed Summer Olympics.

The governors of Osaka, Kyoto and other hard-hit prefectures asked the government to announce the emergency, which gives local authorities the legal basis to curb movement and business.

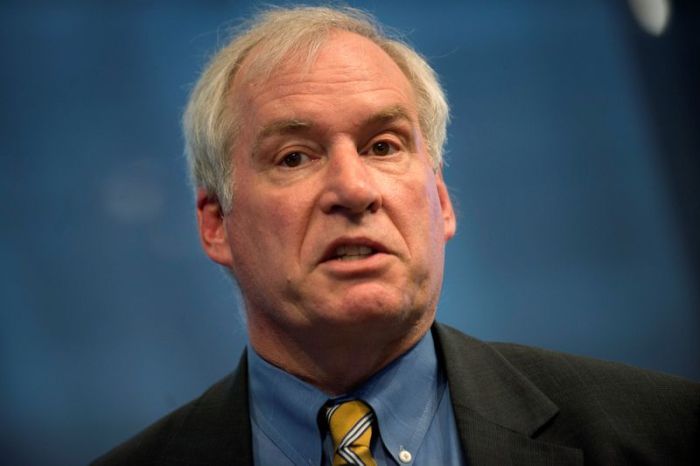

Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga has been wary about taking measures that would hamper economic activity, while he has put on a brave face against the mounting challenges of hosting the Olympics, delayed from 2020, in Tokyo.

“A declaration of a state of emergency is a powerful means, based on the law, for tackling the spread of infections, but it also places big restrictions on people’s lives,” Suga told a news conference.

“A very careful decision is therefore required of the government,” he said.

The prefectures to be added from Thursday are Osaka, Kyoto, Hyogo, Fukuoka, Aichi, Gifu and Tochigi.

As infections hover at record levels, opinion polls have shown a public increasingly opposed to holding the Summer Games. Japan’s coronavirus cases topped 300,000 on Wednesday while the death toll reached 4,187, NHK said.

In a weekend survey by NHK, just 16% of respondents said the Games should go ahead – down 11 percentage points from the previous poll last month – while a combined 77% thought they should be cancelled or postponed.

The Games are set for July 23 to Aug. 8.

Takeshi Niinami, CEO of beverage giant Suntory Holdings and an economic adviser to Suga, told Reuters he was unsure whether the Olympics could be held as planned.

The emergency declaration, covering 55% of Japan’s population of 126 million, is set to last through Feb. 7 and is much narrower in scope than the first one last spring. It focuses on combating transmission in bars and restaurants, while urging people to stay home.

Suga has been criticised for what many observers have said was a slow and confusing response to the pandemic. That is a sharp reversal from the strong support he enjoyed at the start of his tenure, when he was seen as a “man of the people” who could push through reforms.

Political analyst Atsuo Ito said he saw two major problems with Suga’s response to the pandemic: that it was incremental and slow, and that he was a poor communicator.

“He has almost no skill at messaging. Even at press conferences he’s looking down and reading notes. That doesn’t invite trust from citizens … The result is that his support ratings are falling,” Ito said.

An NHK poll showed that 88% of respondents think Feb. 7 is too early to lift the state of emergency – a view shared by many experts.

“It’s very unlikely we’ll see cases go down after just a month,” said Yoshihito Niki, an infectious disease specialist and professor at Showa University Hospital.

“Japan has been called a success story and there’s been discussion about the so-called Factor X – something that makes the Japanese more resistant to the virus – but that’s complete fantasy.”

(Reporting by Chang-Ran Kim, Elaine Lies, Kiyoshi Takenaka, Mari Saito, Takashi Umekawa, Tetsushi Kajimoto, Ritsuko Ando; Writing by Chang-Ran Kim; Editing by Giles Elgood, Simon Cameron-Moore and Nick Macfie)